In the Air, on Thin Ice?

People in aviation spend a lot of time asking ‘What's the worst that could happen?’ in hopes that preparation can fend off the worst. It's a necessary question about the recent series of close calls.

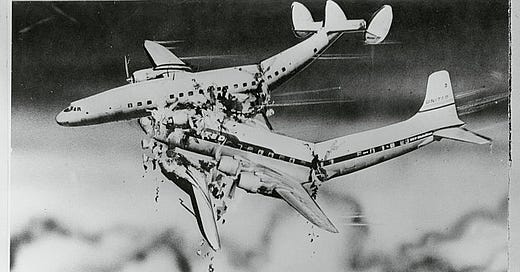

An artist’s conception of the disaster that fundamentally changed safety practices for U.S. aviation. In 1956, a United Airlines DC-7 hit a TWA Super Constellation in the skies over the Grand Canyon. Both planes plummeted into the canyon; all 128 people aboard them died. The disaster was a catalyst for safety-oriented technological upgrades and for legislative, regulatory, and corporate reforms. It would be better, of course, to have a catalyst without a catastrophe. (Getty Images.)

This post is prompted by yesterday’s big New York Times feature called “Airline Close Calls Happen Far More Frequently Than Previously Known.” I’ll set it up with a word about aviation risks more broadly:

People outside the aviation world can barely imagine how much time people inside that world spend thinking about crashes.

Most of your training as a pilot involves learning what to do when things go wrong. Much of the content of aviation magazines is about how things went tragically wrong for others. Getting new designs or technologies certified for aviation use can be glacially slow. That’s because the aviation authorities go through a glacial-paced sequence of “let’s imagine the worst” exercises. One of many hoary sayings in this culture is: There are old pilots, and bold pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots.

What is true of aviators who hope to survive is true of the aviation ecosystem as a whole. As I’ve argued many times, the co-dependent community of pilots and air crews, ground and maintenance staff, air traffic controllers, aircraft designers, weather experts, regulators, airline officials, and many others is remarkable in its ability to face and learn from mistakes.

I can’t think of an exact parallel in other fields or institutions. And today’s air-safety system in fact has no peer in its results. In the past thirteen years, through a total of well over 10 billion commercial passenger-journeys, exactly two people have been killed in U.S. airline accidents. Imagine if the medical system, law enforcement, road safety, schooling, and, yes, journalism operated at a similar standard.

An image of Star of the Seine, the TWA airliner that crashed into the Grand Canyon in 1956. It has the distinctive “salmon-shaped” fuselage and triple-tail of the Lockheed Super Constellation model. In that same era, a Constellation called Columbine II served as the very first Air Force One, carrying Dwight Eisenhower. (Wikimedia Commons.)

Bad breaks? Or a system that’s breaking?

The question yesterday’s NYT story raises is one I’ve discussed in a sequence of posts over the past two years. Namely, whether a string of frightening recent “close call” episodes for U.S. airliners amount to coincidental bad luck for a system that is still fundamentally robust. Or whether, to the contrary, they are signs of deeper strain in a system being pushed beyond safe limits—and toward a catastrophe whose details no one can predict but that will someday seem “inevitable” in tragic retrospect.

For specifics, please see the post about a near-catastrophe in Austin, this about a risky pilot mistake in Boston, this about errant pilots at JFK airport in New York, and this about an airliner that almost plunged into the sea when taking off from Maui.1

The latest Times story discusses these and other incidents and poses the question about system-wide safety this way. I’ve added emphasis for reasons I’ll explain in a minute:

They [the recent close calls] were part of an alarming pattern of safety lapses and near misses in the skies and on the runways of the United States, a Times investigation found. While there have been no major U.S. plane crashes in more than a decade, potentially dangerous incidents are occurring far more frequently than almost anyone realizes — a sign of what many insiders describe as a safety net under mounting stress.

This story was written by Sydney Ember and Emily Steel, with charts and flight-path graphics by Leanne Abraham, Eleanor Lutz, and Ella Koeze. It got prominent play on the NYT’s site yesterday and presumably will appear in print later on. Some of its features are optimized for online display, especially the animated recreations of how one airliner’s flight path nearly converged with another’s.

It’s a good and important story; please read it. But I hope you’ll read it with some extra context.

My guess about the story is that the team members producing it have dealt with aviation mainly as passengers. That is, not as pilots, air traffic controllers, former staffers of any companies or agencies involved, “hangar rats” at small airports, or other roles with first-hand exposure to the strengths and weaknesses of the system.

This is not a criticism. As reporters we spend most of our time asking other people to explain things we haven’t seen or done ourselves, so that we in turn can explain them to the reader. That is what makes the job so absorbing and fascinating.

But in this case I notice a few points in the story that I think would get different emphasis from many aviators. I mention them for your consideration in reading this story and others that are sure to follow on the air-safety theme. I’ll mention three.

A United DC-7 like the one that crashed into the TWA plane over the Grand Canyon. (Library of Congress.)

The real danger is on the runways.

-First, the paramount importance of runways in thinking about aviation dangers. Some passengers have nightmares about planes falling out of the sky. If they really want to worry, they should think about what happens on or near the ground.

At several points the Times story warns about “loss of separation” dangers when planes are “in the skies and on the runways,” as in the passage I quoted above. Obviously a collision in either realm is disastrous. But the latter danger is so much more pressing than the former that it should be discussed and thought of on its own.

There is all the difference in the world between a “close call” that happens on a runway, versus one in the open skies. A runway is a relatively tiny strip of pavement onto which planes that are taking off and landing must converge. A plane sitting on the runway can’t quickly move out of another plane’s way. It is no accident, so to speak, that the highest-fatality event in aviation history was a runway collision between two 747s nearly 50 years ago, in Tenerife.

By comparison, the sky is enormous. And even in the few places where it seems crowded, namely the approach lanes to major airports, there is vastly more room for a plane to maneuver quickly and avoid another plane’s path, and more robust systems to help them do so.

Dangers on or near the runway come in many varieties. One plane taxiing into a space where another has been cleared to land. One plane attempting to land before the plane in front of it has taken off. One plane preparing to take off, just as another plane taxis onto the runway across its path. An inbound flight crew mistaking a taxiway, where other planes are lined up waiting their turn to depart, for the runway—and heading toward a crash landing on top of them. Two planes being cleared to take off, or land, at the same time on runways that intersect. And all these come on top of the fundamental issue of assuring that the plane manages the last few feet of descent toward the Earth’s surface as safely as possible.

Every illustration I mention above has actually happened in the past few years. So far, with no fatalities. But when you read about airline “loss of separation” or “incursions,” give most of your attention to runways.

A legacy of the Gipper.

-Second, the enduring role of Ronald Reagan.

The most important part of the Times story is documenting the sources of strain on air-traffic controllers, from reduced head-count to brutal schedules that keep them from getting proper sleep. This is the part of the story that I hope gets legislative and public notice. Significantly, nearly all of the most worrisome recent events appear to have arisen from “human error” of some sort. Not engine failures, not mechanical breakdowns, not IT outages, but a pilot or a controller being too rushed, strained, fatigued, or overtasked to give full attention to life-or-death duties.2 That’s the danger signal.

The story says this about overworked controllers:

The roots of the current staffing shortage date to the early 1980s, when the Reagan administration replaced thousands of controllers who were on strike.

Everyone in the aviation world knows what the sentence refers to. But this is a weirdly indirect way to describe it.

What people in the aviation world say about this moment is: When Reagan fired the controllers. Because that is what he did—and what he took credit for at the time, at the start of his administration. Ronald Reagan saw this as a Calvin Coolidge-like stand against unreasonable pressure from a public-sector union. You can read the whole back story here. He meant it as an important moment, and it was. For him, for unions, for the aviation culture.

Republican (as most pilots are) or Democrat, pilot or controller, young or old—I’ve never heard anyone in the aviation world say that the “Reagan administration” had “replaced” the striking controllers. He fired them, and it’s worth stating that fact clearly.

Living out loud.

-Third, more emphasis on how much we do know, as well as what we don’t.