Return to Media World: More on Making the Sausage.

Some recent examples of "framing" and why it matters. Take heart! One of them is positive.

One week ago Amna Nawaz, of PBS NewsHour, confronted Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the president of Turkey, with serious and tough questions. He lost his cool. She kept hers, and provided a much-needed positive example of how journalists can deal with autocratic leaders of this era.

An ongoing theme in this space is the relationship among framing, transparency, and accountability in the news business. The latest installment, “Let Us See How the Sausage is Made,” was here, plus another here. As a reminder:

The news decisions that really matter involve framing: how a story is conceived, presented, and played. These are the messages conveyed not by an article’s contents but by its headline and subhead, the photos and graphics, the social-media “sells.” Because of limits on time and attention, for most stories the summary and packaging are all that most readers will ever see.

But these same framing decisions, which deliver so much of a story’s impact, are the parts of the news process least often revealed or explained. We can all see whose byline is on a story or whose voice is in a broadcast report. But we don’t know how the story got its headline, why it’s at the top of the page, what background and context it includes and leaves out.

Part of this is inevitable. Editors spend all day making judgment calls under time pressure. Naturally they get some calls wrong; even the right calls may be subjective and 51/49. People sitting at the editing desk don’t have time to explain what they’re doing, while they’re doing it.

But the newsroom is not the only place where judgment calls under time pressure make a big difference. Why did an emergency-room staff choose a certain treatment? Why did security guards act in a certain way? Why did pilots or air-traffic controllers order a “go-around”? And because no one likes being second-guessed, many institutions have built in regular channels for asking these uncomfortable “how and why” follow-up questions.

Crucially, getting a fuller explanation is different from enforcement. No sane person wants to impose formal review-and-approval boards on the free press. But explanatory systems can leave everyone better off. (Example from the aviation world below.1)

This was the whole idea behind “Public Editor” positions, of which the most prominent surviving example is Kelly McBride and her team with NPR. The special power of a public editor is authority to ask questions about the sausage-making: Why this headline? Why that photo? And to share the answers with the public. Every reporter within range of a keyboard has written at least one story on the virtues of “transparency” for other organizations. Public editors brought that same reasoning to our own business.

When the NYT mistakenly abolished its public editor position in 2017, its publisher also-mistakenly claimed that “our followers on social media and our readers across the internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog.” This claim was mistaken because Tweeted queries and critiques on Substack lack the in-house authority of a public editor’s explanations. In my own experience, they rarely get a response.

Nonetheless, here are a few more backstage questions of the type a public editor might ask. They start out with looking for “secrets of success.”

1) Factual preparation, temperamental control: Amna Nawaz and Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Last week PBS NewsHour aired a remarkable 12-minute interview by its co-host Amna Nawaz with Recep Tayyip Erdogan, president of Turkey. The main backstage question about this encounter is how the NewsHour staff prepared for it (and what others might learn), and how the on-air figure, Nawaz, managed the temperamental challenge of interviewing a self-important authoritarian.

The combination of preparation and temperament is what deserves study here. Political reporters in the US often mistake bluster for toughness. If they’re yelling out a “gotcha” question, that means they’re doing their job. When talking with Erdogan, Amna Nawaz was faultlessly low-key and polite,2 yet relentlessly on point.

As the interview went on, the autocratic Erdogan seemed more and more visibly miffed that a mere journalist—a foreigner, a woman—would dare challenge him to his face. At one point, after Nawaz apologized for incidentally speaking over him, he said, “Don’t interrupt. You have no right to interrupt. You are not going to interrupt me. And [you will] respect me.”

She didn’t flinch—or mug for the camera, or act as if this was mainly about her. She persisted, one might say.

I recommend watching the whole thing. But if you want to skip to a highlight, you can start around time 10:00 of the video. You’ll see why. We can learn from Nawaz and her NewsHour team.

2) ‘The Mess in Washington’: Presenting one party’s internal struggle as an institution’s collapse.

Over the past week, members of the small, extremist “Freedom Caucus” that is holding the House GOP hostage said they would welcome a government shutdown, rather than trying to avoid it.

If a shutdown happens, the reasons won’t be like those of other such events in recent decades. It won’t be Senate vs. House. Nor Democrats vs. Republicans. Nor Legislative vs. Executive. It will simply be one faction within the House GOP against another part. It’s a historic failure of one party’s coherence and control.

Yet one week ago, here is how our leading newspaper presented the situation:

The story casts the crisis as Congress’s failure, not one party’s. An institution was “faltering,” rather than being held hostage. It’s like a report on a raging fire, lamenting that destruction will continue until “a solution is found” between arsonists and the fire department.

It would be useful to know more about that framing. And it would be even more useful and interesting to know about the completely opposite framing of the situation on the Times’s front page today:

Before making this U-turn reversal (in two stories by the same reporter) did editors discuss and reject the previous framing? Did the reporter have more control over the second story’s presentation? Or less? Did something else change, to convert passive-sounding “falters” to active-voice “sows havoc”? Did they assume no one would notice?

It would be better for the Times, and everyone, to know, rather than having to guess.3

3) All that matters, is the politics.

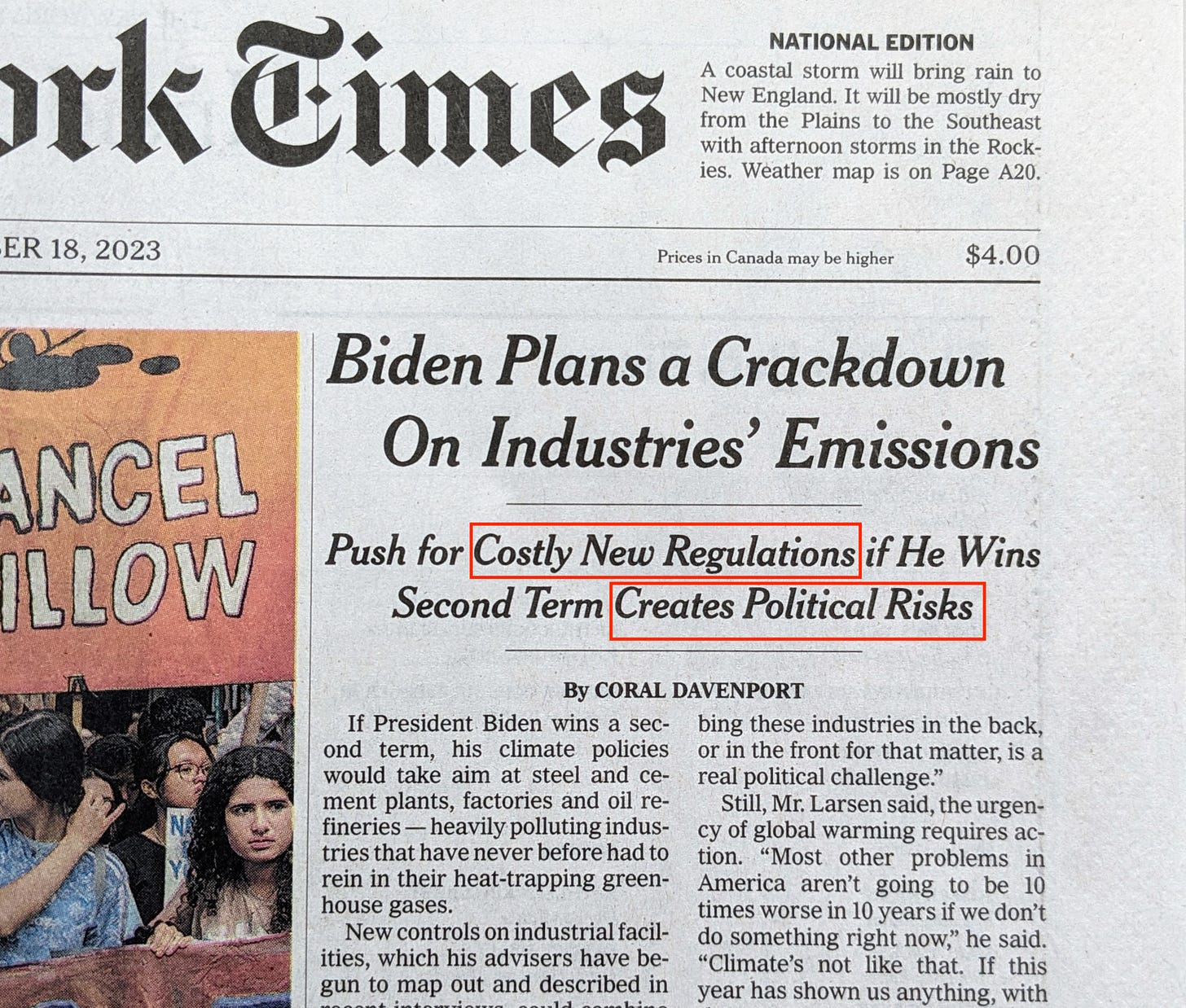

An incumbent president proposes a major climate initiative for his second term, if re-elected. Our leading paper puts it on the lead position on its front page, and frames it this way:

Yes, the costly new regulations and political risks are part of the story. But imagine if you were reading this account from any other part of the globe, or any time in the future. Imagine: “US pledges to take lead in dealing with heavy industries.” Or, from a politics-first perspective, “Nation’s oldest president makes bid for youthful support.”

Maybe the Times’s choice was “right,” maybe “wrong.” Either way it would be useful to know why. Especially given that this same story had an entirely different presentation in its online version:

Why the change? By whom, and in light of what factors? It could only help the Times’s credibility to disclose more.

4) All that matters, is the politics: WaPo Edition.

Here is yesterday’s headline from the Washington Post, on the departure of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

In 1973, Richard Nixon ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to fire the special prosecutor investigating Watergate, Archibald Cox. Richardson refused the order, and resigned. Nixon made the same demand of Richardson’s deputy, William Ruckelshaus. He too refused, and resigned. (Robert Bork finally carried out the order.) This was known as “the Saturday Night Massacre,” and sped Nixon’s demise.

I was reading the Washington Post back in those days, and do not recall headlines calling Richardson or Ruckelshaus “polarizing.” Or framing their stands as “admirers say / critics contend.”

Yet that is how the Post of this era decided to frame the departure of Milley, who had tried to insulate the military (and its nuclear weapons) from impetuous misuse by Trump. The Post headline appeared even after Trump ranted that Milley should face the death penalty for his “treasonous” disloyalty to Trump himself.

Why this framing? Would a Watergate-era Post have presented stories about Richardson et al this way? It’s the kind of judgment editors might usefully discuss.