More Airport Close Calls: This Is Getting Serious

The air travel system is under constant pressure to move more people, faster. The strains are mounting up.

Screenshot from RealATC animation of two airliners mistakenly vectored nearly into each other on departure from Los Angeles International Airport early this year. The sky is big, but the safety margins that have made airline travel so phenomenally safe may be eroding.

Want something to think about other than political, judicial, and media woes? How about aviation safety! In this post I’ll give you a look at the latest spate of “close calls” for US airlines—three of them just this month. As with previous installments on this topic, the big question when bad things nearly happen is: Coincidence? Or, instead, Warning?

-“Coincidence” boils down to the Law of Large Numbers. If US airlines operate 45,000 flights each day, inevitably some things will go wrong. But for more than 15 years now, ever since the Colgan crash in Buffalo that killed 50 people early in 2009, the multi-layer protections of the air-safety system have always kept mistakes and breakdowns from becoming disasters.

-“Warning” is the suspicion that surface cracks are signs of deeper fissures, and that close calls are mounting up too rapidly to ignore.

I still view commercial air travel as overall the safest way people can spend their time. But these latest episodes have moved me into the “warning” camp. The system has already come close to a big tragedy, last year in Austin, and has been spared others mostly by quick reflexes of flight crews or air traffic controllers, or by sheer luck.

What’s in common among these cases.

To illustrate each of these cases, I’m relying on explanatory videos produced by VASAviation, a YouTube channel run by a professional pilot named Victor, who is based in Spain.1 All these videos are short and very clear, but if you had to choose only one to listen to, I’d suggest the #2 incident, from DCA in Washington, because of its vocal drama.

Three of these close calls happened on runways rather than in the air. That’s not surprising: The most dangerous place a modern airliner can be is on the ground. (Why? In simplest terms, because so many huge aircraft are trying to use the same little strips of pavement at roughly the same time.) The highest-fatality accident in aviation history remains the Tenerife disaster of 1977, when a 747 roaring for takeoff smashed into another 747 sitting on the same runway. That’s the nightmare for everyone involved in airline safety.

You’ll also see that these recent close-calls all appear to involve mistakes or misjudgments by air traffic controllers, rather than flight crews. That seems unusual—we hear about “pilot error”2 all the time, but not “controller error.” I have long viewed air traffic controllers as setting a standard for the rest of us in competence and unflappability. But at the moment the controller corps is depleted, for many reasons, while the number of flights is again going up. This means more pressure on controllers, pilots, and all others operating with less rest and more strain. The system has still been lucky. But luck is not a plan.

Here we go with the short VASAviation videos, which again I encourage you to watch, followed by timestamped notes about what you’re seeing and hearing.

1) Kennedy Airport, New York, April 17, 2024.

Many big airports have sets of parallel runways, spaced far enough apart that both can be used at the same time. To maximize traffic flow and minimize traffic conflicts, controllers often use one of the parallel runways strictly for inbound planes, as they land, and the other strictly for departing planes, as they take off. Things can move faster that way.

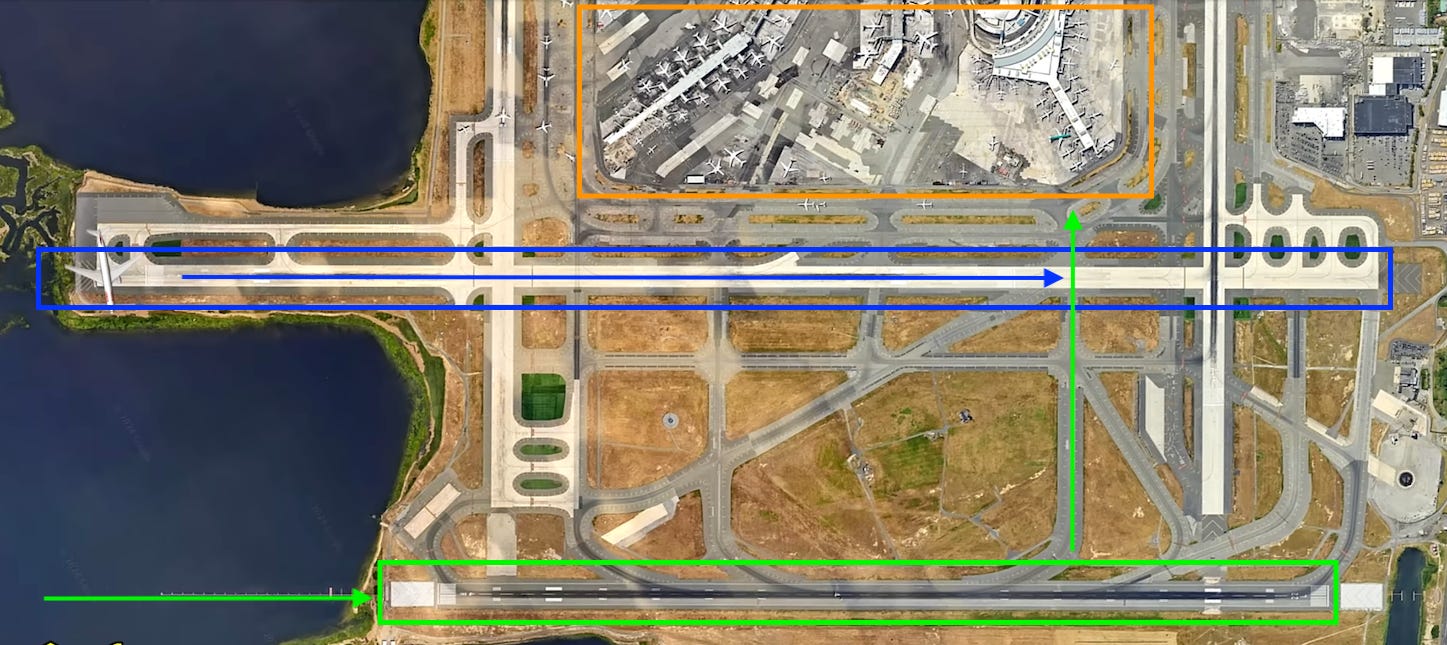

But given the layout of most airports, working with parallel runways naturally creates a ground-traffic challenge. Planes using the runway farther away from the terminal, whether for takeoff or landing, will normally need to cross the closer-in runway, which is also in use. The image below, from the VASAviation video on the recent Kennedy airport incident, shows how this works.

Screenshot of JFK Airport from VASAviation. Highlights by me.

In this image, planes landing at JFK would be traveling left-to-right toward touchdown on Runway 4 Right, highlighted with the green box. After landing, they would eventually need to taxi to the terminal (top of image, highlighted in orange). This would mean turning left along a path like that shown by the upward green arrow. But meanwhile, planes leaving JFK would be taking off on Runway 4 Left, along the path shown by the blue arrow.

As you’ll notice, the paths cross. Safely orchestrating this crossing-traffic ballet is up to the controllers. “Ground” controllers tell the planes where and when to taxi around the airport. “Tower” controllers tell them when to take off or land. “Cleared to land” and “cleared for take off” are the magic phrases pilots must hear from a tower controller, and that you can listen for in these videos. “Cross Runway XX” is the magic phrase from a ground controller, which a pilot must hear before crossing an active runway.

This part of the controller team’s role is more or less like stop lights and pedestrian Walk/Don’t Walk signals at a busy intersection. Everyone can get where they’re going safely, as long as they all obey the signals and take turns.

To keep things moving smoothly and safely, everyone involved in air safety is supposed to have a mental picture of what everyone else is doing. Controllers see on their radar scopes where planes are in the sky, and they look out of their towers to see planes on the ground. (Many airports have the equivalent of “ground radar” too, to track planes as they taxi.) Pilots listen to “the frequency” not just for their own instructions but also to hear what the other planes in the vicinity are doing, and where they have been told to go. Ground controllers work with tower controllers as they share responsibility for each plane.

Last week at Kennedy airport, this coordination and shared mental picture appears to have completely broken down. In simplest terms, some controller(s) had cleared four separate airliners to taxi across an active runway, at just the moment another controller had cleared an airliner to take off—directly toward those planes.

The cover image on the YouTube recreation gives you the idea, and the brief video takes you through the whole thing.

Time-stamped highlights from the video:

0:10 A controller tells a SwissAir flight, “Swiss 17k heavy,” to “line up and wait” on Runway 4 Left. That is, to be ready to depart. That’s the plane shown in green in the image above.

0:30 The beginning of a sequence of controllers clearing airplanes to cross this same Runway 4 Left. This continues for a while and eventually totals four planes, two of which are shown in blue above. Significantly, these instructions are coming on different radio frequencies than the one SwissAir is listening to.

0:40 The SwissAir flight is cleared for takeoff on this 4 Left.

1:05 The SwissAir crew starts rolling but then sees what is happening before the controllers do. It quickly “rejects” [aborts] the takeoff.

The next two minutes of the video are planes re-arranging themselves and recovering. SwissAir took off for Europe six minutes later.

What went wrong? As always it will take time to know the details. But it appears that there was some mammoth failure of communication or awareness among the Kennedy controllers. Tower and ground controllers read out tens of thousands of these takeoff and taxi clearances all day, every day. All it takes is one serious lapse to bring on a disaster.

And why wasn’t this the lapse that turned into a disaster? Mainly because the SwissAir crew that had already pushed in its throttles for takeoff saw the danger ahead and immediately responded, while there was still a chance to slow the plane down.

Good for the SwissAir team. But jeesh.

2) National Airport, Washington DC, April 18, 2024.

National Airport does not have parallel runways, like those at Kennedy. Instead its three runways have a triangular layout, with each of them crossing both of the others. This makes the ballet of coordinating ground movement even more complex.

The drama of this close call, clearly shown in the clip below, is that one plane has been cleared to taxi, directly into the path of another plane already cleared to take off. In specific, a Southwest airliner (shown in blue below), leaving the terminal, is cleared to taxi across Runway 4, while a JetBlue airliner (in green) has been cleared to take off along that same runway. The results could have been very bad—as you will clearly hear in the urgent voices of people in the control tower when they just-in-time recognize the mistake.

Time-stamp guide for the video above:

0:30 A ground controller gives Southwest its taxi instructions, including the magic words “Cross [Runway] 4.”

0:42 The pilot reads the instructions back, stressing “cleared to cross 4.”3

1:10 A different controller clears JetBlue to take off on Runway 4, even as Southwest taxis toward it.

1:32 This begins the aural record of dawning panic in the DCA control tower. A voice in the background sees what is happening and says “Tell Southwest to stop.” Within a few seconds a controller is yelling on the radio “SOUTHWEST STOP.” Another controller yells “JETBLUE STOP.” In nearly 2000 hours of listening to air-traffic transmissions in a cockpit, I have never heard controllers needing to shout emergency commands this way.

1:43 The pilots of both airplanes report that they have stopped—JetBlue with its takeoff roll, Southwest with its taxi.

1:50 A different controller takes, well, control of the situation, telling the planes what to do and where to go. From the confidence and command in her voice I’d bet that this is a supervisor or instructor-controller, immediately stepping in for a trainee or novice.

2:57 The Southwest crew takes the unusual step of asking for a phone number to call. They know there has been an incident. Presumably they want to register that they were properly following a clearance when they taxied toward a serious problem.

The old line about Wayne Gretzky was that he skated not to where the puck was but to where it was going to be. Starting around time 1:32 we hear the Gretzkys of the control tower realizing what was about to happen and trying to head it off.

Good for them. And that is how I am used to hearing ATC operate. But again, jeesh.