Another Way to Help Ukrainians: Let Them In

The United States should prepare, now, to lead the way in welcoming refugees. Here is what that means in practice.

As I write, no one knows what the next hours or days will bring in Ukraine.

Will Vladimir Putin pay a price for his cruel and reckless over-reach? A personal and financial price, if sanctions can touch him and his holdings? An even steeper price, through a putsch? Will Volodymyr Zelensky be known ten years from now as the leader whose bravery and eloquence drew the world’s support and saved his country? Or, ten days from now, as a tragic symbol of his country’s doomed fate?

Will this past week’s unexpected solidarity among NATO members endure through weeks to come, as the pain of sanctions extends beyond their immediate targets in Russia? Might Putin be cruel and reckless enough to extend the military risk even further? And how will politics in democracies that cope with Russia, starting with the United States, change after a reckoning of those who stood with Putin even until this week?1

I am not making odds on any of that, because it’s impossible.

I do know about one aspect of the United States’s response, which deserves more attention, starting now. That involves preparing to welcome refugees:

As a declaration of policy, U.S. officials should say, as soon as possible, that this country will set an example in the scale and quickness of its willingness to accept people who have been forced from their homes.

And as a practical matter, U.S. officials should pay immediate attention to revving up the carefully designed, but recently neglected (or sabotaged), public and private arrangements through which generations of refugees have found new opportunities for themselves, and made America stronger through their presence.

No one in Ukraine chose to be displaced. But hundreds of thousands of them have already been uprooted, and—whatever happens—many more will be. The U.S. should prepare for many of them to arrive here, and should be glad of that.

Last fall, as the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan and the Taliban moved in, I did a long post on the modern history of U.S. experience with refugees. You can read the whole thing here.

Its main point was that the United States had looked worst in history’s eyes when it had turned its back on, and closed its doors to, people who were forced to leave their homes. (The most notorious case being the S.S. St. Louis in 1939.) And that it had been truest to its best version of itself when making more room for refugees. As it happens, it had also helped itself in economic, academic, cultural, linguistic, and other ways when doing so.

It had several subsidiary points. This post updates that earlier dispatch, with specific relevance to people from Ukraine.

Reality 1: The U.S. is near a modern low in refugee admissions.

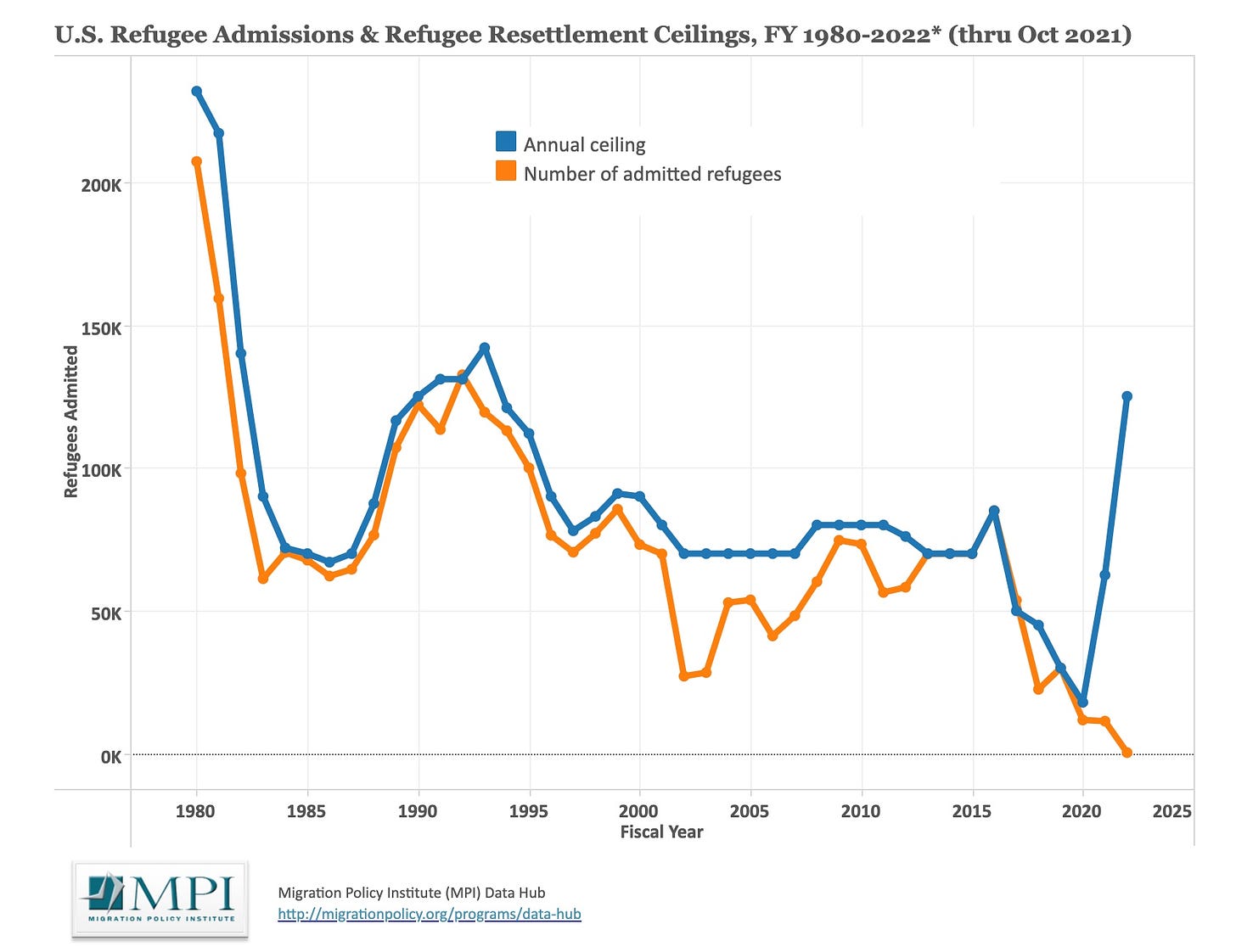

This chart from the Migration Policy Institute, updated from the one I used last year, shows that current arrival levels for refugees are near a modern low.

The blue line shows the legal ceiling that presidents set for annual arrivals; the orange line shows how many people actually came in.

As I pointed out earlier, you can roughly match the pre-2016 ups and downs to wars and turmoil that increased refugee flows. The peak on the left side of the chart reflects the long aftermath of the American war in Vietnam.

The plunge in arrivals in 2020 was largely due to the pandemic. But the dramatically lowered ceilings of the four preceding years were explicit Trump-era policy. The Biden administration raised the ceiling, in two stages, from its Trump/Stephen Miller-era lows to its current 125,000 per year. Because of the turmoil in Afghanistan starting six months ago, and Ukraine now, it will need to go up again. But as the chart above shows, the real crisis now is not the theoretical limit but the number of people getting through the process.

Reality 2: The machinery of immigration badly needs repair.

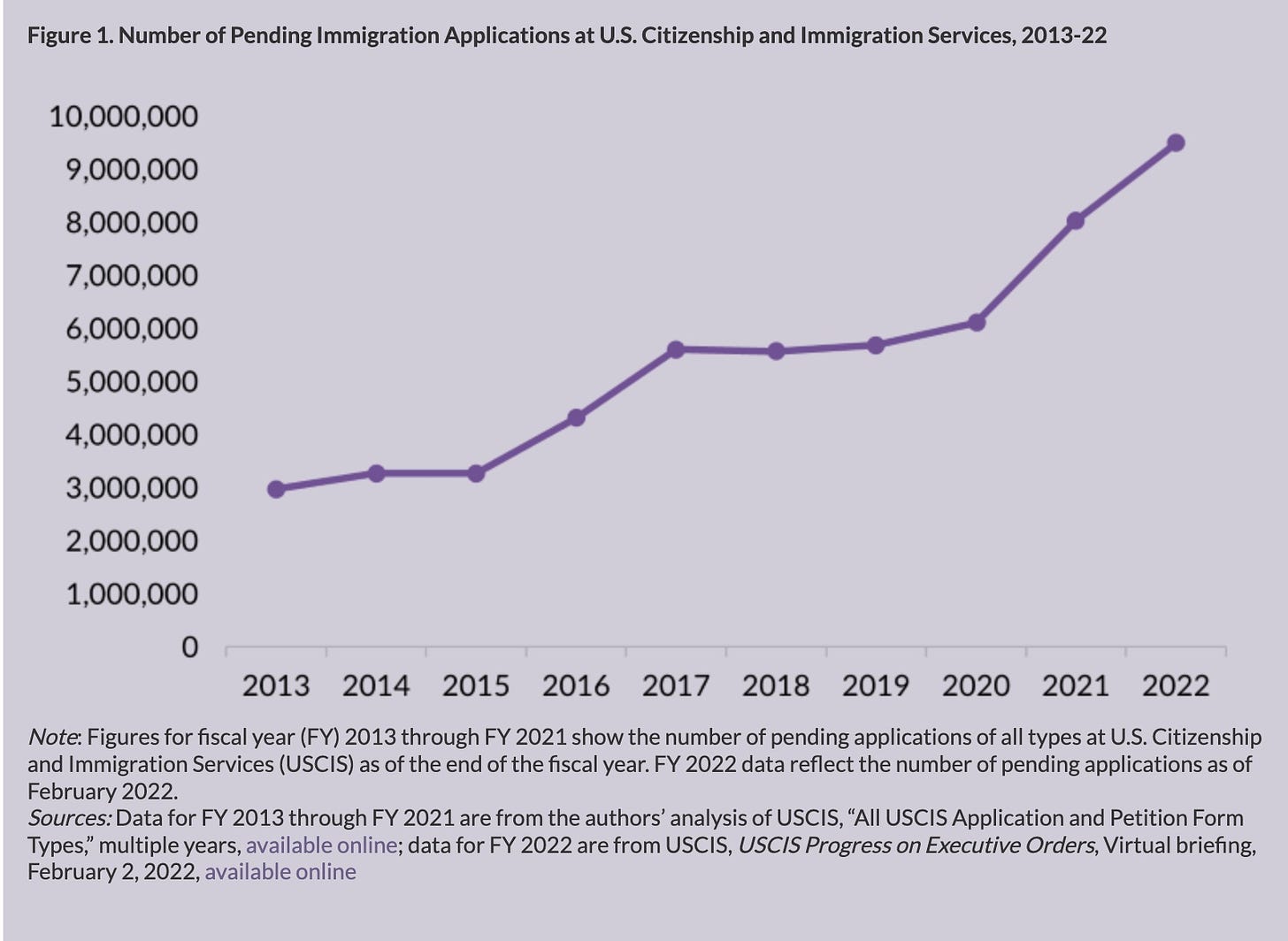

Another chart and new report from the Migration Policy Institute sum up the problem. Millions more people are waiting simply to have their applications for refugee, asylum, immigrant, or other status considered, regardless of whether they ultimately get in.

Problems long overdue for attention sometimes get addressed only when emergencies arise. (This is an age-old American problem, dating back to William James’s seminal essay in 1910, “The Moral Equivalent of War.”) The machinery of immigration should have been repaired long ago; the emergency in Ukraine is an immediate reason to do so.

Reality 3: Refugees end up all over the country.

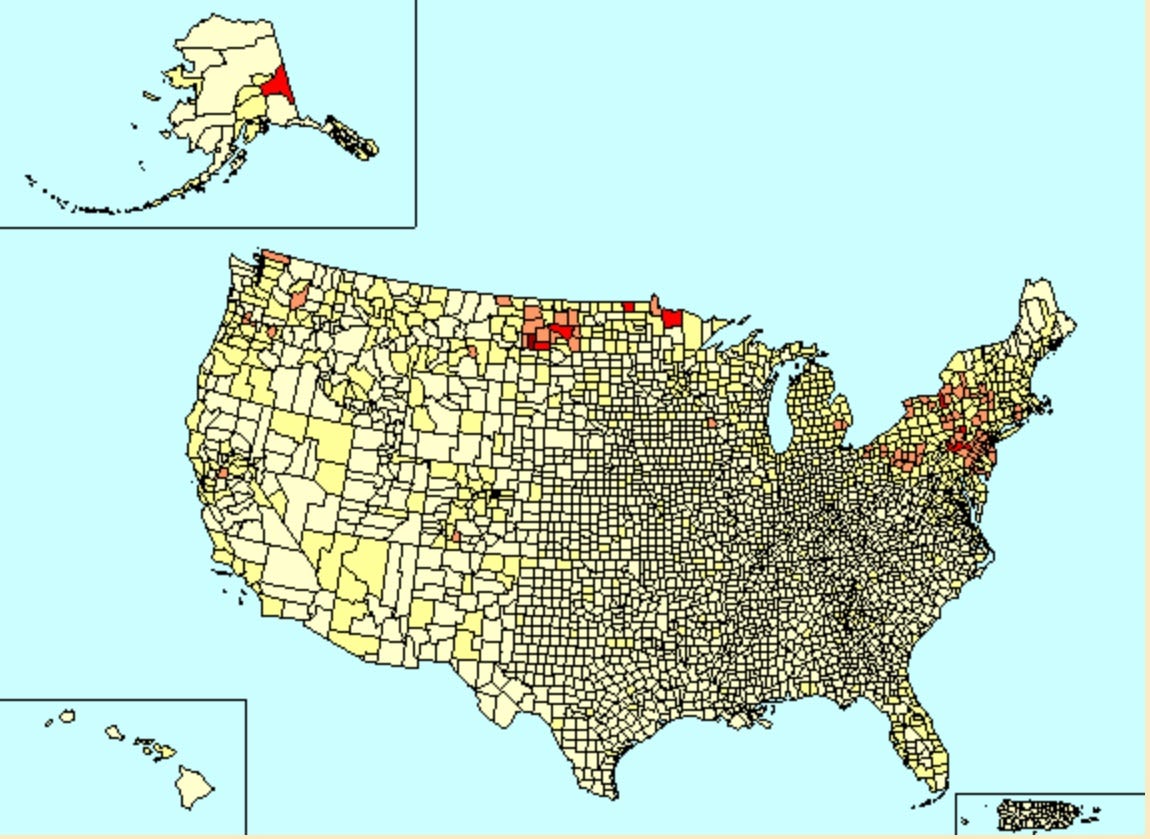

This map below is a screenshot of a map by Julia Holtzclaw, from the “Living Atlas” collection by our friends at Esri. The online interactive version, which is called “How many refugees are in your city?” and which you can click on here, allows you to zoom in and out and see data for any community. It covers arrivals from 2002 to 2018.

The big picture, as this map suggests, involves two contradictory realities. On the one hand, the greatest concentrations of refugees, like the greatest concentrations of people in general, are in the largest metropolises. The New York-New Jersey area. Los Angeles and its surroundings. Houston, Chicago, and so on. More details here.

On the other hand, the refugee-diaspora spreads across more of America than you might think. Some places are long-established strongholds of refugee-reception: for instance, the Twin Cities area in Minnesota. But smaller cities like Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Erie, Pennsylvania; Fresno, California; and Burlington, Vermont; have played an outsized role.

Given existing Ukrainian-American settlements in the Northeast and upper Great Plains, more of this era’s refugees will probably end up there than, say, in Texas or the South. (The map below is the pattern of Ukrainian-American population, according to the 2010 Census.) But most of the country has been part of the refugee-resettlement process.

Reality 4: Private and religious organizations have a long track record of the on-the-ground work of helping refugees.

Refugee levels are set by national policy. But the detailed work of finding homes, looking for jobs, teaching English (and other skills), and generally surviving, falls to organizations that have specialized in refugee resettlement. Various parts of the federal government, notably the State Department and Health and Human Services, have contracts with the organizations to pay for this work. Many though not all of the groups are faith-based: Lutheran Social Services, Catholic Charities, HIAS, and others.

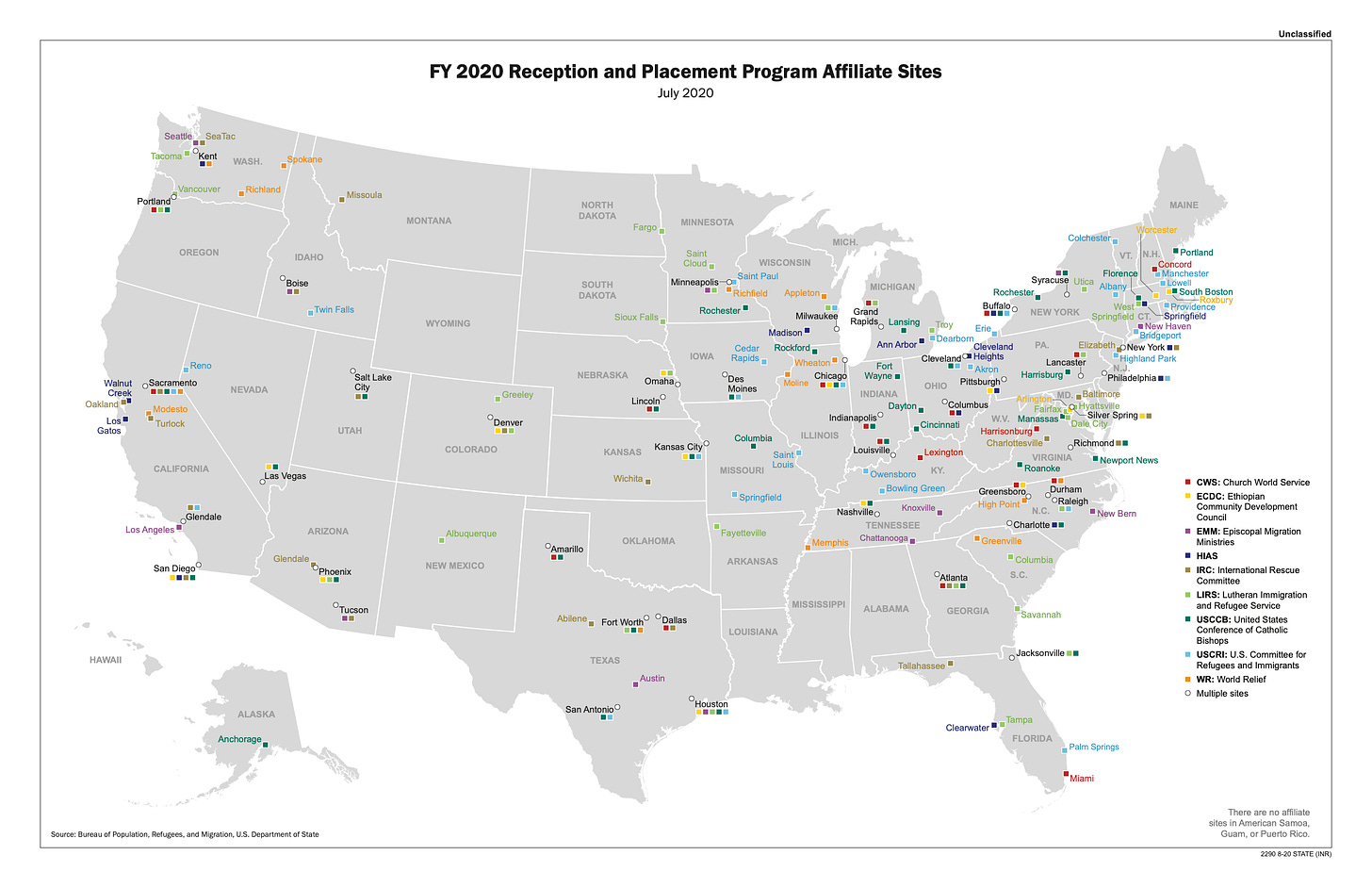

Here’s a map from the Refugee Processing Center of some local affiliates. It gives you an idea of the range of resettlement efforts.

These places and organizations will be on the front line in helping refugees from Afghanistan, Ukraine, and elsewhere. Fortunately they have a lot of experience. Deb Fallows has written extensively about what they do. For instance, this about the Multicultural Community Resource Center in Erie. And this, about the Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program. And this, about what she heard from organizations across the country just after the 2016 election.

Reality 5: Refugees, overall, ‘do well.’

Economic payoff is not the main reason to admit families who have been forced from their homes by bombs or tanks. But, historically, refugee flows have led to above-normal rates of entrepreneurship, and second-generation academic achievement. Decades ago, I did articles for Texas Monthly and The Atlantic about whether refugees from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia would “make it” in California and Texas. (I said: They would.) Now, look at university-honors lists in those states.

For more systematic studies, consider this one, on economic progress among refugees from Vietnam. And this, about Haitians. And this, about Cubans.

What will happen with people from Ukraine — and Afghanistan? Again, their economic and academic promise is not the reason to welcome them. But historical evidence suggests it will be a plus.

For now I am not getting into some of the tangles of refugee policy. For instance, why it might be politically “easier” to welcome a wave of refugees from a country whose people are mainly Christian, and mainly white. (Five years ago, the country that sent most refugees to the U.S. was the Democratic Republic of Congo, followed by Burma/Myanmar and Syria.) As the photo at the top of this post shows, families fleeing warfare in Ukraine can be surprisingly diverse.

I also don’t know the exact number of refugees the U.S. should commit to accept. (No one knows how many people from Ukraine might ultimately need help.) I know only that the U.S. should take the lead, and set an example — as it appears to have done so far in urging the rest of Europe to apply sanctions.

Making a new home, for people forced out of their own homeland, is the right thing for America, and for the world.

Three important reminders: First, the only change that the Trump campaign made in the Republican platform in 2016 was to remove any pledge for military assistance to Ukraine. I wrote about this at the time. Second, when Donald Trump was impeached the first time, the main reason was his threat to withhold military assistance to President Zelensky of Ukraine, unless Zelensky would help him find dirt on Hunter Biden in the 2016 campaign. Third, all Republican Senators stood behind Trump on this issue, except for Mitt Romney.

A good friend of mine created the Columbus Crossing Borders art project/film several years ago (https://www.columbuscrossingbordersproject.com/about.html). It's one of the most profoundly moving experiences I've had to bring home the reality about what it's like to be a refugee.

Artists worked collaboratively with their neighboring partner to "cross over" some elements of each painting into their partner's. Some of the artists were refugees, themselves. This happened during the height of the Syrian refugee crisis, and during the Trump administration, when there was a lot of ugly rhetoric about, and policies toward, refugees. But the art created and the refugees featured in the film helped open up a conversation that would not have happened otherwise.

Thank you for this deep and thoughtful article!

No one wants to flee their country: poverty and war are the biggest drivers of refugee flows. But, most immigration research centers point to the positive influence of immigration on America, and to the empty, depopulated states in many parts of the country - everyone fled to the city in these states. They welcome New Americans. Immigrants pay taxes, generate new businesses, and succeed in every way.

Let's look instead at the arms market profiteers that profit off war, jumping for joy that they can sell more missiles. And at the military industrial complex around the world just itching to spread nuclear weapons through proliferation.

About refugees, with all due respect, this statement below in the comment section is not at all correct. Citation for this? "...And the Census Bureau projects that over the next four decades, the population will increase by nearly 80 million--equivalent to four New York States--90% of that from immigration. "

President Eisenhower : Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

As Barney Frank said, Unless you are speaking Navajo, you are from somewhere else.

https://bangordailynews.com/2022/02/22/opinion/opinion-contributor/america-cannot-forget-those-left-behind-in-afghanistan/