What We Learned from the Wind.

On Wednesday, a cautionary prediction. On Saturday, the very thing that was warned against.

After the storm: Deborah Fallows in our neighborhood in Washington DC. Just beyond this fallen tree was another of similar scale, which smashed onto a car that was driving by.

This past Saturday afternoon, four days ago as I write, a brief but ferocious wind storm ripped through the Washington DC area.

The after-effects looked like those of a tornado, or a derecho like the ones that similarly tore through Washington in 2012 or did such damage in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, three years ago. On one street, enormous trees had been torn from the ground and thrown against houses, cars, and power lines. A few streets over, barely a twig looked disturbed. A weather station a few blocks from our house reported peak winds of 84 mph. In parts of town a mile away, winds were “only” in the 40s or 50s.

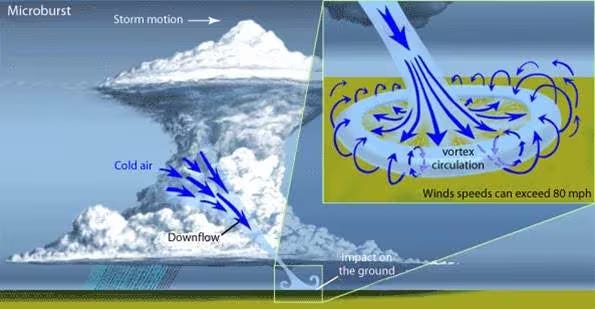

As an excellent explanatory article by Jason Samenow, Jeff Halverson and Dan Stillman in the Washington Post pointed out the following day, this phenomenon was neither tornado nor derecho but instead a “downburst.” All these forms of destructive wind arise from thunderstorms. But a downburst is essentially a torrent of colder air, which plunges from thousands of feet up and creates high-velocity vortices when it smacks into the ground. The Post included this useful illustration from the National Weather Service:

In aviation these powerful downdrafts are known as “microbursts.” Back in the summer of 1985, a microburst drove Delta flight 191, a huge Lockheed L-1011 Tri-Star, intro the ground as it was on approach for landing at Dallas-Ft. Worth. More than 130 people were killed.1 Ever since, airports, airlines, the FAA, and others have worked on warning systems to keep airliners a safe distance away from a downburst’s or microburst’s path.

Of course trees and houses cannot move themselves out of harm’s way. In its minutes of passage through the DC area, the weekend’s storm knocked down countless hundreds of towering, leafed-out trees and propelled them into houses, across wires, onto roads.

Its effects were the reverse of the usual environmental-injustice pattern.2 The main damage from the windstorm was not to buildings but to trees, and to whatever the falling trees struck. The greatest concentrations of the biggest, heaviest, oldest, leafiest trees in the region are in the richest, whitest parts of the District and its suburbs. The power-outage map from the utility company Pepco, which covers DC and parts of Maryland, showed well over 100,000 homes without power right after the storm—especially in Northwest DC and the Maryland suburbs. The WaPo reported the regional total at over 200,000. As I write, the Pepco outage map shows 500 houses still cut off, mainly in Northwest DC. At our house, the power came back on two days after the storm.

I mention this episode for three reasons: to express respect and admiration for those who coped with it; to underscore a warning about the pattern of which it is part; and to chronicle the “old” and “new” aspects of our own household’s resilience strategy.

First responders: respect and gratitude.

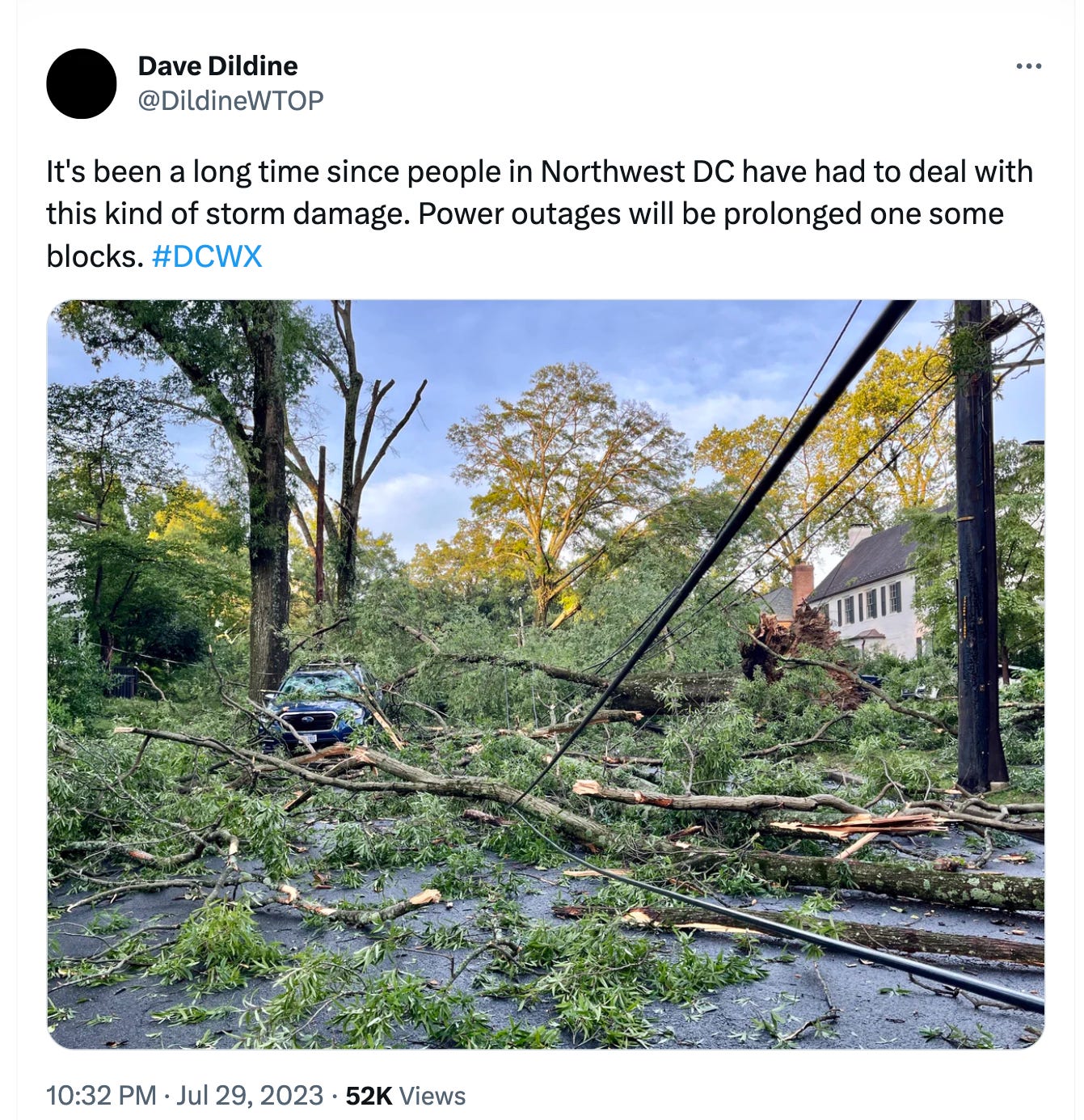

When the storm’s rain stopped and we walked among the tree-littered streets, we found it hard to imagine how long it might take before electric power, phone lines, internet service, and other connections could be restored. A tweet from a local TV newsman that day expressed the same stunned view:

Later that night, from the dark at our house, we saw police vehicles (which closed our street, because of a downed electric wire in the middle of it), ambulances, and some utility trucks rumbling through. The following morning, chain saws from tree-service contractors were everywhere. Later that afternoon, utility trucks from across the mid-Atlantic region rolled into town. Between 10pm and 4am on the second night, which was a Sunday and when it again started raining hard, we saw crews inspecting and connecting wires, once the tree branches and trunks had been removed.

By the next morning—yesterday—our power and internet came back on, as did, according to Pepco, the utilities for some 90% of those who had been disconnected. The houses still without power are mostly in nearby parts of the District and Maryland where the tree damage was so extensive that power-restoration may still take a while and overall recovery could take years.

We thanked the crews dealing with trees and power lines, and the police officers coordinating their efforts, wherever we saw them. They worked through the dark and rain for several nights straight, and managed a recovery faster than I would have believed, or hoped.

Double whammy: a prophecy.

Three days before the “downburst” hit, at the US Capitol a few miles across town, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing called “Beyond the Breaking Point: The Fiscal Consequences of Climate Change on Infrastructure.”

The theme of the hearing, overseen by committee chair Sheldon Whitehouse, of Rhode Island, was the impending double whammy of climate change’s impact on public infrastructure, including power and water systems.

Why a double whammy? Because more extreme weather puts more extreme demands on all parts of our infrastructure—and at the same time it makes that same infrastructure harder and more expensive to maintain.

There’s more demand on all fronts. More demand for power to keep people cool during intense heat, and warm during intense cold. More demand for water during extreme drought, and for flood-control during extreme rain. More need for repair crews like those we saw, for fire-fighters, for rescuers of all sorts.

Yet the same extreme weather attacks this same infrastructure. That is what we saw in concentrated form in DC. High-90s temperatures, with high humidity the preceding few days, meant air conditioners running all across town. But the same hot, wet air that made people swelter increases the chance of extreme storms like this one, which tore the local electric infrastructure apart.

The Senate committee went into all aspects of this challenge. You can watch the whole thing here. I particularly note the testimony of a well-known energy-and-environment expert named Susan F. Tierney, who as it happens is my sister. She began her testimony this way:

I have two main points to share with you today:

—First, the nation’s energy infrastructure is already being adversely impacted by the changing climate and related extreme weather events. Extreme cold and hot weather, droughts, flooding, wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, derechos, and other events are leading to power outages and fuel shortages.

—Second, given the nation’s dependence on well-functioning energy systems and the energy markets enabled by that infrastructure, the power outages and fuel shortages we are experiencing are producing great human suffering and costs. This happens both directly – by disrupting access to heating and cooling of buildings and by sometimes leading to loss of life – and indirectly – by disrupting electricity supply to other critical services (like water supply, wastewater treatment, transportation, phone, internet and other telecommunications) and causing energy prices to spike and to increase the costs and energy burdens on millions of households.

I hope you will read and think about the testimony and and warnings she offered, along with that of the other experts Sen. Whitehouse assembled.

Adaptability at the household level.

We were aware that we and our neighbors are more cushioned from extreme-weather disruption than practically anyone else. The phone lines, power, and internet might be down for a few days, but we could trust that they would ultimately come back. So far I have seen reports of only one death in the region because of the storm’s effects, in contrast to large-scale casualties from extreme weather elsewhere. Through most of the region mobile phones still worked. After the first night most of the major streets in DC were passable, thanks to the round-the-clock efforts of the crews. For us, in this cosseted neighborhood, it was a mild reminder of the effects of extreme weather.

And we adapted to it locally with a combination of very old and pretty new approaches.

Old ways

Candles. They do the job but need watching.

Flashlights. One of ours still did the job—the rest were so corroded from disuse that they no longer functioned. Lesson learned for next time.

Coolers, with ice. When the power went out, Deb unloaded ice packs from the freezer into cooler chests, where we could put perishables, and beer. That minimized having to open the doors to the freezer or the fridge and let warm air in.

The outdoor Weber grill. It cooked with propane and still worked.

The windows. We usually rely on ceiling fans for cooling. Atypically for Washington in the summer, the post-storm nighttime air was relatively cool and dry. Open windows let that air in.

Go to a hotel that had electric power? Maybe, if this had lasted for several days more. Back during DC’s “Snowmageddon” blizzard in 2010, when power (and heat) were off during sub-freezing temperatures for more than five days, I finally moved to a hotel to finish a big article on deadline. Deb stayed in our house, snowbound, to watch for repair people. Somehow our marriage survived.

New ways:

—Smartphone hotspot. This is so old it’s hardly new. But our only internet connection was our Android-phone hotspot. This was slow and shaky, because of local hills and trees and resistance to new cell towers. But better than nothing.

—Zoom lights. Those LED lights we got during the pandemic? Suddenly we viewed them not with dread but with gratitude. Here are two them taking a bow this afternoon, after the power came back on, and with their own lights turned off.

—A car serving as a battery. As mentioned before, we now own two vehicles: a 23-year-old stick-shift Audi, and a new Tesla Model Y. Of course the Audi has no power chargers, if you don’t count its from-another-era cigarette lighter. One of our sons reminded us that the new car has four USB-C charging ports inside. That is how we topped our mobile phones back up, when duty as internet hot-spots had worn them down.

Ways that are old, new, and eternal:

—The public library. Deb has written about libraries’ role as “second responders,” institutions that buoy up a community after first responders have made their rescues.

We walked to the the local Palisades branch of the DC Public Library system, which was miraculously (but routinely) open on a Sunday afternoon. Electric outlets. Desks. An open wifi system. “Just so you’ll know, after the library closes you can get the signal if you just sit outside the library,” one of the librarians told me.

“We’ve been packed,” he said. Gratitude to him and many others.

My thanks to George Lantos, a colleague from the Cirrus pilots’ community and elsewhere, for pointing out the connection between this downburst storm and the L-1011 tragedy.

A recent well-received book on these patterns is Susan Crawford’s Charleston: Race, Water, and the Upcoming Storm. You can read the admiring NYTBR review here. As it happens, she is our across-the-street neighbor and looked at the fallen trees with us.

Jim We were sailing in Long Island Sound in July 1949 when we heard that the Yankee game was interrupted by a tornado. We immediately went into our emergency drill: lowering sails and setting a tiny steadying jib.

When a tremendous storm struck Long Island Sound, we were safe. A yawl near us sailed under with four passengers drowned. We picked up a number of sailors whose boats had capsized.

In addition to our often practiced emergency drill, we kept a huge set of shears handy to cut away rigging in the event of a broken mast.

As you underscore, be prepared for the unexpected, which occurs with considerable frequency.

Except for those of us who have experienced the thrill of an in flight electrical system differential fault resulting in a (temporary, fortunately) loss of all electrical power at night, (the dreaded 6 light trip, to excite the old B727 pilots among us), the required flashlight in the kit bags of some airline pilots had become more of a dead battery receptacle. Technology tended to make us complacent if we let it. But we, most of us, learned to kept 'em in ready fashion, fortunately. I remember the Delta accident at DFW. Ten years earlier, in June of '75, Eastern flight 66, a B727 crashed short of the runway at JFK killing almost everybody. I remember seeing news reports that day with "officials" blaming the wreck on "pilot error". But NTSB later determined that a microburst caused windshear had been the cause, but added the caveat that the flight crew "had failed to recognize the severe weather hazard", and called that failure a contributing factor. Interestingly, the terms windshear, and downburst, were at the time all but unknown to most of us. The industry, with help and some heavy lifting by the FAA, the National Weather Service, the Airline Pilots Association and other interested parties quickly recovered the data from the EAL Flight Data and Cockpit Voice Recorders and built simulator scenarios duplicating all the data available, and got it programmed into flight simulators all over the world. For years, every semiannual trip to recurrent sim training included required instruction and evaluation on procedures to recognize and respond to wind shear phenomena, and specific non-intuitive changes were made to shear-emergency crew coordination and go-around procedures per aircraft type. For years afterwards it was ( and I hope still is) a staple of the airline training experience. The DAL accident pointed out that even with this new awareness across the industry, sometimes Mother Nature just is going to have her way. But the longer term safety record proves the essence of constructive inquiry based on known facts, and the willingness, at the time, of the industry to look inward to achieve the most essential goal whatever the cost.