State of the Union Part 1: How These Speeches Work

Different speakers, in different settings, 'succeed' or 'fail' in different ways. How to think about speakers, audiences, and messages.

Through many presidential administrations, I’ve done annotations in The Atlantic about each year’s State of the Union address. For instance, here’s one about a second-term SOTU from George W. Bush, referring back to his 2002 “axis of evil” speech, after 9/11 and when preparing the ground for the invasion of Iraq. And here is one from Barack Obama’s first term.

In this annual tradition, I did an Atlantic item several days ago on Joe Biden’s first official State of the Union address. Biden had previously spoken to joint meetings of Congress, but by tradition the SOTU count starts only when a president is beginning his second year in office, as Biden is now. You can read the whole original item here.

Now I’m doing an updated and adapted version of that dispatch, in two parts. The first—this post—is a set-up about speeches in general: What counts for eloquence, how a speaker can know the moment and the audience, why one person’s memorable language can sound forced or stagey from someone else.

The second item, Part 2 in today’s sequence, is an annotated version of Biden’s speech. For space I ended up cutting about half of the full speech text from the Atlantic version. I have restored some of it, and more comments, in the following Part 2 post.

Back to normal, as a good thing.

As an update for the introductory material below: Part of Joe Biden’s argument for himself—in this speech, and about his presidency as a whole—is back to normal, is better. I’ll note in the speech where Biden makes this point about the economy (which suffers from inflation, but has very strong job growth) and also about international crises (the U.S. is working with its long-time allies, and expanding its list of partners, rather than mocking or stiff-arming them).

It is remarkable to me how resistant the press is to mentioning restoration of normal function as an achievement. Two examples:

—For as long as I can remember, “crisis in the alliance!” stories have been a staple of foreign-affairs coverage. Name your post-World War II decade, and I can tell you about rifts between the U.S. and its usual partners in Western Europe or northeast Asia.1

In response to Ukraine, we are seeing accord among unusual-and-unexpected partners. (As Biden put it during his SOTU address, “Even Switzerland.”) Of course most of this is Vladimir Putin’s fault, and is to the credit of the leaders and people of Ukraine.

But it did not happen by accident. If friction within the alliance had more clearly emerged—as it is certain to, as the costs and carnage increase—you know that would already have seen front-page stories and TV panels on “Alliance in Disarray.”

A story that would make sense now is the reverse: An alliance has held together, and even expanded. How did it happen? How did Biden, Harris, Blinken, Yellen, Milley, et al manage this much coherence, despite such potentially divisive stakes? These stories are at least as consequential as “alliance in crisis” tales. But if they exist, they haven’t gotten comparable play.

—The other illustration involves the economy. I won’t belabor this further, since I explained the issue in this previous post, and Dan Froomkin has done so again this weekend. In brief: worrisome inflation, and heartening job growth, are both part of the economic reality of the moment. But the dominant press narrative is that the only thing that matters, or is happening, is inflation—and “prices at the pump.” Froomkin’s case-in-point is a New York Times newsletter that refers several times to “inflation soaring,” Biden’s “domestic woes,” and “consumer prices rising at the fastest pace in 40 years,” yet does not even mention the record-fast recovery from pandemic job loss.

That is the framing Biden is trying to offset.

Here is what I wrote the day after the speech, about speeches in general.

A primer on speeches: why they work, why they don’t.

(What follows, with minor adjustments, is taken from an Atlantic post written the day after Joe Biden’s State of the Union speech.)

Listening to Joe Biden give his first official State of the Union address on Tuesday night, I thought: This is strong. It is clear; it’s the right message in the right language. It reflects the speaker in an honest way. And it also brings something new to this tired form.

But each of those judgments rests on assumptions about speeches in general and State of the Union addresses in particular. So let me lay out my reasoning and then get to the details of the speech.

What makes a speech ‘good’?

What makes a speech “good”? Or “effective”? Or viewed as “eloquent”? Or perhaps eventually as “memorable” or “historic”?

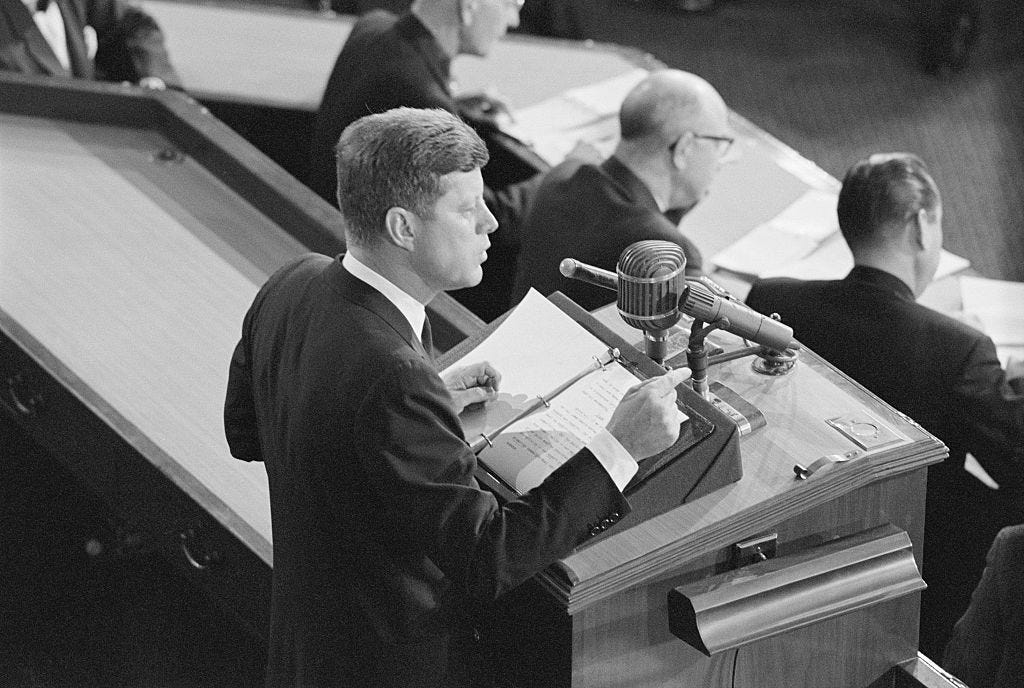

These are trickier assessments than they might seem, and can take time to settle in. The value and effect of a speech depend on some circumstances that a speaker can control, or at least be aware of: the message, the audience, the expected length of the speech, the expected tone, from jokey to statesmanlike. But they also depend on aspects of timing and fortune beyond anyone’s control. Winston Churchill’s “we shall fight on the beaches” pledge to Parliament in 1940 is remembered in a particular way because of how the next five years of combat turned out. As are Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “date which will live in infamy,” John F. Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner,” and Ronald Reagan’s “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

By contrast, George W. Bush’s “mission accomplished” declaration one month into the invasion of Iraq in 2003 is remembered in a different way, because of what happened afterward.

(I know how it feels to be involved in a statement that history has made look foolish. While working for Jimmy Carter in the White House, I was the writer on the trip where he gave a New Year’s Eve toast, in Tehran, to the shah of Iran as an “island of stability” in the turbulent sea of the Middle East. That was the official U.S. outlook at the time, which I did my best to express. Within little more than a year, the shah was out, and the Iranian revolution of Ayatollah Khomeini was under way.)

The different categories of speeches, and their different goals.

Some speeches are meant to excite or inspire. Political-rally speeches are in this category, the more so the closer they come to Election Day. Speeches to inspire the whole nation should obviously not be partisan. For instance, JFK in 1962: “We choose to go to the moon … not because [it is] easy, but because [it is] hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skill.” Speeches to energize the base can be partisan as hell, because voters are about to choose one side or the other. For instance, FDR just before Election Day in 1936: “[My opponents] are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

Some speeches are meant to console or commemorate. Robert F . Kennedy’s most moving speech may have been his unscripted statement of grief and resolve, at a street corner rally before a largely Black crowd in Indianapolis, when sharing the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had just been assassinated, in April 1968. This was two months before Kennedy himself was shot dead. Ronald Reagan gave his State of the Union address in 1986 a few days after the space shuttle Challenger exploded, and he began with a tribute to the seven dead astronauts. I believe that Barack Obama’s most powerful address was his eulogy in 2015 for the slain parishioners at the Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Some speeches are meant to explain. The example all aspire to is FDR’s first Fireside Chat in 1933, on the reasons behind the banking crisis. (He began, “My friends, I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking.”)

Some speeches are meant to motivate, organize, and instruct in the short run. After the “Bloody Sunday” marches in Selma, Alabama, Lyndon B. Johnson gave his most powerful speech, in urging Congress to pass what became the Voting Rights Act of 1965: “There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem.”

Some speeches are meant for reflection and guidance in the long term. Lincoln’s second inaugural in 1865. Martin Luther King Jr. at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963. George Washington’s farewell address in 1796, and Dwight Eisenhower’s in 1961. The commencement address by George Marshall at Harvard in 1947, the Nobel Prize lecture by William Faulkner in 1950, the “Moral Equivalent of War” speech by William James at Stanford in 1906. Having told my embarrassing “island of stability” story, I’ll add that I think a different speech I was involved in, Jimmy Carter’s commencement address at Notre Dame in 1977, on the role of human rights in U.S. foreign policy, stands up well: “I understand fully the limits of moral suasion … But I also believe that it is a mistake to undervalue the power of words and of the ideas that words embody … In the life of the human spirit, words are action, much more so than many of us may realize who live in countries where freedom of expression is taken for granted.”

Some speeches are meant to get the speaker out of an immediate bind. Bill Clinton’s career is packed with examples, from the town meetings in New Hampshire that made him the “comeback kid” in 1992; to his State of the Union address in 1995 after his party had lost 54 House seats in the midterms, delivered with Newt Gingrich seated behind him as speaker; to his State of the Union in 1999, while being impeached. This last speech was about economics and domestic-reform measures and it did not mention his legal problems. After introductory formalities it began, “Tonight, I stand before you to report that America has created the longest peacetime economic expansion in our history”, and it never looked back.

Some speeches are meant to be enjoyed purely in the moment, like a play or concert. Some are meant to be reread or studied on the page. Some are dignified by quotations and fancy language. Some are best when plainspoken and spare. Some fall into categories even beyond the ones I’ve named.

Here is the point of this long setup. It is as hard to define a “good” or “bad” speech as a good or bad song. It all depends—on who the speaker is, what the circumstances are, and what is the register in which the speaker sounds most convincing and authentic. Let’s apply those standards to this speech.

What Biden was trying to do, and how he did it

The questions about a speech like this are: Does it sound natural to the speaker? (A speechwriter’s skill is not so much the ability to “write” as the ear for the way the speaker would like to put things.) Does it make use of the times and circumstances? And does it tell us anything new?

By those standards I thought Biden’s speech was a real success, and one that might have been underappreciated because of the plainness that was in fact its main virtue.

The language. Some speakers sound natural when uttering phrases that seem headed straight for the Famous Quote books. Churchill. FDR. John Kennedy. A handful of others.

But most people seem puffed-up and strained when reaching for a fancy phrase. They can sound like high-school actors, overemoting, “To be, or not to be.” Nearly all of us are better in the mode Harry Truman or Dwight Eisenhower brought to the presidency, at their best: eloquence through plainness.

Early in his career, Biden favored fancy speechmaking. In his maturity he has embraced, as he should, his simpler and authentic-sounding “listen, folks” style.

In this speech, as I’ll note in the next post, Biden sounded like himself, rather than like a person intent on Speaking for the Ages. Even his cadence showed it. He gave the whole speech at a rapid clip, even when this meant talking over applause lines. Perhaps in part this was to deal with the lifelong stuttering challenge that John Hendrickson has so powerfully and beautifully described. But to me it came across as a person intent on delivering a message, rather than hoping to be admired while delivering it.

The fit-and-finish details of the speech also suggested a man on a mission. State of the Union addresses are notorious for their unsubtle, groaning-hinges transitions. “Turning now to affairs overseas,” or “We cannot be strong abroad unless we are strong at home.” The transitions in this speech are notable for not existing. Biden just made a point, then made the next one.

The substance. Joe Biden sat through dozens of State of the Union addresses as a senator, and sat on-camera through eight of them as vice president. Everything about this ritual is familiar to him.

So were the three main topics of his discourse: dealing with the Ukraine emergency, dealing with the economy, and dealing with the pandemic. Coordinating with other countries was part of his experience on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and as vice president, and comes naturally to his dealmaking nature. Ordinary-American economic issues were part of his identity as Scranton Joe. And the pandemic was the emergency he inherited on arrival. His treatment of them sounded like a briefing from a person in the middle of running multiple response teams, conveying which emergencies they were dealing with on which fronts. I’m always thinking of aviation-world analogies, and this reminded me of an experienced controller giving a rundown on where a skyful of airplanes were headed, and what his team needed to focus on next.

The backstage view. Being president is impossible. John Dickerson made the case in this cover story four years ago. I have written about it as well. To “succeed” in the job, a person needs a broader range of skills than any real human being has ever possessed. Public eloquence. Private persuasive power. IQ. EQ. Stamina. Luck. A generous imagination, but also cold-bloodedness. A thousand traits more. The question is not whether any president will “fail.” It is in which particular way, and how the world will judge the over/under.

Joe Biden was not explicitly making the case for himself, in handling the complexities of his role. (Although of course every speech, by every president, is implicitly an advertisement for the incumbent’s fitness.) But having heard nearly as many of these State of the Union speeches as Biden himself has, I thought this one amounted to a look at what a president’s job is. State of the Union speeches have rightly been mocked, including by me, as to-do lists. To me, this speech came across as a realistic view into the to-do urgency that makes up a president’s day.

That’s the perspective on speeches-in-general. Next in the queue: how these principles applied line-by-line in Biden’s address.

The U.S. under Dwight Eisenhower and the U.K. under Anthony Eden had a major disagreement over the Suez crisis in the 1950s. In the 1960s Charles deGaulle took France out of NATO. Through the later 1960s and into the 1970s there was the Vietnam War—and Richard Nixon’s surprise opening to China, and a nonstop series of trade and financial fights. In the 1980s Ronald Reagan military proposals allied him with Margaret Thatcher but touched off huge protests across continental Europe. That was a high point of strain for the alliance—until the Iraq War, when France and Germany led opposition to U.S. plans.

The stakes and details differ, but year by year you can find a “crisis in the alliance” theme.

This annual analysis by Jim is one thing I really enjoy about following his work