‘You Know Nothing of My Work…’

Where is Marshall McLuhan when I need him? Or: What Jimmy Carter could have taught Jacques Barzun.

A famous scene from Woody Allen’s 1977 movie, Annie Hall. Allen (center), playing Alvy Singer, is in a fight with a know-it-all man in a theater line played by Russell Horton (left). They disagree about who better understands the works of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. To clinch his argument, Alvy Singer says, “I happen to have Mr. McLuhan right here,” and pulls the real McLuhan out from behind a movie poster. McLuhan wraps up the scene with “you know nothing of my work!”

I have just had my Alvy Singer moment.

This will be a little different from the standard post. It concerns the only time I can remember when I was reading a book and actually yelled out loud, What the hell?

For an upcoming project, I’ve been reading a series of books by and about William James. These days it is necessary to add “the philosopher and psychologist William James,” or “the influential turn-of-the-20th century thinker William James,” or even “William James, elder brother of famed novelist Henry James.”

But in his time—roughly the half-century following the Civil War—William James was a polymath of huge consequence. He is best known for his books Varieties of Religious Experience and Principles of Psychology. He had also trained as a painter and as a medical doctor. Over the years I have frequently cited one of his essays, The Moral Equivalent of War, as a seminal work in American thought and culture. Here’s an example of when I did so, back in 2010.

Last night I was reading an engrossing and informative book by Jacques Barzun, called A Stroll With William James. These days it is necessary to point out that Barzun was a noted and prolific historian and author, who published well-received books well into his late 80s and died at age 104, in 2012.

A Stroll With William James was published in 1983. In its prologue Barzun contrasts William James’s great fame during his lifetime with his descent into “the twilight which for the great may follow death for fifty or a hundred years.” He gives this example:

That position in the shadows is well shown in the use made by President Carter, in an early message about the national need to conserve energy, of James’s essay title ‘A Moral Equivalent of War.’ [sic] The phrase could not be said to be familiar to the public and its meaning in James was obviously not clear to the speech writer.

Ahem.

As it happens, I was “the speech writer.”

And if Barzun were still around—I never met him—I would tell him that nothing could have been clearer in my own mind than the argument William James made in that essay. If Jimmy Carter were now able to answer questions about that speech, I believe he would say the same. Carter was in the flow of popular culture and must have seen the movie Annie Hall, which came out the same year he became president. Maybe he would think to say to Barzun, McLuhan-style, “You know nothing of my work!”

Now, the back story.

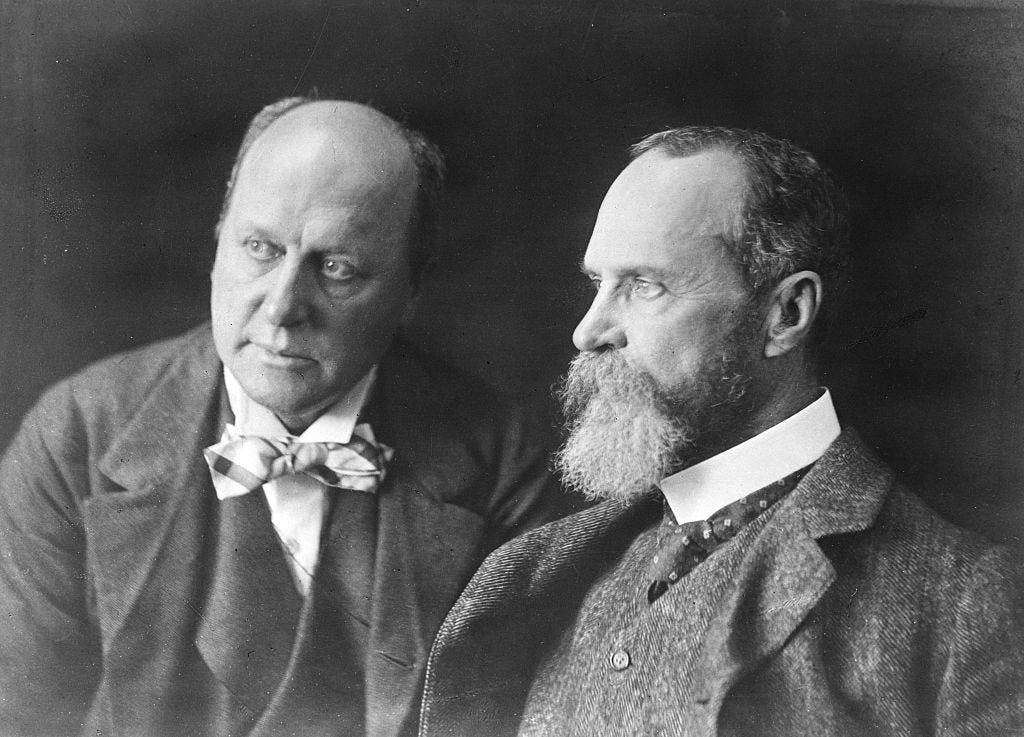

On the left, little brother Henry James. On the right, big brother William James. At least one of them has been quoted in a televised presidential address. (Getty Images.)

‘History is a bath of blood…’

Carter’s mentor during his years as a submariner was Admiral Hyman Rickover, founder of the Nuclear Navy. Carter’s campaign autobiography, Why Not the Best?, took its title from a question Rickover asked his subordinates when challenging them to do more. After Carter became president he turned to Rickover for counsel, especially in the early drafting and presentation of his energy-conservation plan.

Rickover knew the William James essay and wanted to refer to “Moral Equivalent” in the big national-TV launch speech for the energy plan. (How do I know this? Because I heard Rickover talk about it.) As he did with many of Rickover’s suggestions, Carter agreed. My job was to take instructions from the policy-makers, Carter on down, and convert them into a speech.

As it happened, a few years earlier in college I had sat through American history courses on William James and even written a paper on his “Moral Equivalent” concept. I thought that incorporating it into the speech would be a great idea—if Carter explained what it meant.

What it meant to me, in the oversimplified terms necessary in speech-making, was channeling the heroic aspects of warfare—the bravery, the passion, the fellow-feeling—toward positive rather than ruinous ends. As William James himself put it in the essay:

Modern man inherits all the innate pugnacity and all the love of glory of his ancestors. Showing war's irrationality and horror is of no effect on him. The horrors make the fascination. War is the strong life; it is life in extremis; war taxes are the only ones men never hesitate to pay, as the budgets of all nations show us.

History is a bath of blood.

His essay went on to explore how this love of glory, even this pugnacity, might be satisfied in other ways. How, in James’s terms, a “war against war” might be waged. The clearest practical example after James’s time would have been the Civilian Conservation Corps, under FDR. Or the Peace Corps under JFK. Or non-violent movements for civic or political reform. The Civil Rights movement in 1960s America. The successful Solidarity and “Velvet Revolution” efforts against Soviet control in the 1980s. The doomed Tiananmen Square resistance movement in 1989. A winning political campaign. Sometimes even a losing one. “We happy few, we band of brothers” was about a battle. Veterans of the Selma march must have thought of themselves in that same way.1

Models of passionate, non-violent “war” are explicitly what Carter had in mind in choosing this phrase. The US then seemed in permanent thrall to oil imports from the Middle East. Carter hoped that government, citizens, and even businesses could join in a non-violent liberation movement.

How do I know that is what he meant? You’ve heard the phrase, “in the room where it happened.”

Obviously things didn’t turn out the way Carter hoped or intended—on the grand scale, and even in that speech. As for the speech, my nonstop plea was: If you’re going to talk about “moral equivalent of war,” spend another line or two explaining what that means. Otherwise people might just be puzzled, or think it refers to some kind of holy war.

But I was the lowest-ranking among the many cooks in the kitchen for this speech. Maybe Admiral Rickover thought that everyone would get the allusion, and it would be insulting to spell it out. Maybe Carter thought that a reference to William James would be too fancy-pants. Whatever. The phrase went into the speech, bald.

More than 150 pages into Jacques Barzun’s otherwise excellent book he returns to Carter and his speech. He says that the phrase “moral equivalent of war”

is now famous in the Jamesian way, that is, widely used without understanding. It is the curse of the half-educated to seize upon something interesting and —a phrase, a title, an observation—and without further look or caution to fabricate out of their resources what they would make it mean.

Barzun goes on and on,2 and winds up saying that “The only public man I have heard using the phrase correctly is Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan.” It is too bad that he never thought to ask Jimmy Carter what he meant to say.

Curse of the half-educated indeed.

In a related essay James had written:

“Most of us feel as if we have lived habitually with a sort of cloud weighing on us, below our highest notch in discernment, sureness in reasoning, or firmness in deciding. Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake.”

Throughout human history, warfare, with all its horrors, had made people fully awake. That is the story of the literature of warfare from the Odyssey and Iliad onward. It was the story of the US Civil War, in living memory for William James and readers of his work.

“The White House under President Carter made a slogan of the Moral Equivalent at the beginning of the oil embargo that threatened our energy supply. Investigative reporters repeated the phrase without a second thought, and now it serves as a synonym for economizing fuel and power. What the voice from the White House hoped to say was that such self-restraint recalled the privations of wartime, which ought to be accepted with civilian fortitude. The meaning was the exact opposite of James’s proposal, whose intention was the release of aggression through useful expenditure of energy.”

Barzun's involvement makes me tell a story of my own about people who didnt know what they were talking about telling me that I didn't know what I was talking about. For decades I worked for and with physicists--great people, but occasionally condescending, some of them. Gradually I realized that I didn't have to put up with it. I developed some strategies, but I also posted this from Barzun on my office door: "It is an error to suppose that when a physicist talks about science he is bound to be more reliable than a so-called layman who has taken the trouble to inform himself and to think."

Glad to know you're a fellow member of the Club of Writers Who Weren't Listened To When They Should Have Been. It's almost an occupational hazard, in my experience, both as a political speech writer and a screenwriter. The best stuff. In the wastebasket. Thrown there by people who Would Not Listen To Reason (/snark).