Journalism Needs to Engage With Its Critics

For the New York Times, that means a public editor.

This post started out several days ago as a follow-up to “A Word the Press Should Remember” two weeks ago, and “Framing the News” last week. Both of those discussed how the process of framing news coverage can make a bigger difference than more obvious issues of “balance” or “bias.”

I’ll lead with a few followup framing points, and end with a main theme that has become clearer just in the past day.

1. Where the term started: let’s hear from the linguists.

George Lakoff, whom I’ve known for years in the political realm and who has been a friend of my wife, Deb’s, for longer than that in linguistics, writes to point out more background on the term framing.

Lakoff himself wrote a seminal book on political framing nearly 20 years ago. That is Don't Think of an Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, which had an introduction by Howard Dean. Lakoff adds in his note:

The general theory of framing was invented by my late Berkeley colleague Charles Fillmore in 1975.

Thanks to George Lakoff for these updates, and for his guidance overall.

2. Framing in action: Covid test kits.

A friend who, like me, subscribes to The Washington Post writes to point out this recent headline:

My friend, who worked for many years as a Republican staffer, writes:

This is another media framing device that is more subtle than "Hillary's emails," but just as destructive.

Would a likely Republican president even have bothered with testing? And "shortchanges the most vulnerable" is a tiresome tautology that could by definition apply not only to any government program, but every aspect of social life. Because of problems with personal transportation, education, internet connectivity, and disposable cash, "the most vulnerable" are by definition shortchanged.

And “critics say” is a tiresome press cliché.

3. Framing by emphasis: America’s ‘bad economy.’

A typical mood-of-the-nation headline this past week read “Americans keep feeling worse about this high-inflation economy.”

Two elements make up the framing of this story: (1) that Americans think the economy is bad, and (2) that our current moment can be described as “this high-inflation economy.”

Inflation is a genuine problem, as any shopper knows. But it coincides with, and is connected to, the current record-strong American job market and fast recovery from pandemic-induced business collapse. As a reminder, only two years ago the headline on a university report read, “U.S. job losses due to Covid-19 highest since Great Depression.” For comparison, seven years after the beginning of the 2008 financial crash, the U.S. job market still had not fully recovered.

All these phenomena, good and bad—rapid inflation, rapid recovery, “staffing shortages” (bad for employers), tight job market (good for employees)—are parts of the same whole. Even the much-discussed “Great Resignation” indicates that more people have less fear about stepping away from immediate paychecks.

When news reports frame the moment’s contradictory combination as “this high-inflation economy”—as opposed to, say, “this high-growth economy,” which would be equally accurate—they invite reactions like the one shown in a new Quinnipiac University poll.

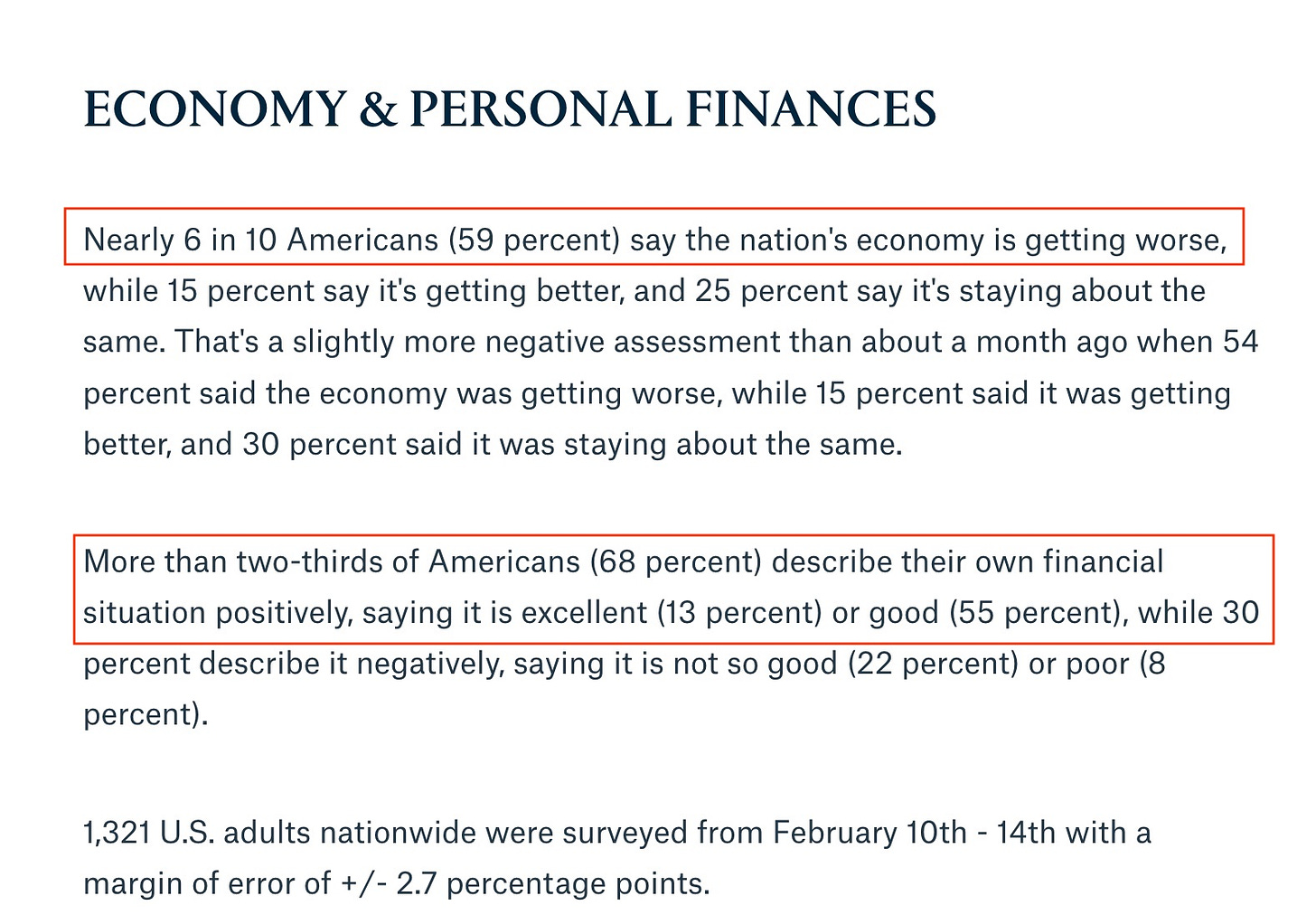

The poll found that a strong majority of Americans felt that the economy as they directly experienced it was good. Some 13% said that their own financial situation was “excellent,” and 55% said it was “good.” But an also-clear majority believed that the economy as a whole—the one they read or heard about, rather than experienced—was getting worse. From the poll, with emphasis added:

It’s a familiar pattern. For instance, as urban crime has gone down since the 1990s, fear of crime has gone up. For many years, polls have shown that Americans feel more optimistic about the communities they live in than about the country as a whole. This was a running theme in our book and HBO documentary film Our Towns.

Framing that suggests “things are worse than your own experience indicates” can usefully nudge people out of complacency. But it can also lead to a fatalistic sense that any localized progress is an outlier, and that public policies are all destined to fail.

4. Framing by omission: Amnesty International.

Last week the always-excellent Weekend Review section of the Wall Street Journal ran a long essay by the well-known Israeli historian Benny Morris, on why he thinks a new report from Amnesty International is wrong to classify Israel’s policies toward Palestinians as “apartheid.” Part of Benny Morris’s argument:

It’s true that some Israeli actions in the West Bank, such as travel restrictions, resemble apartheid. But racism is not what underlies the Israeli-Arab relationship, and occasionally the report displays some uneasy recognition on this score….

Instead, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is essentially national, a struggle between two nations over the same tract of land.

Morris’s article goes into much more detail, but the point for now is that he (and the WSJ) framed the Amnesty International report as important enough to merit a response.

The Washington Post has also run several pieces debating the pros and cons of the report. NPR had a story here. The AP noted it, as the PBS News Hour reported here. In the past few weeks the report has drawn major coverage throughout the world, including in most Western countries and in Israel.

Much of the U.S. coverage has been critical. For instance, soon after the report was released, the U.S. State Department’s spokesperson said the Department rejected its “apartheid” terminology. But the starting premise was that an AI report was something to be reckoned with.

A reader wrote in to note that one major news organization seems not to have mentioned the report’s existence: the New York Times. That claim appears to be accurate. I judge this based on searches just now of the NYT site, for stories mentioning “Amnesty International.” A number of them come up, but about reports on other areas of the world:

I am not equipped to assess the merits of the Amnesty report. I mention the difference in coverage for what it shows about framing. Most news organization chose to present the report as significant; many then disagreed with it. The most influential U.S. news organization chose not to mention it at all.

5. Framing in the Trump era: a defense that reveals the problem.

Here is the way the Gallup organization portrayed in a “Word Cloud” what the electorate had heard about the two main presidential candidates before voting in 2016:

People can debate forever what made “the” difference in bringing Donald Trump to the White House five years ago. It’s like the 2000 Bush-v-Gore results: No one will ever be able to prove why things ended up as they did. We know only how it turned out, and who wound up in control.

For the 2016 case, I will always contend that saturation coverage of “but her emails” was significant, mainly in dampening enthusiasm and turnout for Hillary Clinton—and encouraging an outlook of “what’s the difference, they’re all bad.” But, again, we’ll never know.

A week ago. one of the Washington Post’s best political writers, Philip Bump, made a brave stab at defending this difference in emphasis. It probably won’t come as a shock that I found his argument unconvincing, and far too forgiving of the press’s emphasis on the Clinton e-mail “scandal.” For instance, consider this portion of Bump’s piece, with emphasis added:

Two things made the situation worse for Clinton than it needed to be. One was that Clinton’s team at first treated the story dismissively, in a way that often antagonized reporters whose job it is to challenge those in power. The other was the way in which the material turned over from Clinton to the State Department was handled.

Nothing has emerged in the years since the story first broke to suggest that anything significant from Clinton’s private server that related to her work was not submitted to archivists. But the release of that material to the public in chunks meant that week after week there were new stories again bringing the issue to light. At times, those stories were not ones that merited elevating, but reporters, scrambling to be the first to find any document of significance, occasionally highlighted ones that had little….

Consider, too, that the initial story told us something new about Clinton: that this candidate running a campaign predicated on her experience had worked around governmental rules and constraints. Learning this about Trump is … not new.

The point about Trump’s excesses not being news, because they were … not new, is what I have previously called the “That’s Just Trump” framing line. Everyone knows he is going to ignore the rules and line his own pockets. Why bring it up again?

But here is why I respect Philip Bump for making his points, even as I disagree. At least he engaged. In framing terms, he presented criticisms of the e-mail coverage as something meriting a reply. In this he differs from much of the press corps that has shaped coverage in the Trump / Hillary Clinton / Biden eras.

5 1/2. Framing: the need for accountability.

Every person makes mistakes, and every institution does as well. The question is how we as individuals recognize and learn from our errors, and how institutions face harsh truths, or cover them up. I’ve often used the aviation world as an example. Half the contents of flying magazines are about crashes or near-catastrophes, framed as “what can we learn from this?” When an airliner goes down, the NTSB does a systematic, unsparing analysis of what went wrong—and the quality of these reports is one reason airline crashes in the U.S. have become so rare. (Back in 2020 I did an Atlantic article based on how the NTSB would assess the government’s pandemic response.)

For the mainstream U.S. press, one big institutional failure came in the run-up to the Iraq war, with credulous inflation of the WMD threat. But many news organizations later tried to reckon with what they had gotten wrong.

I contend that the mainstream framing of the 2016 election was another hugely consequential institutional failure. This included saturation coverage of Trump rallies starting in 2015, mainly for their spectacle value; and an obsessive emphasis on objectively minor failings by Hillary Clinton, epitomized by the notorious front page of the New York Times eleven days before people went to the polls.

Iraq and Trump/Clinton: Both similar in being errors in framing. Different in that news organizations did more to grapple with the lessons of the first mistake than the second.

A clear example has just come to hand. This weekend in The New Yorker, Clare Malone has an interview with Dean Baquet, who as Executive Editor has been in charge of the NYT’s framing and coverage through the Trump/HRC era.

In this interview Baquet does much less than Philip Bump did to reflect on how the press rendered reality:

He waves off, rather than engaging, any criticism of the Times’s presentation of the stakes in 2016. “I don’t have regrets about the Hillary Clinton e-mail stories,” he tells Malone. “It was a running news story.”

Imagine looking back on that front page, and on the Gallup word clouds, and saying, I don’t have regrets.He says that his only regret and error was not fully understanding the mood of Trump’s America, a course-correction that apparently led to the Times’s subsequent parade of “guy in a diner” stories.

He also waves off outside critics of the Times’s approach to politics: “I could care less about the unnuanced voices on Twitter.”

This last dismissal matters because it was on Baquet’s watch that the paper abolished its “Public Editor” position, claiming it was no longer necessary because social media would play that same role. As the Times’s publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, said in a memo announcing the change:

[T]oday, our followers on social media and our readers across the Internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be. Our responsibility is to empower all of those watchdogs, and to listen to them, rather than to channel their voice through a single office.

It’s a long road from “Empower all of those watchdogs, and listen to them,” to “I could care less.”

Power that will not explain itself is a problem. It’s true of surgeons, and police officers. It’s true of the people who fly airplanes, and who lead troops. It’s true of the Supreme Court, and it’s true of classroom teachers. It’s true in all walks of life.

The media in general are too influential and indispensable to wave off criticism. The New York Times in specific is too influential and indispensable to have its leaders or representatives sound so haughty.

For 14 years, the Times had a partial answer to this problem, by creating the Public Editor position. (That move itself, in 2003, was itself part of the Times’s reckoning with a previous coverage failure.) Some of the public editors were very good; some were not. But simply by their presence they represented the expectation that the paper’s leaders should engage, respond to, and explain serious questions about its coverage and framing. (For instance, as a current question rather than a provocation: Why has the Times decided not to cover this Amnesty International report?) Rather than wave questions off or say they “could care less.” Having a public editor did not solve all problems, but it was a step.

It is a step the paper should take again, when Baquet’s successor is named some time this year. (The paper has a mandatory retirement age for its “masthead” leadership.) It could be framed as a way for the paper to deepen its connection and trust with its ever-growing global audience. And that framing would be true.

Baquet’s interview...not an iota of willingness to examine his schema and its flawed terms, which are binary: good reporting has no point of view (what he dismisses as opinion), the truth he seeks is achieved by draining the story of anything but what he believes is some sort of factual purity that he thinks frames itself—of course the Times didn’t overhype and overheat the email story, it was a story, wasn’t it? So the 2016 campaign word cloud means nothing to him. Perhaps this blindness makes him Times executive editor material. Beg pardon for my cynicism, but Baquet’s sneering at the little people who dare to question his paper’s editorial decisions really got my goat. And the ghost of a smirk I so often see flash across journalists’ faces when anyone raises the subject of the public’s criticism of their work is empowered by Baquet’s.

I’ve heard comments by other journalists when they discuss their readers’ apparent hopelessness in offering criticism of their work. The consensus seems to be that we simply can’t understand what they do, and that they are of course doing the very best possible job. As you point out, it’s antithetical to the sort of self-examination that makes learning and improvement possible.

While there is quite a bit of space between you & Matt Taibbi, I read both of you for this reason: you offer a refreshingly bold and unsparing critique of today's major news organizations. The resounding message from both of you is the same: The Press/Democratic Party/Eastern Elites/Establishment Liberals just don't seem to get it. No matter how many losses, no matter how many Americans flip them the bird, their response is summed up by Baquet's "I could care less" or Clinton's "deplorables" remark. Even Obama was guilty at times: when asked if he cared about Fox's criticisms - given the fact it was the number one watched news channel in America - Obama almost rolled his eyes as he said, "I really don't." The result of this arrogance is this: no matter how overtly qualified, experienced, even egalitarian the candidate, voters are appalled at the arrogance and will vote no on that basis alone.

Same with media. NY Times may be the most influential news organization in the country right now, but there may be more Americans who refuse to read its articles than refuse to watch Fox "News." And that's probably the biggest reason America had to tolerate 4 years of the most incompetent, corrupt charlatan in our history.

Media holds power just as politicians do. And as it does with politicians, that power comes with responsibility as well as benefits. Those who shirk their responsibility to the truth and to their followers risk losing their positions, and deservedly so.