The Powers That Were

American institutions, for all their flaws, have protected our people. Now the institutions need our help.

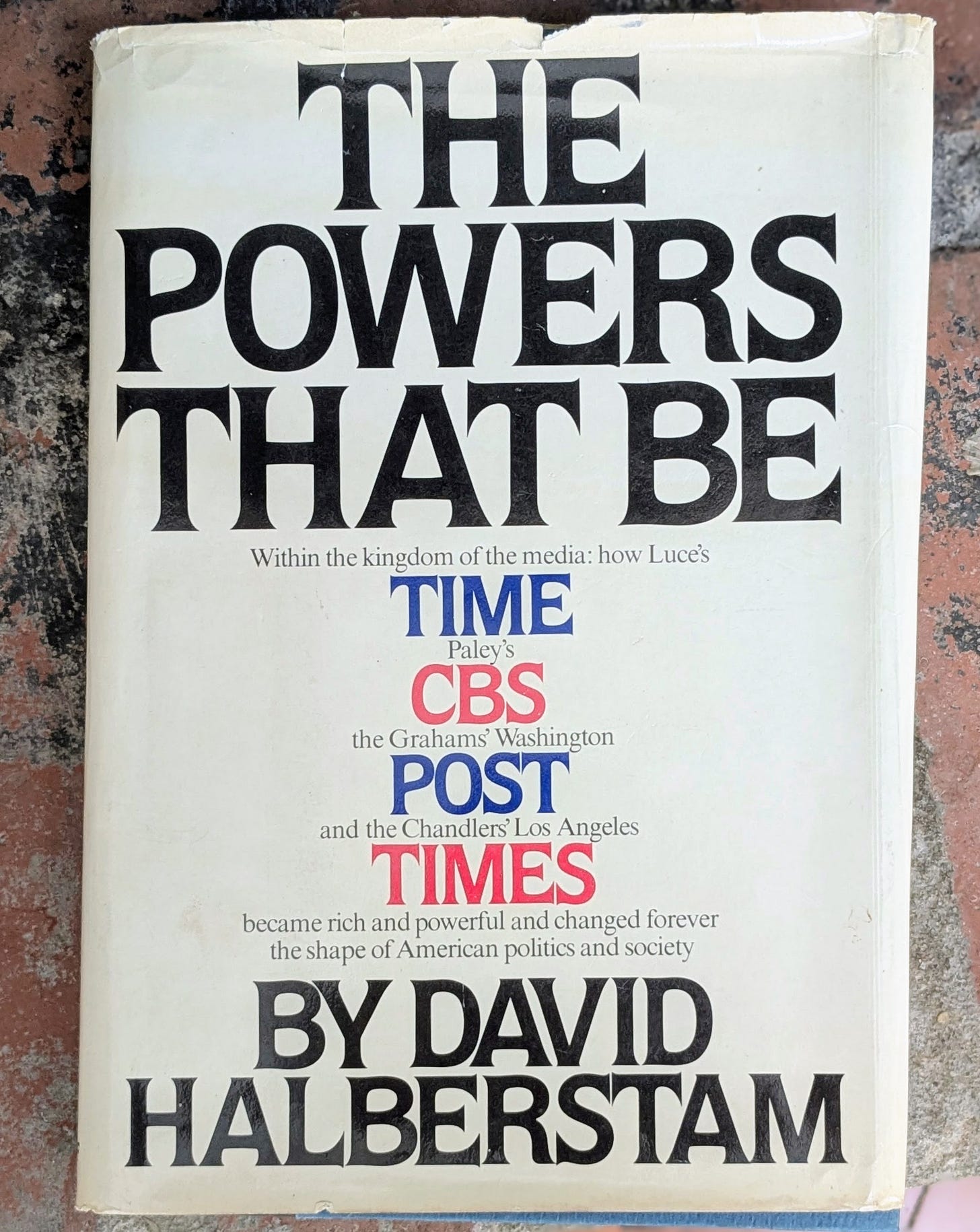

Shown in July, 2025, in California, a book I bought in Washington DC back in May, 1979.

This week, as a part of a packing and clean-up drill, I came across a book I hadn’t looked at in decades. It’s the one above, shown in its well-thumbed actuality.

It’s a book I’ll keep—David Halberstam’s 700-page The Powers That Be, published in 1979. I mention it now because, for me, happening to see it at this moment helped crystallize a point about today’s US emergencies.

The point is simply this: That the real crisis in the US of this Trump era is institutional. And that the most urgent object of civic patriotism in our times is to shore up the institutions whose vulnerabilities the Trump era has revealed, and exploited.

The democratic system, for all its well-known flaws, was intended to protect the people, and largely has. Now people need to save the system.

What our institutions were supposed to protect us from.

Here’s some context, on why institutional failure connects so much else that is going wrong.

—We know we have a problem of leadership pathology. Everything that could be wrong with a human being, is wrong with Donald Trump.

As it happens, both of Trump’s parents turned out to be long-lived, although his father spent his final years in dementia, with first symptoms at about Donald Trump’s current age.1 Donald Trump is not all there, but actuarially he will likely be with us for a while. And behind him stand JD Vance, Stephen Miller, Russell Vought, Emil Bove, and others who share his amoral cruelty.

—We know we have a crisis of disinformation, misinformation, and simple info-chaos. Neil Postman, who sadly was less long-lived than the Trumps, presaged our situation with the brilliant Amusing Ourselves to Death back in 1985.

—We know that we have “culture war” problems, because we read and hear about them nonstop. And we hear almost as frequently about today’s political messaging imbalance: Voters don’t like what Republicans actually do in office—tariffs, Medicaid cuts, abortion bans, and so on—yet they seem to like the Democratic “brand” even less. And we know we have gerrymandering and vote-suppression problems, now openly egged-on by Trump.

But connecting all these, and now looming largest to me, is the weakness that Trump and his operatives have revealed in the institutional infrastructure of US governance.

Americans love to say that our constitutional rules, and our brilliant checks-and-balances structure, are what make the nation so strong. I’ve long believed just the opposite: That the US governing structure is flawed and outdated. (Worth remembering: Of the hundred-plus new democracies that have emerged in the past century, exactly zero have copied the US governance model.) And that only good luck, plus natural advantages—location, resources, scale—plus some filament of shame and self-restraint, have kept the US going as well as it has. We’ve succeeded in spite of our system, not because of it.

We’ve relied on that tiny thread of shame and self-restraint even from the Huey Longs, the Joe McCarthys, the Strom Thurmonds. On that respect for norms shown even by Richard Nixon, who finally resigned rather than be hauled out in disgrace.

Now we’ve seen what happens when that filament is gone.

The powers that (used to) be.

What’s the connection to David Halberstam and this old book? It starts with the book’s cover.

When Powers That Be came out, Halberstam was in his mid-40s and had six other books behind him, plus a Pulitzer prize for his reporting from Vietnam. His specialty was presenting big, panoramic issues through vivid individual tales—what we’d call these days a “Michael Lewis book.”

The most famed of Halberstam’s “ big books” remains The Best and the Brightest, published in 1972, on how the brainiacs of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations walked into the disaster of Vietnam. When Errol Morris’s 2003 documentary The Fog of War came out, I thought of it as essentially Robert McNamara’s decades-later response to Best and the Brightest. Halberstam’s book had that much impact.2

Halberstam’s next big book was The Powers That Be. Similarly it presented a huge theme—what was right, and wrong, with the American press—through a series of interlocking sagas. And much as Best and the Brightest had been about the life-and-death effects of hubris—how could people so smart, do something so dumb?—The Powers That Be was about the dangers mainstream media companies were facing precisely because they were so rich and influential.

The four seemingly impregnable 20th century US media empires—sources of wealth, shapers of opinion, organizations that “changed forever the shape of American politics and society”—were those on the cover.

Time magazine, from founder Henry Luce onward.

CBS News, its culture shaped by reporters like Edward R. Murrow and his successors, its business honed by William Paley.

The Washington Post, which rose from local to global influence under Ben Bradlee as executive editor, Woodward and Bernstein and countless others as reporters, and Katharine Graham as unexpected publisher (after her husband’s death) and inspirational leader.

The Los Angeles Times, which under the Chandler family grew in business success and journalistic influence far beyond its California base.

Halberstam was not reverent about these figures or their institutions. He talked about tensions we’d find familiar from current press-and-politics news. For instance: How the LA Times had essentially made Richard Nixon’s career, through its right-wing influence in post-World War II Southern California. How Henry Luce wielded Time Inc’s power for his political causes, notably for the “China lobby” that urged support for Chiang Kaishek’s Taiwan. How all of these media institutions went through internal battles about what we’d now call the “clickbait” problem: How to balance news and entertainment, how to hold people’s interest while keeping them informed. How carefully all the organizations considered when, and on what issues, they dared openly defy a sitting president or other powerful officials.

But what is most immediately striking, as we look at this 1979 list in 2025? Why did I look at the cover in amazement as I pulled it off a shelf?

It is the Ozymandias precision of those four mentions. Exactly the institutions that once epitomized business success and political power now are shorthands for what has been lost.

Time magazine, a shell of its previous existence. Trump’s obsession with being its “Man of the Year,” including having a fake “Man of the Year” issue displayed in his country clubs, is one more token of his frozen-in-the-1980s general world view sensibility.

CBS News, so timorous that South Park is mocking it.

The Washington Post, making the world wish that MacKenzie Scott, rather than her first husband, were now its owner.

The Los Angeles Times, enfeebled by one billionaire (Sam Zell) and then mismanaged by another (Patrick Soon-Shiong), serving as a reminder of the perils of plutocrats as publishers.

The best-known line of Ozymandias is:

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

The next three lines, less frequently quoted, are equally apt:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

These were the institutions that, while making at times huge profits, also thought their purpose included defending the democratic system when it came under assault.

Now? Facebook/Meta? TikTok or Xitter? Amazon or OpenAI? Apple or Microsoft?

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The institutional countdown.

The point of the list above is how profoundly the media institutions on which the US system depended could go away. In lightning-round style, let’s do a countdown of others:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Breaking the News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.