Pushing Tin

Air traffic controllers are in the news again. The problem is not that they're drunk or dozing off. It's that we need more of them.

Billy Bob Thornton and John Cusack in the wonderful 1999 movie about air traffic controllers Pushing Tin. That movie was based on “Something’s Got to Give,” a 1996 NYT Magazine article by Darcy Frey on the insane pressures on air traffic controllers in New York, and the insane ways in which they coped. The Times news pages are presenting a similar view of today’s controllers.

The NYT leads the front page of its Sunday paper today with an expose of strain within the air traffic control system. Here is the tabloid-style headline in its online version:

The piece is part of a series the Times has run this year about close calls and mistakes in the US commercial aviation system. I wrote about one of the Times’s recent pieces here. I’ve done a long series about these close calls and the debate they have provoked in the aviation world.

Oversimplified, the debate is:

—Are stories like these inevitable results of the “law of large numbers,” which you’d find in any vast enterprise? Hospitals? Factories? Law enforcement or the military? At any given moment, some 10,000 commercial flights are in the air over North America. On a typical day, some 3 million passengers take off and land—safely—at US airports. The most recent passenger-fatality US airline crash was nearly 15 years ago. (By comparison: roughly 120 Americans die every day in car crashes, or five per hour.) Are these airline “close call” stories alarmist outliers?

—Or, by contrast, should we see these episodes as omens, warning signs, the equivalent of “iceberg ahead!” warnings as the Titanic steamed toward its doom? That’s a question I took up here. Here is my reader’s-guide to the latest Times story.

1) The most important part of this story: The numbers.

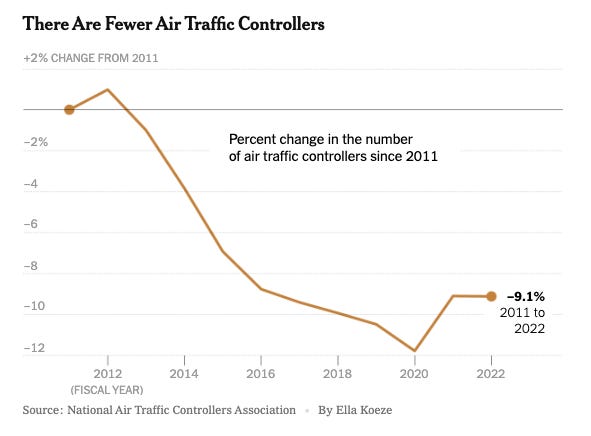

To me the news in today’s Times story was in this chart, about staffing levels at air traffic control centers:

There are lots of reasons for this pattern. The lumpy cycles of hiring-and-retirement ever since Ronald Reagan’s mass firing of all air traffic controllers forty years ago. Pandemic-era retirements in high-stress jobs everywhere. Blunt-instrument cuts in “big government spending,” without awareness of real-world effects. Take your pick.

But the real news of the story: It takes a certain number of people to run the system well. And the US now pays for fewer people on the job.

Infrastructure investment matters. On the ground. And in the air.

2) What I skip past: The atmospherics and dramatics.

For instance:

Elevator malfunctions forced employees to climb hundreds of stairs to reach the towers. Bees and biting flies harassed controllers who were directing traffic. Faulty air-conditioners left control rooms alternately broiling or freezing. One employee at a facility in Texas had to take in lightbulbs from home.

Please. If you have been to smaller airports, this is what they are like. They are legacies of decades-old US infrastructure—built in the mid-20th century, not adequately kept up since then. All these conditions should be better.

But I don’t think anyone who knows the system would seriously argue that this is the difference between US aviation at its safest and a system-under-strain now.

And as for reports on controllers being drunk or asleep on the job? Maybe. All I have to go on is 2000+ flying hours of talking with controllers over the airwaves. I’ve never heard any who sounded this way, but that could just be anecdotal.

Again, the point that matters is the staffing levels.

3) What the Times skips past: Pilots.

The entire focus of the latest Times article is on air traffic controllers.

The Times coverage is striking in underplaying the role of errors by pilots—hired by airlines or charter companies—rather than controllers, hired by the FAA or FAA contractors, in recent episodes.

For instance:

The most frightening recent US airline episode, as I described here, was early this year in Austin, Texas, when at FedEx flight was cleared to land on top of a Southwest plane waiting to depart. The Times went out of its way to name the Austin controller involved in that episode but has never named the Southwest airline crew that was arguably as responsible.1

Most of the recent close calls I’m aware of involve mistakes by corporate or airline pilots, rather than controllers. I am thinking of episodes in Houston, Boston, and New York.

Why does this difference matter? Airline pilots are generally protected by work rules that don’t apply to controllers. They have strict limits for on-duty hours, and mandated rest periods. They undergo more rigorous medical-test requirements. They’re not required to work overtime.

So, stress on controllers matter. But most of the errors I’m aware of are from pilots, and deserve comparable press attention.

Also: This story, by Ian Duncan in the WaPo, gives a lot of useful detail about the Austin situation not included in the NYT accounts.

4) What this means for passengers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Breaking the News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.