I’ve spent the past 24 hours immersed in the world of small-plane flying, one of my passions over the decades. In several books—Free Flight, China Airborne, and Our Towns—I’ve discussed the never-tiring fascination of seeing life from 2500 feet up, and of comprehending at a glance the logic of landscape and settlement. Why towns are built by rivers or waterfalls; what features are concealed at ground level but all too evident from above.

An underrated virtue of the aviation culture is the way people maintain their ability to take part in it. I’m not talking just about professional pilots, the ones in the front seats of airline flights. They are overall amazingly skilled. But a spillover of what makes them so safe and competent applies even to amateurs like me. That is modern aviation’s insistence on continuing to show that you can participate.

Imagine if you had to retake a driver’s-license test every few months. Or if academic or judicial tenure came with the proviso that you present a tenure-worthy argument at regular intervals. That is in essence the logic of modern aviation. Pilot certificates in principle last your whole lifetime. But to continue “exercising their privileges” you have to keep re-qualifying.

—For the aviation professionals, that means continually demonstrating their fitness and competence. Health checks, simulator drills, “what if?” exercises about emergencies most of them will never encounter in real life. But if they did…

—The version for amateurs is an array of “currency” standards and competence checks. Again, health and vision and hearing exams. Regular “flight reviews.” Currency standards for special conditions—for instance, landing at night with a passenger aboard, or flying in the clouds on an “instrument plan.”

For amateurs, enforcing these standards is mainly left to the insurance industry. Usually no one from the FAA is going to check your certificate or qualifications. In 25 years it’s never happened to me. But to get insurance, you have to swear that you’ve met chapter-and-verse of the legal requirements. And if anything goes wrong, you know the insurance companies will check.

The stricture that looms large in my aviation life is the “instrument currency” requirement. To get insurance at any reasonable rate, especially as a “veteran” pilot, you need to take regular IPCs, or Instrument Proficiency Checkrides. These involve showing that you could safely fly the plane in bad conditions—in unexpected weather, with equipment failures—even if, in practice, you try your best to avoid those conditions.

No torrential rains. No overwhelming winds. So, it’s time for a check flight.

That is what I was doing today. I was going to do it yesterday, but gale-force Santa Ana winds across inland Southern California led to severe turbulence. I was going to do it two weeks ago, but the historic California rains washed out those flights, and even swamped our tied-down little plane, leading to just-completed repairs (to remove traces of the muddy runoff water from the wheel bearings and brakes).

So today the skies were clear and the winds were mild. And—to get to the point—here are three screenshots and linked animations from FlightAware of what was involved.

My hope in each case is that the screenshot image will give an idea of what I found interesting. To see a quick animation of what such flights look like, you can click on the link in the caption of each screen shot and then hit the “Replay” button. I think they’re best at what FlightAware calls “10x” speed, which in fact compresses each flight into about 30 seconds.

1. Santa Barbara to Santa Maria: ‘Back-course’ and ‘missed approach hold.’

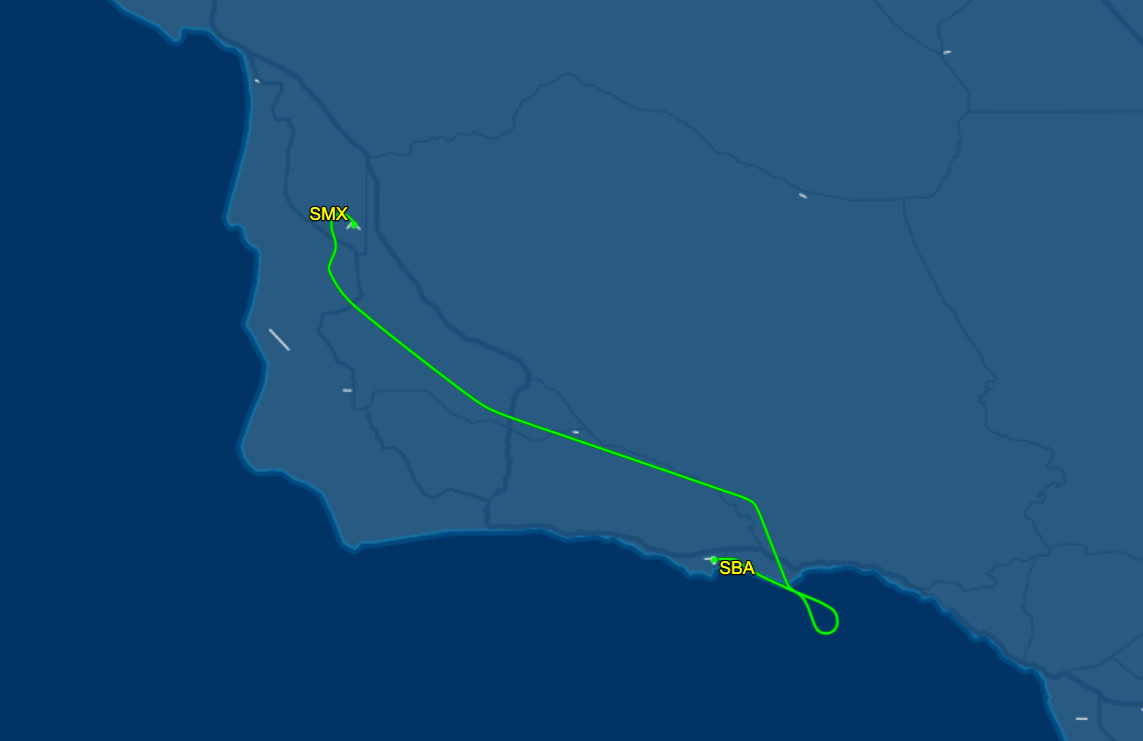

The first image is of the first leg this morning, from Santa Barbara (SBA) to Santa Maria (SMX), just up the coast from Vandenberg Air Force Base. Vandenberg, plus the Dangermond Preserve, is the part of the coastline this flight path avoids. The three-mile-long runway at Vandenberg is the white diagonal strip you see near the coast.

There are reasons for the curlicues of the flight path. Enthusiasts can see the details below.1 But if you follow the animations, you'll get an idea of what even amateur pilots are supposed to juggle and keep up with. This gives me ever greater respect for the pros.

2. Santa Maria to Santa Barbara: ‘Under the hood’ and ‘partial panel.’

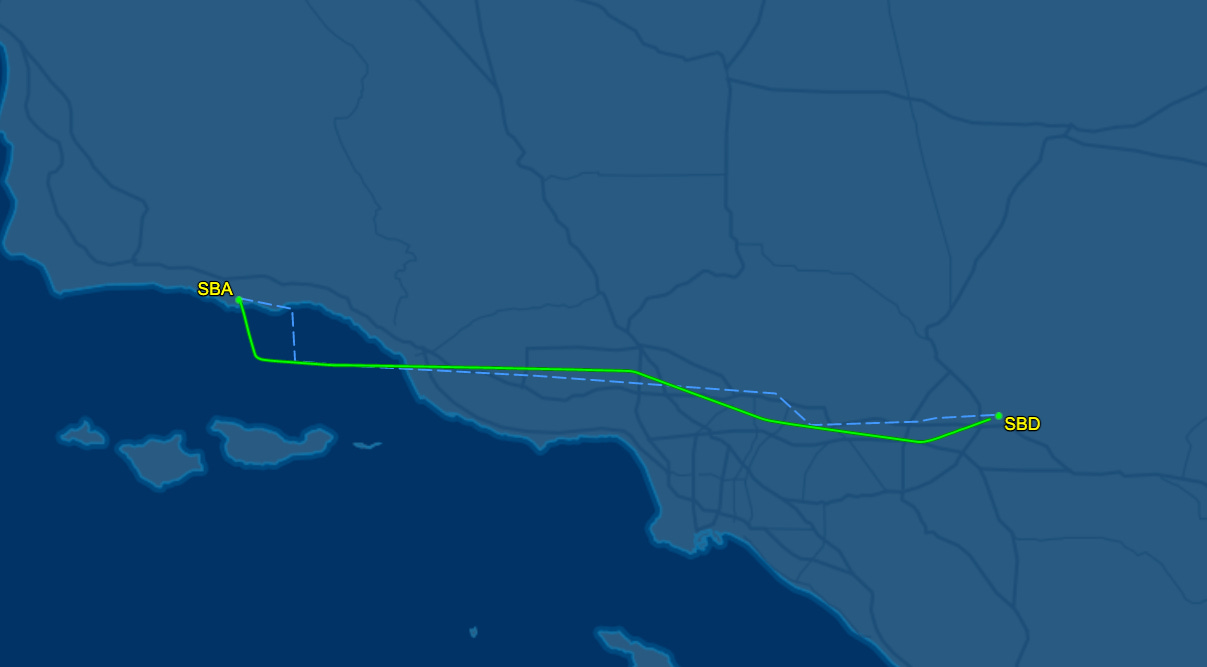

Then it was back to Santa Barbara. This was more demanding on my end, because it was largely “under the hood” (as if the windshield were covered over, and I could see nothing but the instrument panel), and with several of those instruments intentionally disabled. Once more, this is on "what if?” principles.

This route, toward the “VOR or GPS Runway 25” approach at Santa Barbara, involved a course-reversal turn over the ocean, and a rapid descent, to shift from crossing the coast-range mountain ridge to approaching a sea-level airport.

Flying this part under the hood—in clear-sky conditions, with an instructor pilot on the alert in the right seat—made me think of the challenge of self-driving cars. The easier part for cars is that everything is at ground level. The harder part is that pedestrians are popping out ahead of you, and other cars are running stop lights and doing unexpected things. We already have self-landing airliners; it will be a long while until we have fully self-driving cars.

3. Santa Barbara to San Bernardino: Back across the Southland.

The third was a return trip, after the IPC drills, to Deb’s and my current locale near the San Bernardino airport, which as a child I knew as Norton Air Force base. On this leg I benefitted from tail winds, and also from a feature that works great in Southern California but that I haven’t encountered in the same form on the East Coast.

This feature is “Tower Enroute Control” — a kind of automated routing that enormously speeds and simplifies passage through some of the country’s most crowded airspace. (I see from the aviation group AOPA that these exist mostly in California, and parts of Texas and Louisiana, and sort of in parts of the Northeast.) All around me were airliners headed to LAX or Ontario, and smaller jets headed to Burbank and Van Nuys. It was all amazingly smooth. Other congested areas might learn from this system.

At San Bernardino, I got out of the plane. It was freshly repaired after a seemingly endless series of mechanical headaches. I was freshly certified as “instrument proficient.”

For now.

I am sharing the images and animations because I think they’re interesting. I hope others do too. My thanks and admiration to all who make these safe miracles of modern transportation possible. And in particular to Steve Boothby of Above All aviation in Santa Barbara, who was my instructor on these flights.

This is a “LOC DME BC-A” back-course approach at SMX, for which the missed approach leads to a hold. Because this was a “practice approach” under VFR, we were vectored out of the hold to make way for other traffic. We had planned an ILS approach in the other direction, but because of unexpected busyness at a usually quiet airport this just led to a left-downwind approach for a normal visual landing.

Jim, Nice job on the IPC. For those who aren't pilots, I can them that the exercises you went through take a high degree of skill and are mentally and physically draining. I'm sure you slept well, but were justifiably satisfied in completing the Instrument Proficiency Check.

Also, you've done your typically superlative job of making all this understandable to non-pilots. There is so much beauty in what we do - not just in the act of piloting, but in the commitment to lifelong learning, proficiency, focused decision-making and so forth.

I love the quotes from Sully and St. Exupéry. I have his book "Wind, Sand & Stars" on my night table.

So, I thought I'd share my favorite aviation quote. The author is unknown to me, but I love this sentiment:

"The ultimate responsibility of the pilot is to fulfill the dreams of the countless millions of earthbound ancestors who could only stare skyward ...and wish."

Awesome ongoing requirements for private pilots! I was spared such possible rigor, when I scored zero on a depth perception test after two years in the AFROTC. I am thankful that, so far, I’m not required to take an eye test for my driver’s license.