Forgotten Americans (of a different type)

Some people, institutions, and ideas that could use more of the media spotlight.

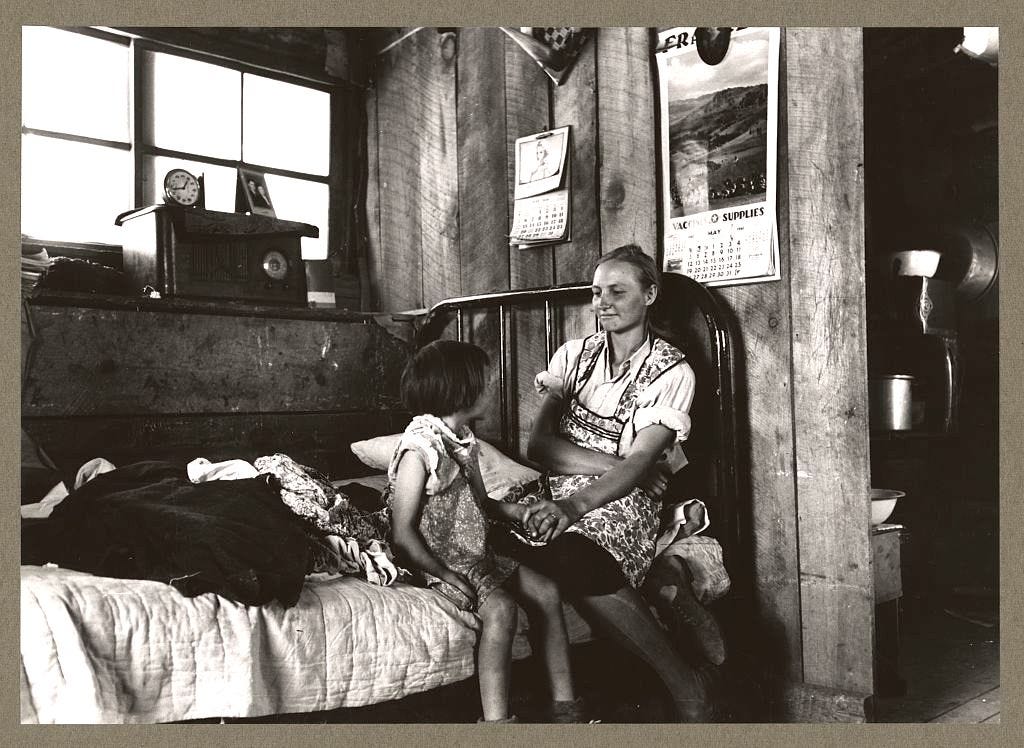

From Russell Lee’s famous series of photos of Depression-era Americans, created for the Farm Security Administration. This one is identified as showing Mrs. Caudill and her daughter, of Pie Town, New Mexico, listening to news on their radio in the summer of 1940. Who gets noticed, and overlooked, in American life has been one of the country’s enduring fault lines. (Library of Congress photo.)

This post is about several articles, recordings, and events I found interesting and wanted to share. Their loose connecting theme involves the parts of local, national, and global life that deserve more public and media attention. Yes, I know, everything deserves more attention. But overall I think these themes deserve an extra boost.

1) Who are those elusive ‘Biden voters’?

The most interesting essay I’ve read recently about American political dynamics came out early this month. It was by Nicholas Grossman, of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and it was on the Substack site of The Bulwark, an anti-Trump conservative publication.

The piece was called “The Media Still Doesn’t Get Biden Voters,” and you can read the whole thing here. I come back to it, and hope you’ll read it, because I think it’s genuinely important and original, and different from what you’ll see elsewhere.

Grossman’s point, to oversimplify, is that we hear endlessly about the minority of Americans who support or tolerate Donald Trump. We hear from them at Trump rallies, we listen to what they say in diners. By comparison, we hear little about the majority of Americans who oppose him. As Grossman says in the opening to his piece:

Conservative and mainstream media don’t agree on much, but one point of consensus is that everyone should work harder to understand Trump supporters. The implicit message: You don’t have to agree with the populist right, but you should be listening to, empathizing with, and engaging them more.

A common style of this coverage is the safari to “Trump Country,” in which journalists from various outlets, most of whom live in big metropolitan areas, go to a rural community or Rust Belt town and talk to Trump voters, often white, working-class men in diners.

He points out the obvious contrast with coverage of the current president:

Reporters don’t do safaris to “Biden Country,” seeking to understand the voters who put him in the White House. While there are pieces explaining how, for example, black women in Georgia suburbs made a big difference in the 2020 election, there’s nothing approaching the ongoing coverage of white men in Ohio diners.

You can think of a lot of forces leading to this imbalance: Trump is an exception to all previous rules, so he naturally draws coverage on man-bites-dog principles. Trump is a showman and strives for whatever will draw a crowd; news organization know they, too, can draw crowds by covering him. Joe Biden has less sizzle to start with, and he works toward being as steady, “normal,” and no-drama as possible. Trump has taken over an entire party and rallied extremist and violent support. The results, including violence, demand a different kind of coverage than Biden’s unglamorous though relentlessly effective plod toward legislative success. And so on.

But however understandable its origins, the imbalance in coverage is real—and destructive.

-It is destructive in making Trump-extremist forces look numerically stronger and more united, and the opposition look weaker and more fragmented, than either actually is.

-It is destructive in making horse-race-minded political journalists worse at the one thing they supposedly know how to do, which is understanding electoral trends. Every major electoral outcome since Trump’s win in 2016 has been at “surprising” odds with the consensus mainstream predictions (as detailed here). And every one of the “surprises” has been in an anti-Trump, pro-Democratic direction.1 It is as if weather forecasters acted “surprised” by the nonstop series of record-hot days.

-And it is destructive in leading a horse-race-minded press to underestimate the genuine authoritarian threat that Trump and his allies represent. Too much attention to how, say, Ramaswamy stacks up against DeSantis or Trump. Too little attention to what any of them proposes to do. This is the subject of a trenchant, widely praised new column by Will Bunch in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Grossman makes an excellent case that there is a there there, when it comes to support for Biden and for the Democrats of Biden’s era. The article does something important I haven’t seen elsewhere: It applies the familiar “let’s understand the Trump voters” approach, but to a Biden coalition.

Grossman marshals facts and figures to show the breadth of support for Biden and the Democrats among lower-income and less-educated voters. Ie, the ones their party supposedly ignores. Then he says:

In addition to Biden voters not feeling like elites—or, by objective measures, largely not being elites—here are some other things about them that conservative and mainstream media don’t seem to grasp (or at least doesn’t think are nearly as worthy of attention as Trump supporters):

Millions and millions of Americans are, for lack of a better term, Bidenists. Many don’t have strong feelings about Biden himself, and some are quite critical of him, but they tend to react to societal disruptions by seeking normalcy, not trying to increase the chaos.

Bidenists like a president who shows empathy, though they may not have realized that until confronted with the opposite. It’s not a coincidence that George W. Bush’s approval rating shot up after 9/11…

Bidenists actually mean what they say about democracy….

Bidenists include civil servants you’ve never heard of, who don’t get any attention (or much pay), but keep all levels of government running. These civil servants actually meant their oath of office.

There’s a lot more in the article about the traits that define “Bidenists,” a group that seems to be previously unnamed in political coverage. Biden voters have mostly been defined as a kind of “negative space,” a group significant for what its members are not. They were not Bernie Sanders supporters in the primaries. They are not Trump supporters now. In general the picture has been of people unenthusiastically “settling” on Biden as the least-bad choice.

In life but especially in politics, things become more “real” when you give them a name. “Reagan Democrats” in the 1980s, “soccer moms” after that. “Bidenists” may not have quite the same ring. But by supplying a name Grossman may have made the phenomenon slightly more real.

While I’m at it, a few more articles on the gulf between real-world American political realities and standard “guy in a diner” reports:

From my one-time colleague and longtime friend Kathy Gilsinan, a very good piece for Politico about surprising current manifestations of the connection between work and “masculinity.” It’s here.

From Stephanie McCrummen late last year in the Washington Post, a related and very good article about how “Red State” America differs from most journalistic stereotypes.

From our friends at Daily Yonder, a piece about a new documentary on life in a part of Appalachian Ohio mainly known for its opioid struggles. One of the film’s producers, Amanda Page, says that she was influenced by the documentary Moundsville, on a former manufacturing center in West Virginia. I’ve written frequently about that film and endorse it.

From Jesse Nathan, an op-ed in the New York Times on why real-world life, day by day, in “red” and “blue” states is less starkly polarized than usually portrayed by national media or in political speeches.

From David Fishman, last year on his Substack site, a revealing comparison of life in rural Maine with life in rural China.

2) And what is this ‘industrial policy’ you speak of?

I have a dog in the fight over the previous point, #1. My wife, Deb, and I have been reporting over the past decade that daily life across the nation—town by town, neighborhood by neighborhood, person by person—is less embattled and polarized than campaign speeches or national news usually suggest.

I also have a stake in this point, #2. Back in the late 1980s, when our family was living in Japan, I wrote many articles and two books about the limits of what we would now call “neoliberal” economic policy.2 The essence of the argument, then as now, was whether “the invisible hand” of economics was infallible as well, so that whatever market-forces dictated would be most efficient and beneficial all around.

Long before he became a Broadway icon, Alexander Hamilton was Mr. Industrial Policy for the fledgling United States. (National Institute of Standards and Technology image.)

As I argued in a cover-length story for The Atlantic a full 30 years ago, blind faith in laissez-faire was not only suspect on common-sense grounds but also factually at odds with the story of American economic growth, from Alexander Hamilton’s era onward. A study of economic history, as opposed to economy theory, would show that the U.S. government had frequently intervened to shape (and improve) the path of industrial development. In the 1800s, this ranged from railroads and canals to land-grand universities and agricultural research. In the 1900s, it ranged from aerospace to biotech, from computer chips to housing and roads. Space, sustainable energy, advanced manufacturing are only a few of the counterparts now.

Back in the 1990s, you could count on the predictable WSJ editorial page or “leaders” [editorials] in the Economist to attack the heresy of “industrial policy.” The WSJ is still doing so now. But it is amazing how fast the rest of the world has moved on—and, in the United States, has done so to a strikingly bi-partisan degree.

Cynically you could argue that party differences don’t matter when it comes to carving up government benefits. True enough. But less cynically I would say that it genuinely deserves notice when national-level Republicans and Democrats agree on the potential benefit of policy changes to promote U.S.-based supply-chains, enterprises, and jobs. You could almost call these “industrial policies”—as a number of writers have done.

A brief reading list on this trend:

From Michael Schaffer, in Politico, a piece on the GOP’s internal battle over these policies.

From my longtime friend Clyde Prestowitz—who was a senior US trade official when I was living in Japan—a piece on the inevitability of industrial policy.

From another longtime friend, Michael Lind, a piece last year with the prescient title “Who’s Afraid of Industrial Policy?”

From Jeff Ferry, a piece this month called “Industrial Policies Gains Support in Academia.”

From Noah Smith, the most recent of a series of Substack posts on the topic.

Something is happening. Watch this space.

3) And what is this ‘usable past’?

We all have a finite number of Main Ideas. One of mine is: The U.S. has always been in trouble. Its historical greatness consists of finding ways to get out of each era’s troubles and to prepare for what comes next.