Two days ago I wrote about the latest airline “close call.” It happened before dawn this past Saturday, in near zero-visibility conditions, at the Bergstrom Airport in Austin.

—A Boeing 767 flown by FedEx was cleared to land, on a “Cat III” approach that allows an airliner to touch down safely even if the pilots cannot see the runway. Meanwhile a Boeing 737 flown by Southwest was cleared to take off from that same runway, directly in the descending airplane’s path.

—It appears that quick action and situational awareness by the FedEx crew prevented a mass-casualty disaster.

I’m writing today to highlight two online assessments of the incident. The first one greatly clarifies what happened and how things went wrong. The second argues that this should be seen not as an isolated mishap but as a warning sign.

1) ‘Confirming we are cleared to land?’ Who said what at Austin.

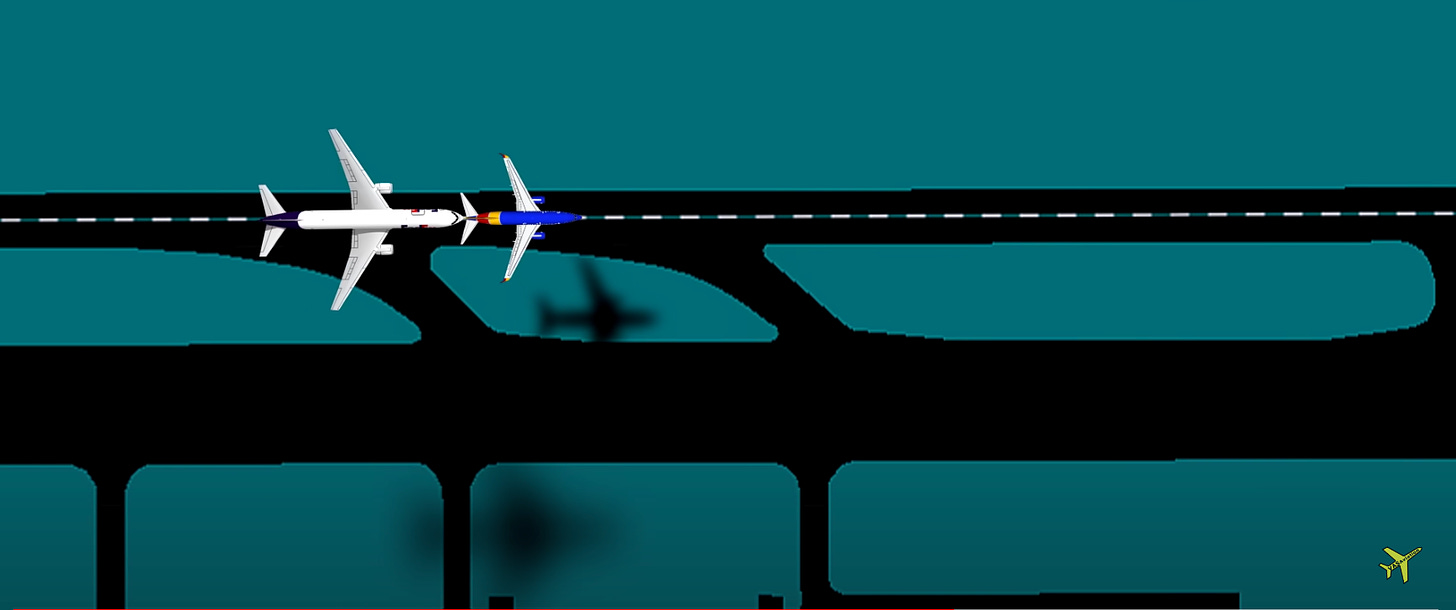

The aviation site VASAviation has a useful YouTube animation that matches radio transmissions with an approximation of where the two planes were. You can watch it on the embedded version above (used with permission) or at this link.

Here is a viewer’s guide to what you’re seeing and hearing. The three voices you’ll hear are:

Austin Tower, the controller clearing the planes to land and take off.

FedEx 1432 Heavy, the Boeing 767 getting ready to land.

Southwest 708, the Boeing 737 getting ready to take off.

Time 0:11, FedEx: The FedEx plane makes its inbound call. The crucial information it conveys is that it is on a “Cat III ILS” approach to Runway 18 Left in Austin.

Cat III is essentially an auto-land procedure. Precise signals from beacons on the runway guide the plane (via its autopilot) all the way down, even through fog so thick that pilots never see the ground.Time 0:20, Tower: The Austin controller clears the FedEx plane to land. He gives them “RVR” readings — Runway Visibility Range. They indicate that visibility is very poor.

Time 0:38, Southwest: Southwest announces that it is holding short of the same runway, and “we’re ready.” In aviation parlance this would mean: We’ve been through all the checklists and procedures, we’re all set to give it the gas and go.

Time 0:42, Tower: The controller reads the same RVR information to Southwest. This takes until time 0:56.

Then the controller says there’s a “heavy 767” three miles out for landing, and clears Southwest for takeoff.

I don’t know exact 767 approach speeds for this stage of flight, but it would cover 3 miles in hardly any time.

This transmission is sure to be the focus of attention. Why not add the familiar terms “cleared for immediate takeoff” or “cleared for takeoff, no delay”? (I have heard both of these phrases hundreds of times.) Why not tell Southwest “hold for landing traffic”, which I’ve also heard countless times? Why didn’t Southwest itself request a hold? Investigators will ask.Time 1:15, FedEx: The FedEx crew asks, “confirming we are cleared to land Runway 18 Left?” Meaning: “You know you’ve just put a plane in front of us, right?”

Time 1:20, Tower: Confirms FedEx is cleared to land, lets them know that a 737 will be departing “before your arrival.”

Time 1:54, Tower: “Southwest 708, confirm on the roll?” Note that this comes 34 seconds after the previous transmission, and nearly a minute after the tower cleared Southwest for takeoff.

In that minute, the FedEx plane has covered most of the distance to the airport. Presumably the visibility is so bad that the tower can’t even see the Southwest plane sitting on the runway. So the tower controller is asking: Hey, are you moving?

Southwest immediately replies, “rolling now.”

Investigators will also want to find out what the Southwest crew was doing through this time, in the minute after saying “we’re ready” and while knowing that another plane was about to land.Time 2:14, FedEx: “SOUTHWEST, ABORT!” This is the most unusual transmission in the series, because it involves one air crew (rather than the controllers) giving instructions to another.

Presumably at just this instant the FedEx crew has glimpsed the runway and seen the Southwest airliner directly ahead. On the chance that Southwest is not yet going fast enough for takeoff, FedEx is apparently hoping the other plane can slam on its brakes and stay on the runway. That way the Southwest plane would not fly up into their immediate path. FedEx is already beginning their “missed approach” climb away from danger.Time 2:21, FedEx: “FedEx is on the go.” This immediately follows the “abort!” call to Southwest. The FedEx crew is avoiding the collision by aborting their own landing. This message indicates that they are executing the standard “missed approach” procedures, starting with a rapid climb.

Up to this point the FedEx crew has taken total responsibility for the situation: asking about the danger with its earlier “confirming cleared to land” call; trying to warn Southwest once that plane came into view; immediately climbing away from the airport. At this point neither the tower nor Southwest has weighed in. It’s not clear that the tower controller has any idea where the Southwest plane is or what it is doing.Time 2:29, Tower: “Southwest 708, you can turn right when able.” The tower controller has heard the “abort” request; apparently he thinks that Southwest is still on the ground (and presumably he cannot see it); and he means for Southwest to get off the runway and turn onto a taxiway.

Southwest instantly replies “Negative.” Usually the aviation lingo would be “unable.” But aviation protocol also dictates this priority-list in emergencies: Aviate, navigate, communicate—in that order. Southwest is climbing out, and the planes are on a course to collide — though perhaps neither Southwest nor the controllers realize that. Niceties of terminology don’t matter.Time 2:50, Tower: Finally the controller starts giving the two planes instructions to keep them out of the other’s way. You can listen through the end of the tape. The FedEx crew is The Right Stuff-style unflappable the whole time.

What went awry here? That will be for investigators to work out. But based on current info, the group that did everything it could and more was that cockpit crew for FedEx. Admiration to them.

2. ‘Safety Systems Gone Wrong’

I’ve written countless times about the amazing safety record of modern U.S. airlines, about the redundant “what if?” protocols that keep problems from becoming disasters; about the relentless aviation-world commitment to learn from errors.

On his site “WWVB: What Would Vannevar Blog?”, a retired air traffic controller argues that these recent runway incursions are signs of deeper and more dangerous problems.

I encourage you to read the whole thing. But the gist is below. The “Tenerife” he refers to is the deadliest disaster in aviation history, when one 747 ran into another on a foggy runway.

This Austin situation is awful. As bad as it gets without body bags….

This was a total system failure. These airplanes were not separated by any good fortune of serendipitous timing. The only thing preventing another Tenerife was the FedEx crew's situational awareness and the breath of god.

American aviation is a system with different parts and priorities, checks and balances, and really quite a bit of public transparency. This system, like all systems, can be studied and improved. The people who study the American ATC system have been shouting for at least twenty years that the next major airplane disaster will look like a particular scenario.

It looks like this: Two big civilian jets. At least one of them is supposed to be using a runway for either takeoff or landing. The other plane will either cross the runway or try to use the runway itself, introducing the possibility of collision.

This is the nightmare scenario in American aviation, this is what the safety trend analysts will tell anybody who will listen, this is the thing that keeps people awake at night.

And this, of course, is what nearly happened recently, both in Austin and at JFK.

The world’s media were riveted through the weekend by the blundering Chinese spy balloon. What’s happening closer to the ground needs much more attention.

To my earlier post, "situational awareness" was a skill that was sacrosanct throughout my airline flying career. I'm skeptical that operational automation can ever replace that. So far in these reports, what I'm seeing is that the Fedex crew demonstrated it, to the benefit of all. Automation, in the form of the CAT-III autopilot autoland approach may have helped the Fedex crew's ability to assess their operational situation without the distraction of a hand-flown approach procedure in this case, which is far more attention intensive for both pilots. The 'go-around' call was a real time evaluation, its execution based on pilot-controller communications that automation would most likely not be aware of, and couldn't react to. But the Fedex pilots did. They figured it out in time.

Great post, Jim. Thank you for explaining so clearly how bad this almost was. And man, you're right about the Right Stuff thing. No shouting, no raised voices. Amazing.