This is another post about the travails of the media. It will start with some old questions, build to some new ones, and end with an area where I’m revising some of my longest-held views. And asking for advice.

I’ll begin with a book I’ve just bought and read, Margaret Sullivan’s Newsroom Confidential.

I’ve written many times about Margaret Sullivan. She is a former editor of the Buffalo News, a former excellent public editor for the NYT and media columnist for The Washington Post, and now a visiting professor at Duke.

While shifting to academe she has published several “What I have learned” reflections on her time in the business. They include this farewell column for the Post; a Post Magazine article on how not to cover Donald Trump in any future race; and the new book.

The book is interesting and valuable for people inside and outside the journalism business. I mention it now because of a nugget near the end. Sullivan says that at the Post “I joked with my colleagues that there were really only five possible media columns, and I would write aspects of them over and over”:

“There was the ‘Evils of Facebook’ column; the one about the tragedy of local newspapers’ decline at the hands of hedge-fund owners; the Fox News damage-to-society column; the ‘don’t magnify political lies’ column; and the one about the mainstream media’s intransigent flaws.”

Boy, do I know what she means.

In a way, the cycle-of-predictability she mentions is a sign of the importance of these classic themes, rather than of failures of imagination. Think of the parallels in other realms: There are really only five possible movie plot lines. Boy meets girl. And then... There are at most five ongoing narratives in U.S. political history. Outsiders take power, to redress grievances. And then … There may not be even five master narratives in world religions. People suffer. But then …

I’ve written variants on all the articles Sullivan mentions, starting before either Facebook or Fox News existed. My book Breaking the News1 came out when Mark Zuckerberg was in sixth grade and shortly before Fox News went on the air. Many of the people I’ve mentioned admiringly on this site, for instance in this homage to the late Eric Boehlert, have, like Sullivan, done the media-critic version of a jazz musician’s riffs in a number of familiar chords.

You can go back much further than that. Almost 40 years ago Neil Postman wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death. More than 60 years ago Newton Minow gave his “television as vast wasteland” address. Seventy-five years ago the “Hutchins Commission” delivered its major report on freedom of the press. Exactly 100 years ago Walter Lippmann wrote his prescient book Public Opinion, about the impossibility of getting an “objective” view of things we don’t experience ourselves. Nearly all of them stand up surprisingly well.

You can keep going back and back. But Margaret Sullivan’s line came while I have been thinking about a sixth media story line. That is the one called what comes next?

The back story, part 1.

I’ll return to my book Breaking the News. You can see an Atlantic cover-story excerpt from 1996 here.

Many themes in the book obviously connect the press-criticism of that era with what makes people yell at their TVs or Tweet “cancel my subscription!” these days. Some similarities:

-The mainstream press obsession with politics over anything else. (“Martians land on Earth. Here’s what it means for the midterms.”)

-The parallel obsession with prediction. (“Martian sworn in as President. What does it mean for the midterms?”)

-The belief that “truth” lies midway between two sides—however dissimilar those positions might be. (“Martians dine on human beings. Mars spokesman says, We invited them ‘for dinner.’ ”)

-The eye-rolling boredom with anything “positive” or “constructive.” (Today no Martians ate people. Where’s the news in that?) You know all the rest.

What I realized in reading Newsroom Confidential was another strong premise of my long-ago book: That the press’s framing of reality mattered.

The media’s failures weren’t just a niche issue. They affected every other part of society. The subtitle of the book was “How the Media Undermine American Democracy.” The argument was that if people ended up viewing public life as merely one more reality-TV show, but with less photogenic stars, they’d be less engaged and even more despairing than actual reality called for.

Back story part 2: the ‘Our Towns’ corollary.

I realize, too, in retrospect, the connection to the Our Towns work that Deb Fallows and I have done in the past decade. This was through our hundreds of web posts, our book, our HBO movie, and our new local-reporting foundation. At one level, we’ve mainly been reporting on what has been happening, beyond mainstream-media notice, in places from Eastport, Maine, to Muncie, Indiana.

But our argument was not just that significant things were underway. It was also that national media’s lack of interest and reporting on these developments (versus clichéd “guy in a diner” stories) mattered. Here is how I put it in the first chapter of that book, after our years on the road:

By the end of the journey, we felt sure of something we had suspected at the beginning: that an important part of the face of modern America has slipped from people’s view, in a way that makes a big and destructive difference in the country’s public and economic life…

Because many people don’t know [what they’re not reading, about city-by-city reinvention], they’re inclined to view any local problems as symptoms of wider disasters, and to dismiss local successes as fortunate anomalies. They feel even angrier about the country’s challenges than they should, and more fatalistic about the prospects of dealing with them.

That was in 2018. I contend that even in 2022 this is not some nutso outlier view. A Gallup Poll just last month found that 85 percent of Americans were “satisfied” with their personal lives, and by extension their community lives—even though roughly the same proportion, 85%, were downcast about the country as a whole.

There’s a lot going on with these numbers. My point for the moment is how different this poll is from what you would infer from standard daily news. (“Despair over rising prices at the pump.”)

Part 3: National media trying to change the narrative.

I have been keeping an ever-growing list of examples of the national press trying to present reality in full perspective.

I’ll give just one recent illustration. It was the program lineup on CBS Sunday Morning one week ago ago, with several segments all focused on American divisions but presenting the world as something more complex than a Red-v-Blue death match. A few of its segments:

—Our friend John Dickerson, talking with Jon Grinspan, of the Smithsonian, on how the political and social divisions of these days are similar to, and different from, those of previous centuries.

—Longtime newsman Ted Koppel on something we’ve covered extensively: the revolution in trade-school training and certificates, and the burgeoning opportunities in high-wage, skilled-trade jobs. At the end of the segment, Koppel delves into “what does this mean for the midterms?” territory, but it’s an enlightening segment.

—Ben Tracy on the economic and cultural tensions in attractive places where people with money are choosing to live—in this case, Jackson, Wyoming. It’s a three-dimensional portrayal—tough and critical, but nuanced and more realistic—rather than normal “diner” reportage.

Check it out.

Part 4: National media going the other way.

I also have a bigger list of national-media stories that re-illustrate the problems people (including me) have been talking about for years. Some recent instances:

A front-page story in the New York Times assessing the transport of Venezuelan refugees from Texas, through Florida, to Martha’s Vineyard largely as a political chess game between two GOP governors. Who has read the mood of his party more accurately and played the game more shrewdly? Greg Abbott of Texas? Or Ron DeSantis of Florida? This is not a question that would occur to most people outside the political-journalism world.

Another story in the NYT about how “dysfunction” in the US Senate has made it a less attractive career choice for ambitious politicians—despite the evidence of people who seemingly will do anything to hold onto a seat. The story does not include the word “filibuster,” nor any reference to Senators’ changing positions on the January 6 attacks. The narrative is of a disembodied, “no one’s to blame” institutional failure. Notice how rarely you see that kind of “dysfunction just happened” presentation from a leading paper on other topics — business, technology, the arts, most global affairs, etc — and how frequently you do about U.S politics.

Much greater coverage of the parts of the economy that are bad (inflation) than of the parts that have been good (job growth)—followed by stories on why Americans “feel worse” about the economy than mere numbers would indicate.

Stories on how Herschel Walker “beat expectations” in his Georgia Senate debate, against incumbent Raphael Warnock—as if this were a sports-betting “beating the spread” question, not a display of a candidate’s incoherence and dishonesty. And so on.

Back story part 5: changing my mind?

Here is where I am going: I am learning to accept that our mainstream media will not adapt to the needs of this moment in our public life. Having talked and written about institutional bias of this sort for many decades, I am beginning now to accept that the central institutions are not going to change. This is how it is going to be. I don’t need to keep pointing this out.

I now believe that the national press cannot properly adapt or respond to the realities of our Trump/Facebook times.2 Its leaders seem too dug-in and defensive. It’s how they’re wired. The more barbs they get from the likes of the brilliant “New York Times PitchBot” on Twitter, the more certain they seem that they are doing the right thing.

The slim silver lining is perhaps it no longer matters as much how the once-dominant, once-mainstream news outlets frame our political reality.

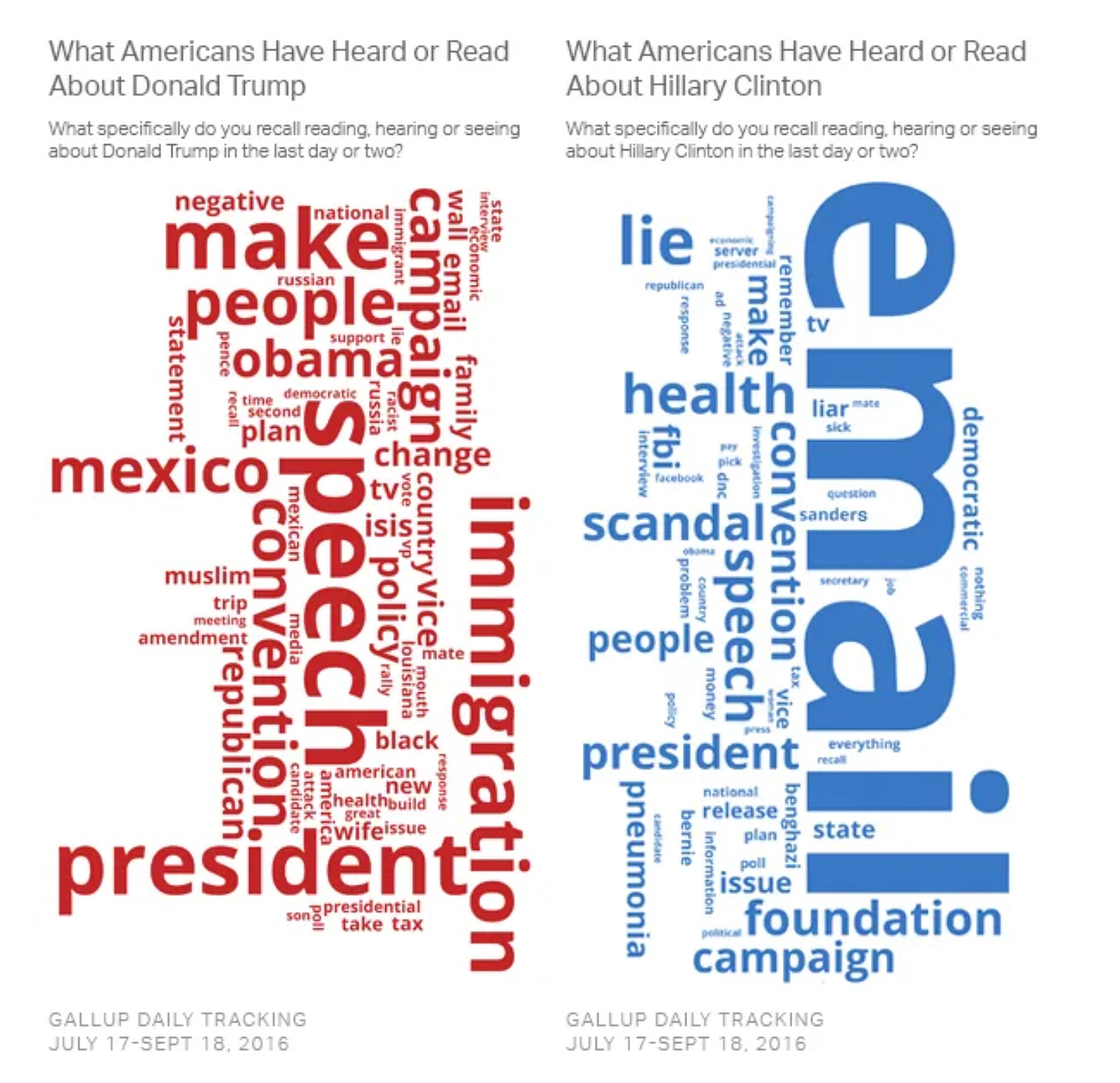

I think it mattered, beyond question, that the most influential mainstream media covered the 2016 election the way they did—as captured in this famous info-graphic from the Gallup organization:

It mattered, back then, because saturation coverage from “real” news outlets normalized the idea that the Trump-Clinton choice was a toss-up in terms of ethics and morality. It was “both-sides-ism” in its purest form.

But as info-spheres have fragmented, could any big-media tic still matter as much as that coverage did? I don’t know. But I think we’re going to see all the same tics, from all the same players, for a long time. And in a world that includes Marjorie Taylor Greene, Tucker Carlson, Kanye West, and other powerful mis-informers domestic and foreign, the quirks of big media are very far from the main crisis in public awareness.

Which leads us to …

Part 6: The caravan moves on.

Here is a related part of Margaret Sullivan’s book:

Big Journalism is notoriously bad at looking, in an open-minded way and without defensiveness, at what has gone wrong.

If top editors were good at such things, we would have heard a lot more about the extreme overcoverage of Hillary Clinton’s email practices and a lot more about how this can never happen again…

Can an abundance of high-quality, mission-driven journalism overcome misinformation and break through to those indoctrinated in an alternative reality?…

I have serious doubts.

I do too.

So the next chapter is … ?

Margaret Sullivan has some proposals in her book. So do scores of other organizations and people all scrambling to create a different news ecosystem to replace what seems unchangeable in our current one. So will I, upcoming, in this space.

Significantly, nearly all of these ideas involve less of what Margaret Sullivan has being doing in her columns, and what I have done over the decades, and what many others have emphasized as well: pointing out what is not working in the current media models.

-That seems less and less worth it.

-If critiques were going to stop “both-sides-ism,” that would already have occurred.

Instead these ideas involve much more emphasis on building something new. Devising new public-information systems, attuned to the social, political, economic, and technological realities of our times. Finding a new, viable, sustainable model for the oldest function in journalism: that of creating community by covering local news. Building, inventing, experimenting, adapting. Behaving like a network of entrepreneurs rather than of critics. Working around the old system, rather than trying to change it.

That’s the sixth media story. What comes next. Watch this space—and many others — for more.

I always note that this book and some others I did at Pantheon were edited by the great Linda Healey.

Before anyone points it out. The depth, breadth, and specific data now available in the press in the largest sense are all improving constantly. More than once I’ve taken a coast-to-coast airline trip on a Sunday, equipped with the Sunday editions of the NYT and the WaPo—then spent the entire trip reading superb and varied reporting.

I cant't help but think that if you are seeing the same patterns again and again, that indicates two things (well, at least 2 to start.)

One is that this is evidence of some fundamental constants in the world of journalism that are inherent to the basic assumptions it operates on, some of which may not be apparent to or even recognized by the people cranking it around every day.

The second is that to get a different result may require finding a way to modify those assumptions, or discover how to change the conditions under which they apply. Are the constraints you see common to other cultures, other ways of communicating stories to a mass audience, or what?

I'd make a guess Kauffman's Rules cover this in some way.

One further prescient text to cite is my late brother Mike Janeway’s book, The Republic of Denial, whose thesis 30 years ago was that the entertainment industry success in taking over journalism was a step towards its taking over Politics. Bill Janeway