These Latest Air Travel Scares: What Do They Add Up To?

On the ground, in the air: More episodes that could have been much worse. Here's what we know so far about what went wrong, and how similar risks might be prevented.

Two days ago at Hobby Field in Houston: damage to a private jet that had just landed. Its tail was struck by the wingtip of another plane that was taking off, without authorization, on a crossing runway. If the departing airplane had left one or two seconds later, this might have been merely a frightening near-collision. If one or two seconds earlier, it could have been a fireball catastrophe. (Screenshot image from KHOU-TV in Houston.)

This post is about two recent high-profile air-safety episodes: What happened, what could have happened, what if anything might be learned.

1) Hobby Airport in Houston, October 24: One airplane hits another. It could have been much worse.

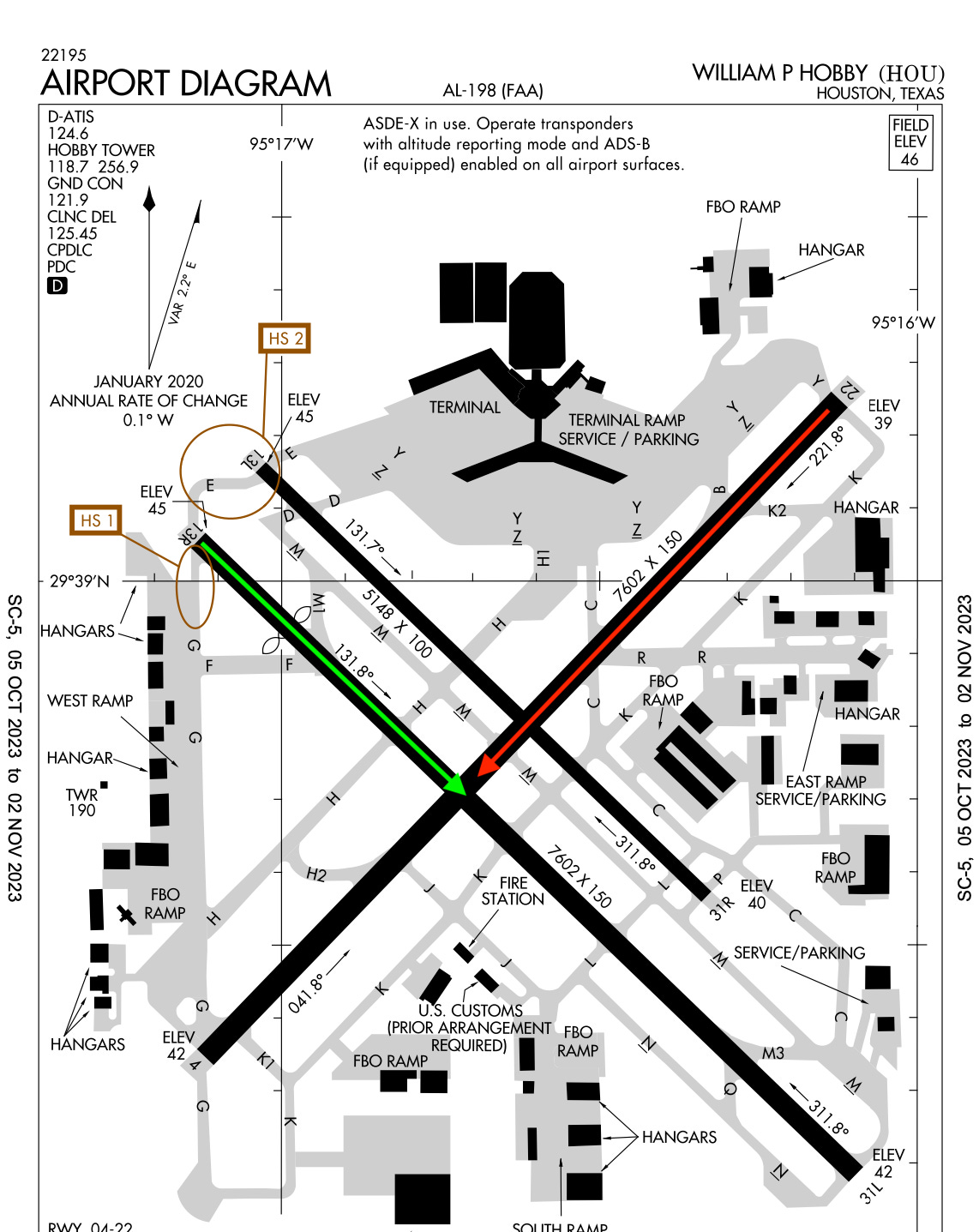

This is the official FAA diagram of Hobby airport, HOU. The annotations are by me, as explained below.

The green arrow, from northwest to southeast, is the path that planes landing this past Tuesday afternoon were taking. The control tower was sequencing and clearing them for approach and landing on Runway 13R (R for Right). Wind direction is more important on landing than on takeoff, so this would be the runway favored by the strong southeast wind at the time.

The damaged plane shown in the photo above, a Cessna Citation Mustang twin-engine business jet with tail number N510HM, was cleared for landing and had touched down before it slowed and rolled through the crossing of Runway 22.

The red arrow, from northeast to southwest, is the path that planes taking off on Runway 22 at HOU followed that afternoon. In this case it shows the path of the Hawker twin-engine business jet, N269AA. Where the green and red lines meet shows where the catastrophe almost occurred.

This computerized re-creation below from VASAviation—not an actual photo—gives the general idea. The lower plane, heading down to the right, is the Citation, just after landing. It is rolling through the right-angle runway intersection. The upper plane, heading down to the left, is the Hawker, accelerating for take off. In real life the two planes almost avoided colliding, but didn’t. At the crossing point, the Hawker’s left wingtip ran through the Citation’s tail. The results are the damage you see in the first photo.

From a recreation of the flight paths from a very instructive video by VASAviation.

If the Hawker had been two seconds slower in departure, the planes would have cleared. Two seconds faster, and it might have hit the other plane broadside.

Some natural questions:

-Why would airports use crossing runway paths anyway? To increase traffic flow. Planes waiting to take off from a busy airport can all queue for the departure runway. Then they can be cleared for takeoff, one by one, after each inbound plane has touched down on the arrival runway and passed the runway-intersection point. The very scarcest resource at busy airports is runway space for takeoffs and landings. This procedure allows airports to have several runways active at once, rather than splitting time on a single runway for arrivals and departures.1

-How can this be safe? Because everything about controller-and-pilot interactions is designed to provide a safety margin. The approach and tower controllers sequence the inbound planes to arrive at predictable intervals, with space for departures in between. The tower controllers instruct the outbound planes on when they can “line up and wait” on the departure runway, and when they are “cleared for takeoff” once the crossing traffic has cleared.

-What went wrong this time? Usually, everyone in the aviation world takes months or years to come to conclusions about perilous incidents. In this case, the NTSB announced the immediate cause of the problem within hours.

On Xitter and through other media, the NTSB said bluntly that the flight crew of the departing aircraft, the Hawker, had been at fault. According to NTSB, the tower controller had told them to “line up and wait” on runway 22. This is a formulaic phrase universally understood to mean: “Go onto the runway and be ready, but DO NOT take off.” It’s the equivalent of swimmers or runners hearing Take your mark. Set. And then waiting for Go!

According to the NTSB, the tower controller never told the Hawker crew “Cleared for takeoff,” the counterpart of Go! But they took off anyway.

-How and why could the Hawker crew have done so? I have not yet found tapes of the tower controllers giving pre-takeoff instructions to the Hawker and other airplanes. They will emerge, and perhaps they’ll explain how a professional flight crew could have made this most grievous mistake. Similar-sounding radio call signs for several airplanes? Overlapping and “blocked” transmissions on the radio? “Expectation bias” or “anticipation bias”—expecting to hear something, and thus imagining that you’ve heard it? Some other factor, from which future safety lessons might be gleaned?

In the meantime, everyone in the piloting world has already listened the post-collision ATC tapes, in which a Hawker pilot pompously blames tower controllers for leading his plane into “a mid-air.” You can hear that starting around time 0:40 of this VASAviation video. The controllers in this tape are, as always, unflappable in response. The cocksure pilot who scolds them has bad times ahead for him—assuming that NTSB is right that he and the other pilot in the Hawker cockpit were wholly in error when ramming into another plane.

-Has this happened before? This spring I wrote about a Learjet that had taken off, without a clearance, on a crossing runway in Boston, into the path of a descending JetBlue plane. That could have led to large-scale casualties. In the Houston case, a total of eight people were at risk aboard the two private jets.2

-Is this a ‘single point of failure’? Apparently so. The air-safety system has numerous fall-backs and safeguards. But—as with medical teams, law enforcement, military units, and many other groups—it can be vulnerable to professional flight crews that do not follow instructions.

Which leads us to…

2) Horizon Air, October 22: One pilot goes rogue. It could have been much worse.

This episode began seeming nightmarish, then became strange, and now is surpassingly bizarre, as well as having potentially been very dangerous.

In brief: an off-duty airline pilot was in the cockpit “jump seat,” behind the two on-duty pilots, on a Horizon Air flight last Sunday night from Paine Field, north of Seattle, to SFO. Such a jump-seat arrangement is perfectly normal. Flight crews rely on “deadhead” transport to get them back and forth between where they live and where their flying duties take them. If there’s room in the cabin, they’ll sit among the paying passengers. Otherwise, it’s a jump seat.

What was not normal was this pilot’s sudden attempt to shut off the airplane’s engines and take control of the cockpit.

Obviously he didn’t succeed. The two on-duty pilots subdued him; he went to the back of the plane and was handcuffed there; and on the plane’s diverted landing in Portland, Oregon, he was charged with 83 counts of attempted murder, for the 83 souls-on-board the airplane. He now says that he had been up for 40 hours straight and was in the grip of psychedelic mushrooms when he went amok.

I won’t give any more details here, because they are laid out so well, as usual, in this Blancolirio YouTube report. This is really worth watching—including the matter-of-fact discourse between the regular pilots and the controllers as the emergency was underway. Juan Browne of Blancolirio also goes into whether it really would have been possible to shut off the engines in a way the flight crew couldn’t reverse. (He says: Probably not.)

All that I’ll add is this brief clip of the exchange between Horizon pilots and a controller with a first report of what has occurred. Sang-froid all around:

I will say that this episode highlights two of the deep and ongoing challenges in air safety.