The most encouraging front-page headline I’ve seen in the New York Times in a long time was this, from Labor Day. It was on a story by Miriam Jordan and Jennifer Steinhauer, and it said:

For the moment, let’s set aside the obvious complications and caveats: Who exactly made it out of Afghanistan, and didn’t. When and where the inevitable glitches and oversights in the resettlement process will first show up. Whether and where either a “genuine” local backlash against new arrivals might appear, or a politicized, “Stephen Miller-style” movement might be ginned up.

We can deal with all of that in due course. For now my purpose is to lay out some trends and realities of the refugee-resettlement process, as I have observed and reported on it for more than 40 years. I think of these as benchmarks by which to judge how the latest phase is going.

What are my views based on?

-In the early 1980s, I spent months on a number of Atlantic reporting projects, mainly in Florida, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, and California, covering the refugees of that era. Those in Florida were mostly from Cuba or Haiti. In the other states they were mostly from Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and other parts of Southeast Asia, and Mexico or parts of Central America. While living in Malaysia in the late 1980s my wife, Deb, and I spent time in refugee camps across Southeast Asia.

-Before that, when I was growing up during the Boomer era, some of my schoolteachers and my parents’ friends had been refugees from Europe, pre- and post-World War II, or from Japan. Some children I knew were from families that had left Korea after its war, or fled mainland China or Taiwan in that era.

-After that, starting in 2013, Deb Fallows and I reported extensively on modern-era refugees—people from Sudan, Somalia, Congo, Burma, Eritrea, and other African, Asian, and Latin American sites. You can see some of those stories collected here.

Now, the big realities that I think should be baselines for thinking about today’s incoming refugees.

1 Numbers

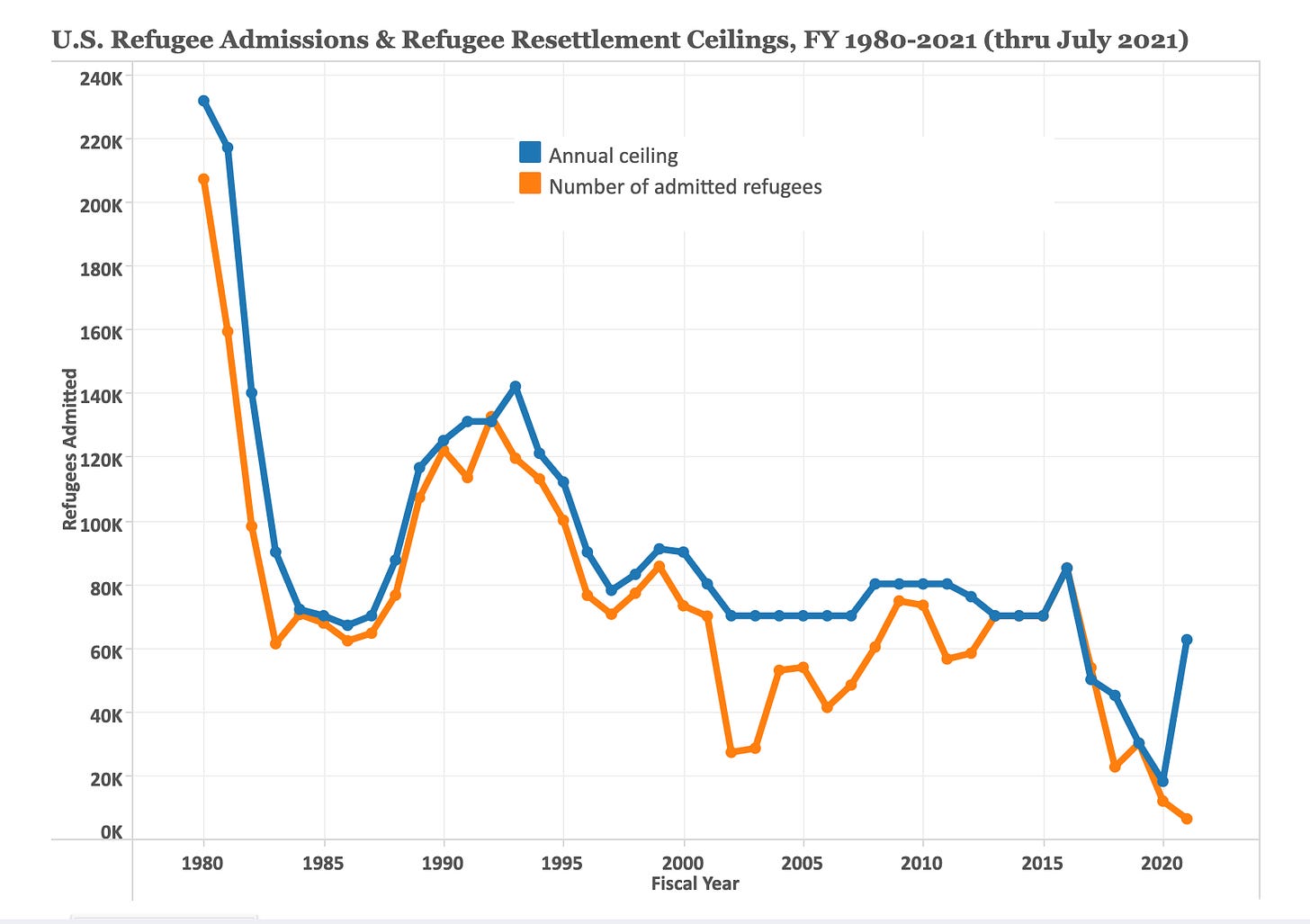

By modern standards, recent refugee-arrival levels in the United States have been low. This chart, from the Migration Policy Institute, gives you some perspective:

The blue line shows the legal ceiling that presidents set for annual arrivals; the orange line shows how many people actually came in.

You can roughly match the pre-2016 ups and downs to wars and turmoil that increased refugee flows. The peak on the left side of the chart reflects the long aftermath of the American war in Vietnam.

The plunge in arrivals recently—fewer than 12,000 refugees admitted in 2020—is largely due to the pandemic. But the dramatically lowered ceilings of the four preceding years were explicit policy. The annual ceiling when Donald Trump took office was 85,000. When he left, it was 18,000, and just before last year’s election he announced a plan to lower it further to 15,000.

For now the point is: over the past five years the U.S. has not been taking in many refugees. By its own modern standards, it has “room” for more.

2 Location

This map is a screenshot of a map by Julia Holtzclaw, from the “Living Atlas” collection by our friends at Esri. The online interactive version, which is called “How many refugees are in your city?” and which you can click on here, allows you to zoom in and out and see data for any community. It covers arrivals from 2002 to 2018.

The big picture, as this map suggests, involves two contradictory realities. On the one hand, the greatest concentrations of refugees, like the greatest concentrations of people in general, are in the largest metropolises. The New York-New Jersey area. Los Angeles and its surroundings. Houston, Chicago, and so on. More details here.

On the other hand, the refugee-diaspora spreads across more of America than you might think. Some places are long-established strongholds of refugee-reception: for instance, the Twin Cities area in Minnesota. But smaller cities like Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Erie, Pennsylvania; Burlington, Vermont; and Dodge City, Kansas have played an outsized role.

The circumstances vary region-by-region. But Erie’s story is interesting as an illustration of a city whose population had long been declining, and that has embraced refugees as a source of entrepreneurial, economic, and demographic vitality.

You can read more about Erie’s work on this front here, here, here, and in the video below, made during the pandemic by our friends Nick and Jessica Taylor of MenajErie studios. I am confident that you will be surprised if you start watching this brief video.

3 Who does the work

The overall number of refugees admitted is a national policy—and is affected by global trends.

The initial attention to refugee-resettlement naturally concentrates on ad hoc, volunteer, and person-to-person efforts.

But in the long run, the detailed work of finding homes, looking for jobs, teaching English (and other skills), and generally surviving, falls to organizations that have specialized in refugee resettlement. Various parts of the federal government, notably the State Department and Health and Human Services, have contracts with the organizations to pay for this work. Many though not all of the groups are faith-based: Lutheran Social Services, Catholic Charities, HIAS, and others.

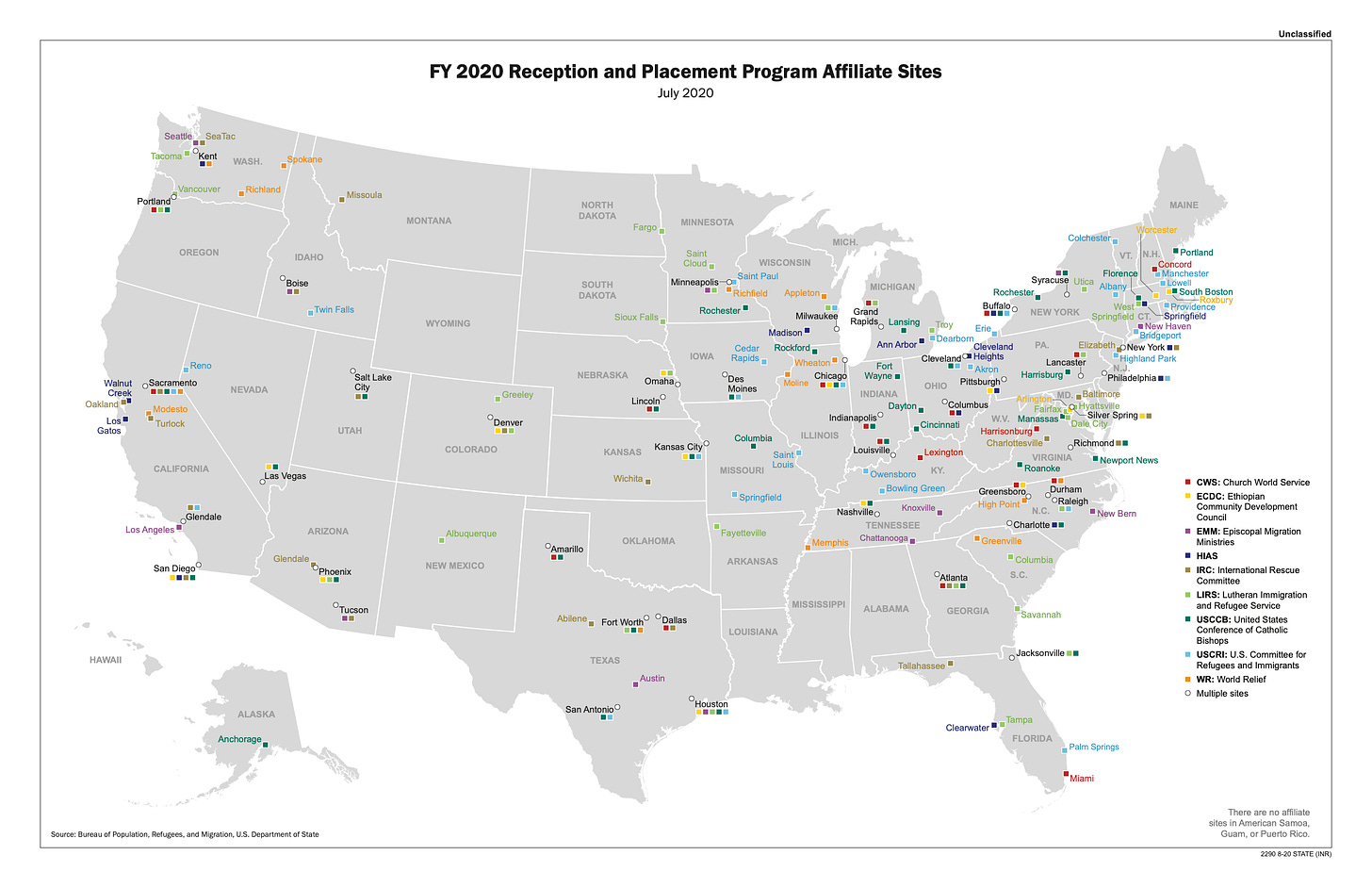

Here’s a map from the Refugee Processing Center of some local affiliates. It gives you an idea of the range of resettlement efforts.

Deb Fallows has written extensively about these organizations and what they do. For instance, this about the Multicultural Community Resource Center in Erie. And this, about the Vermont Refugee Resettlement Program. And this, about what she heard from organizations across the country just after the 2016 election.

One of the most powerful scenes in our HBO film Our Towns is in the Lutheran Social Services office in Sioux Falls. There Mohamed Ahmed, who had arrived as a refugee from Somalia and is now a medical consultant for newer refugees, tells his story.

As he says in the film, with a self-aware “can you believe it!” smile:

I’m a refugee.

I’m a Black.

I’m originally from Somalia.

And—I’m also a Muslim!

Which means, I’m a combination of four elements.

…. I am not a threat.

You’ll have to see it for yourself to see the full impact. But you get the idea.

4 How refugees do

If you want econometric studies of refugees’ economic and educational achievements, in the first generation and beyond, I invite you to start with the reports from the Migration Policy Institute. For instance, this one, on economic progress among refugees from Vietnam. And this, about Haitians. And this, about Cubans. There are plenty more.

But I really invite you to think “qualitatively rather than quantitatively,” as the social scientists say. And think about what including, or rejecting, refugees has meant in America’s history.

Reflect on stories like this one, about “True Tender” and “Brings Luck,” who went from Burma to Vermont.

Reflect on the immigration-policy decision the United States should most grievously regret. That is denying entry to the Jewish passengers aboard the M.S. St. Louis in 1939, and consigning them to their fate.

Reflect on what Mohamed Ahmed — originally of Somalia, now of South Dakota — said at the end of our film interview:

Ninety-nine per cent of the people living in America now are either refugees or immigrants.

The reason why America is a great country now is because of people like me—and you, and everyone.