We’re Stuck With The Senate. What Then?

As a followup to 'Fools, Drunks, and the United States of America,' a triage guide to possible steps in defending democracy.

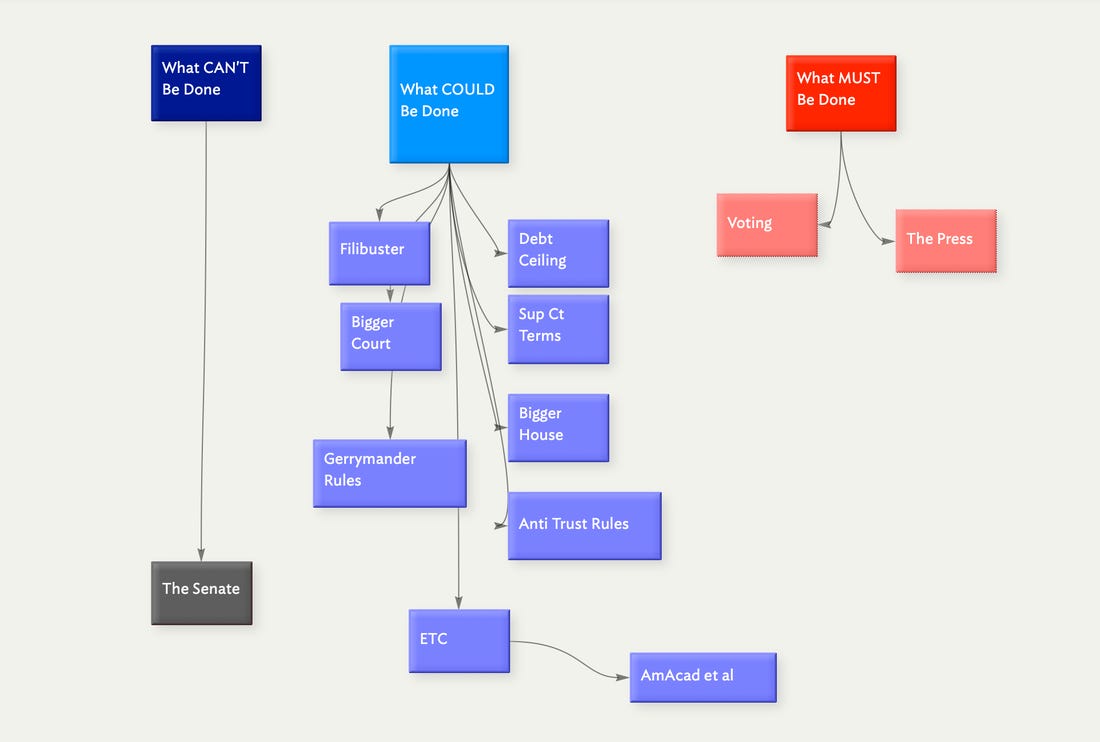

This post is the typed-out version of a white board. In fact, the white board-like image down below is what I have in mind as I write.

The power of a white board is to help you lay out, connect, and classify a range of items—and then concentrate on a few without losing track of the rest. That is the idea here. This post is an initial followup to “Fools, Drunks, and the United States of America” and aims to categorize ways Americans could think about improving our now badly flawed rules for democracy.

The argument in the previous post was that the United States is blessed by its society—and its location and resources and other advantages—but cursed by its form of governance:

— It has the advantage of the world’s most creative, self-renewing, highly adaptive, and highly diverse large-scale group of citizens and communities.

— Who labor under the disadvantage of some of the world’s most rigid and outdated rules of national governance. These rules are too hard to change (though not impossible, as we’ll see below), and too easy to abuse (as recent history has shown).

A global cliche is that America is a “young” nation—which is true if you judge by median population age, relative to other rich countries or big economies. (The difference is due to immigration.)

But in its governing system, the United States is geriatric. Its rules of Constitutional operation were set down when George III was on the throne in England, Catherine the Great in Russia, and the Tokugawa shoguns in Japan.

The Constitutional accords were a compromise toward a form of democracy for the late 1700s, when millions were enslaved and only white males could vote. As I argued last time, these 18th-century agreements have grown so mis-matched to the realities of large, modern 21st-century America that they are effectively anti-democratic, and have skewed the system’s balance from protecting “minority rights” to enshrining “minority rule.”

What can the U.S. do about it? Let’s run through the elements on the white board. I’ll list items in two major headings, setting markers for later discussion. Then I’ll mention the group that is truly urgent, and for which I and my colleagues in the press share major responsibility.

The columns on the white board are: What can’t happen, what could happen, and what must happen—even within the constraint of antique rules. Each of the specific points will seem obvious, but for me it concentrates the mind to see them in one place.

I. What Can’t Be Fixed: The Senate

The two-senator-per-state bargain was made in a very different America. Our America is stuck with it.

As pointed out in the previous post, much of the intellectual guidance behind The Federalist Papers and ultimately the Constitution came from “big-state” figures. Notably James Madison of Virginia, and Alexander Hamilton and John Jay of New York.

Under the circumstances of those times, when big states like theirs had “only” ten times the population of the smallest ones, the art-of-the-possible in the Constitutional Convention led to the two-senators-apiece arrangement, for the original 13 states. Now there’s a seventy-to-one population gap between most and least populous of our 50 states. But they all have equal “Suffrage” in the Senate, which can’t be changed.

Why? Because of the last line in Article V of the Constitution:

No State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

OK.

But fortunately, that is pretty much it, for the no-go list.

II. What Could Be Fixed: Quite A Lot.

Most items in this category are not “likely” to happen, and simply will not happen without concerted political effort. Their significance here is that as a legal and Constitutional matter they could happen—and if they did, they would re-set the American balance toward democratic functionality.

For now my goal is to itemize rather than explain or fully argue them. I’ll mention an indispensable resource on Constitutionally acceptable ways to bolster American democracy. That is Our Common Purpose, a report from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences last year. I hardly ever recommend actually reading commission reports. This one is excellent and will change your view of each day’s news. (A shorter, breezier, funnier counterpart is a book I’ve mentioned before: Thomas Geoghegan’s new The History of Democracy Has Yet to be Written.)

Here goes, starting with the most feasible.

1. End the filibuster.

Everybody has heard about the filibuster. Not many people understand how much legitimacy the Constitution gives it, which is zero. Nor how recent its most abusively anti-democratic effects have been. It has kicked in with a vengeance only in the past twenty years.

For more you can go to this informative brief history by Sarah Blinder from 2010, or several more published this year: Adam Jentleson’s book Kill Switch, or an exchange between Al Franken and Norm Ornstein, or an explainer by Philip Bump in The Washington Post.

Bump offers this useful summary:

The Senate is already an institution that distributes power unevenly. States that make up only 16 percent of the country’s population cumulatively are represented by 50 senators, half of the total. Reduce the bar to 41 senators [which is all it takes to stop a bill via filibuster] and you’re talking about just under 11 percent of the population. Meaning that senators representing a bit over one-10th of the country could block any legislation from passing.

I know all the counter-arguments here. I know the two magic names of the moment: Manchin and Sinema. The point is, as a legal matter, returning to “original intent” by removing the filibuster would be the quickest, cleanest step away from anti-democratic governance.

2. Eliminate the debt ceiling.

I wrote extensively about this earlier this fall. For instance here, here, here, and here. The summary is: the whole idea of a “debt ceiling” is preposterous, since it boils down to a threat not to pay out money that Congress has already voted to spend. Its role in public life is purely obstructive and destructive.

Congress could permanently end this charade with a vote.

3. Set fixed terms for the Supreme Court.

I never thought the word tontine would be so useful in explaining American dysfunction. A tontine is a ghoulish arrangement by which members of a group all pay in money, and then whoever dies last rakes in the proceeds. For what it’s worth, it’s named for the man who came up with the concept, a 17th century Italian banker named Tonti

All right: staffing the modern Supreme Court is not exactly a tontine. But it resembles it in the outsized role of luck and brute actuarial factors. That the Court now has a solid 6-3 Republican majority, rather than 5-4 the other way, is largely due to the combined efforts of the Grim Reaper, and Mitch McConnell.1 Accidents of life span have mattered in all forms of governance, from Alexander the Great’s short-lived empire onward. But they’re not supposed to be built into the structure of a democracy.

A sane answer would be fixed 18-year terms for members of the Supreme Court. Each president would foreseeably have one appointment every two years. Parties wouldn’t have to go scrounging for the youngest plausible (but ideologically dependable) nominee, in hopes of maximum shelf-life on the Court.

For more on the advantages of this approach, and why it’s perfectly consistent with the Constitutional stipulation of life service for federal judges, check out the American Academy report. Here’s their summary of the relevant part:

RECOMMENDATION 1.8

Establish, through federal legislation, eighteen-year terms for Supreme Court justices with appointments staggered such that one nomination comes up during each term of Congress. At the end of their term, justices will transition to an appeals court or, if they choose, to senior status for the remainder of their life tenure, which would allow them to determine how much time they spend hearing cases on an appeals court.

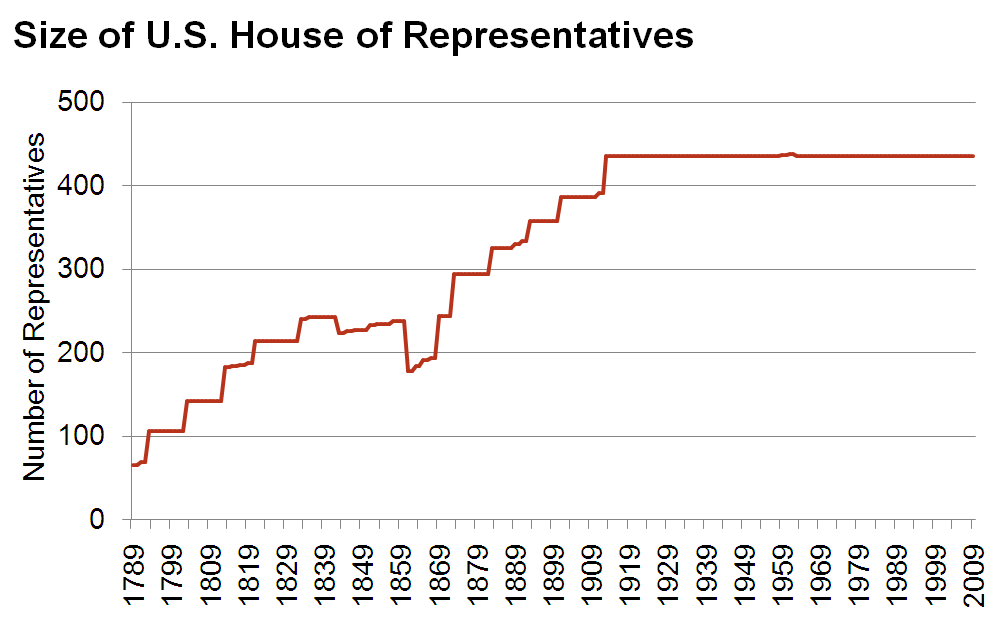

4. Expand the House of Representatives.

For the full rationale, please check the previous post. This chart tells much of the story:

Keeping the House growing would match the founder’s “original intent.” Again, Congress could do this, with no Constitutional complication. (Update: the Washington Post has a good op-ed on expanding the House, by Lee Drutman and Yuval Levin, here.)

5. Expand the Courts, including the Supreme Court.

I’m listing this rather than fully explaining it. See the most recent version of the case, made today in the Washington Post by Laurence Tribe and Nancy Gertner. Here is the heart of their argument, based on a partisan Court’s recent rulings about voting rights, gerrymandering, money-in-politics, church-state relations, and abortion:

Those judicial decisions haven’t been just wrong; they put the court — and, more important, our entire system of government — on a one-way trip from a defective but still hopeful democracy toward a system in which the few corruptly govern the many, something between autocracy and oligarchy….

Worse, measures the court has enabled will fundamentally change the court and the law for decades. They operate to entrench the power of one political party: constricting the vote, denying fair access to the ballot to people of color and other minorities, and allowing legislative district lines to be drawn that exacerbate demographic differences. As a result, the usual ebb and flow that once tended to occur with succeeding elections is stalling.

A Supreme Court that has been effectively packed by one party will remain packed into the indefinite future, with serious consequences to our democracy.

Assess the argument for yourself; I agree with it. Also see this post by George Tyler. Again the point is, these are changes the Congress could make on its own, rather than requiring any Constitutional change.

6. through 999… : Lots of other possibilities.

There is a lot more repair that could be done within Constitutional rules. Again a few samples from the American Academy summary page:

RECOMMENDATION 1.2

Introduce ranked-choice voting in presidential, congressional, and state elections…

RECOMMENDATION 1.4

Support adoption, through state legislation, of independent citizen-redistricting commissions in all fifty states….

RECOMMENDATION 5.2

Through state and/or federal legislation, subsidize innovation to reinvent the public functions that social media have displaced: for instance, with a tax on digital advertising that could be deployed in a public media fund that would support experimental approaches to public social media platforms as well as local and regional investigative journalism…

RECOMMENDATION 5.4

Through federal legislation and regulation, require of digital platform companies: interoperability (like railroad-track gauges), data portability, and data openness.

There’s a long list more—from this report and many others. Constitutionally acceptable (and fiscally modest) ways to bolster independent local journalism. Anti-trust enforcement that suits the technological and business realities of these days. Anyone who has thought about public life, or spent a day living in America, will have a list of other ideas, covering health care to law enforcement to education. A central thrust of Deb’s and my Our Towns work has been the abundance of reform ideas being tried, tested, and improved day by day across the country.

Here is the point: democracy could be repaired, even under today’s outdated rules. That is worth bearing in mind, while fighting the emergencies I’m about to mention.

III. What Must Be Fixed: Elections Themselves, and the Press

Category I is what we can’t do. Category II is what we could. Category III on the white board includes the two house-burning-down emergencies, which should be the focus of citizen action and of the press right now.

The first emergency is the shift by one political party from indirect pressure on democracy—through court appointments, the filibuster, gerrymandering, '“dark money,” the sad list of familiar issues—to direct outright sabotage of the democratic transition-of-power itself.

The oblique assaults, from Shelby County to Citizens United, were bad enough. The application of violence on January 6, and its de facto acceptance by one party’s leadership, is something new and much worse.

That is the significance of Donald Trump’s “Stop the Steal” lies. It is the even-greater significance of nearly all of the Republican House and Senate delegation acquiescing to him. It is the significance of Republican boycotts of the Congressional commission investigating the insurrection. And of all the state-wide Republican efforts to interfere with elections that Barton Gellman has dramatically laid out in his new Atlantic cover story. And other unfolding news each day.

The second emergency is the abject failure of much of the mainstream press to reflect this changed reality.

This has been so much my topic in the 25-plus years since the original Breaking the News was published that I’m not going to do more right now than highlight this item on the dashboard. By the way, the title of that book, in 1996, was How the Media Undermine American Democracy. I had not meant it as a manual.

Every time my colleagues in the media shrink from using words like “coup” or “lie,” we undermine democracy. Every time we present defiance of legal obligations, whether Congressional subpoenas or court requests for documents, as a “shrewd” or “daring” political move, we undermine the power of legal order. Every time a TV talk show “balances” a panel by inviting on politicians who voted against certifying presidential election results, it validates their contempt for elections and democratic choice. Every time we present hostage-taking measures in the Congress—like debt-ceiling threats or willful one-Senator “holds” on important nominations—as plays in a “game of chess” (or “chicken”), we undermine hopes for governance as more than a game. Every time we switch from one hyped crisis to the next, we undermine belief in our public ability to cope with any threat, or recognize real crises.

This has also been the theme of a corps of journalists I frequently refer to. Dan Froomkin gives a recent illustration here. And Jon Alter, a long-time friend and the author of a recent great biography of Jimmy Carter, made the argument this week for a fundamental change in the press’s sense of urgency:

Much of the mainstream media remains trapped in a 20th century paradigm, where truth is often subordinated to phony balance and an evasion of critical issues in favor of chasing ratings. Meanwhile, rightwing media is no longer a scrappy insurgent… but the dominant source of “news” and poisonous lies for nearly half the country.

For what’s left of the mainstream media, the paradigm is the problem.

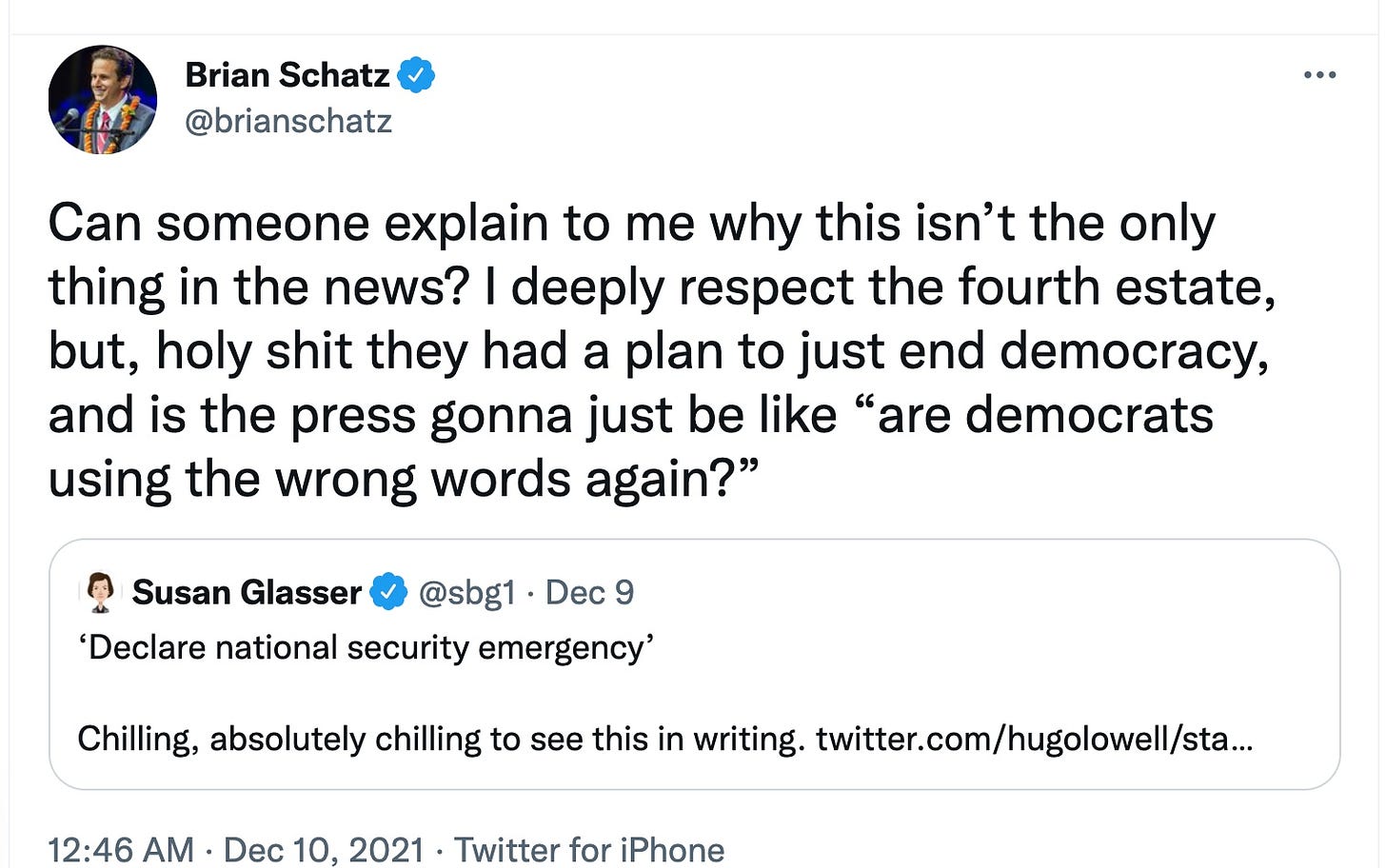

A serving U.S. Senator, Brian Schatz of Hawaii, made a similar point:

It’s up to all of us, not just the press. But those of us protected by the First Amendment have a special responsibility. Our duty is clear.

More to come on this theme. I have it on the white board.

To distill the familiar story into its tontine elements:

—After Antonin Scalia died in 2016, McConnell refused to consider Merrick Garland’s nomination through the remaining 10 months of Barack Obama’s term. This gave us Justice Neil Gorsuch, age 49 when sworn in.

—Then in 2018 Anthony Kennedy decided to retire while Donald Trump would have a chance to name his successor. This gave us Justice Brett Kavanaugh, at age 53.

—And when Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in 2020, having rebuffed Barack Obama’s suggestion years earlier that she retire while he could name her successor, Mitch McConnell rammed through a third Trump nomination in the six weeks before the Trump-Biden election. This gave us Justice Amy Coney Barrett, age 48 when confirmed.

Different medical facts, different personal decisions, leading to a completely different balance on the court. Now the political world must follow Stephen Breyer’s health and belief in his own indispensability.

This is how monarchies are supposed to work, not democracies.

Two comments regarding the Senate.

1. While it is "unfair" that small states get the same number of Senators as large states, I don't see it having any effect on our government. Most people point to the partisan bias of the two-senator small state bias but that in fact is incorrect. Actually, the smaller states are balanced by party. Currently, the ten smallest states have 10 Republican and 10 Democratic (or Democratic-caucusing) Senators. That balance has been maintained pretty much for the past twenty years or so. In addition, it's not clear to me that small states hold unfair leverage which they use for small state concerns. Are we passing legislation that is unfairly biased toward Vermont versus California, or Wyoming versus Texas? Not that I'm aware of. The divisions are partisan and national, not local and based on state size.

2. Nonetheless, the Senate is a problem and creates unnecessary obstacles for effective government. But I believe we can -- effectively -- get rid of the Senate, despite what you cite in part 1. And we can do that by giving each state equal suffrage in the Senate -- i.e., *none.* Each Senator would have a zero, or non-binding, vote in areas we choose. We could make the Senate more like the House of Lords, with something of an advisory role but with limited or no ability to block (or pass) legislation. We could consider retaining certain areas where Senators have an effective vote, such as for treaties and some (if not all) appointments. But for legislation? Nope, nothing.

That would seem to pass constitutional muster to me, even if it would demand a constitutional amendment for it to happen.

from Joseph Britt: " The task before us today is primarily a moral one, only very secondarily one of institutional reform. I would rather it were one we did not face, but as we Americans have gotten ourselves into this fix it will be up to us to move out of it, and forward." (posting at twitter about the above article)

It is all only moral, and ethical. That is the only important thing. The Politicians with a capital P who are our leadership in the communities, where the voters live, have to look at themselves in the mirror if they are not truthtelling. We have a complicated Senator, Senator Susan Collins, who is a lot deeper than non-Mainers know. This is not the person portrayed on SNL. There is a long tradition of independent thinking in Maine, maybe because we are stuck out there at the end of the country, all alone. People leave us alone, or used to. Senator Collins grew up in the far north, she is not easily scared by a bear in the back yard or a crowd of R in the Senate Chamber. Senator Olympia Snowe, and other current and past politicians in Maine do have common ground in many ways. Look to R and D crossing the aisle out of sight of the media, a la how to Get to Yes, an important Harvard U Mediation Project initiative. The 24/7 news cycle destroys morality by rushing to get more content which is then diluted into something called "cuisinart journalism." Great article, thank u!