September Song: The 50 Autumns of the Leaf Blower

We've just lived through 50 years of an invention that transformed neighborhood life in much of America, the gas-powered leaf blower. That era is coming to an end.

This photo ran in the Denver Post 49 autumns ago, in 1974. It is of young Ellen McKay, then age 4, raking leaves. The picture has a time-capsule quality, in capturing one of the last leaf-raking seasons before gas-powered blowers transformed the rituals and sounds of this season, and eventually all seasons, in much of the United States. (Ira Gay Sealy/Denver Post via Getty Images)

This note is my regular update1 on a technology that came more or less out of nowhere, spread rapidly across the country with ever-mounting environmental and public-health effects, and now is nearing its end.

The theme for this installment is the elegant Kurt Weill / Maxwell Anderson 1930’s September Song, about time speeding up as things near their end. I invite you to listen to Frank Sinatra’s 1965 rendition as you read what follows. Or Earth, Wind & Fire’s classic from the late 1970s, September. Or the Pomplamoose cover of September. All suit this time of year and this theme.

To every thing there is a season.

The seasons change; the leaves begin to fall.

Fifty years ago, in yards and parks across the United States, the sound of this season would have been the whoosh and scrape of people with their rakes, gathering leaves into piles. Followed by the sounds of children jumping into the piles, which I’m sure is what happened soon after the Denver Post photographer took the picture above, in 1974.

Then, thanks in part to a man named Aldo Vandermolen, over these past fifty years the autumn soundscape dramatically changed. By many accounts Vandermolen, who died six years ago at age 79, invented (or was one of the pioneers in creating) the device whose sound now characterizes this season and so much of the rest of the year.

Aldo Vandermolen was born in pre-WWII Holland, grew up in Brazil, and came to the US as a Princeton undergraduate, where among other things he played varsity soccer. As the Princeton Alumni Weekly reported in a memorial note, after his graduation Vandermolen got a Harvard MBA and spent time at some large corporations. Then (emphasis added):

His life’s work was his family’s business, Vandermolen Corp. in Livingston, N.J., serving as sales manager, then president. There he invented the backpack leaf blower, a portable wood chipper, and an electronic insect killer.

The mid-1970s brought one of the greatest eras in American cinema: Godfather, Star Wars, Jaws, American Graffiti, Saturday Night Fever, and many more. It brought us too many great pop musicians to name. But it also brought stagflation, and urban decay, and ugly cars, and ugly clothes. And the gas-powered leaf blower.

Through all the millennia before the mid-1970s, leaves had fallen and blowerless people had somehow survived. After the mid-1970s, gas blowers became standard equipment for lawn crews, and routine appliances for many suburban households.

A trivial-seeming issue, with enormous consequences.

Why is this worth thinking about, even for a minute? Here is a summary of the many previous posts on this theme, and of the evidence and testimony that persuaded the Washington DC City Council five years ago to vote unanimously in favor of a ban on gas-powered blowers:

Public health and environmental justice. The primitive two-stroke gas engines in these machines, already outlawed for most uses except lawn care, are direct health threats to the people who use them. In big cities this typically means hired crews, whose members are typically low-wage, in many cases recent immigrants, and rarely with long-term health coverage. They are exposed all day to PM 2.5 particulate pollution and carcinogenic emissions. By the time they are in their 30s or 40s, many will have significant, permanent hearing loss and other health problems. (See expert discussion here.)

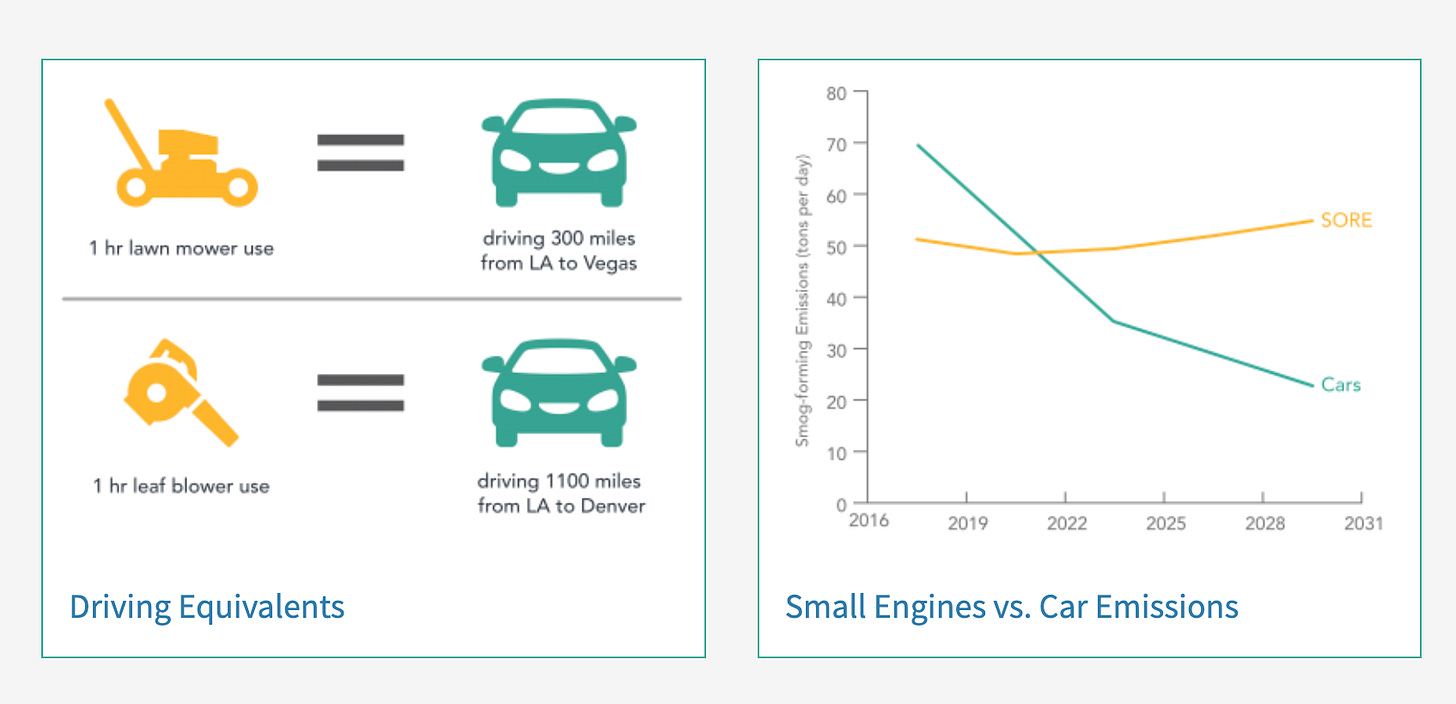

Disproportionate climate and pollution effects. These primitive two-stroke engines, whose technology is more than a century old, are dirtier and more polluting than virtually any other form of machinery still in legal use. Today’s cars and trucks, even the gas-powered ones, put out only 1% as much air pollution as their counterparts from the 1970s.

Two-stroke engines sloppily burn a slurry of oil and gas, and spew the rest out as aerosols and exhaust. The California Air Resources Board has said that two-stroke lawn equipment puts out more ozone and related pollutants than all the millions of cars and trucks in the state combined. As our current president might once have put it, these are a BFD.

California Air Resources Board chart. Habitat destruction. The focused 200-mph wind out of these blowers, an intensity unknown in nature, destroys plant and animal habitat, blasts away topsoil, converts pesticide residue, animal remains, and animal feces to aerosol, and is generally bad. Do you miss the fireflies you used to see in the summer? One of their big enemies is blowers that eradicate the organic shelter in which their eggs and larvae would spend the winter.

Rapid arrival of battery alternatives. The obvious modern alternative is at hand, in the former of battery-powered blowers. All the leading manufacturers are now promoting battery models. A company called EGO has led with a battery-only line. (We have an EGO blower, which works great.) Some landscaping contractors are also welcoming the change.

‘Sound footprint.’ Oh, and by the way, it’s not your imagination: The noise of gas blowers really is different. The unique low-frequency vibrations from gas blowers penetrate walls and windows and give gas blowers a ten-times larger “sound footprint” than battery models.2 To say nothing of the comparison with rakes.

City by city, the bandwagon effect.

That’s the background. Here’s the recent news, summary style.

One major city, Seattle, has mandated a ban on gas-powered blowers. You can read more here, here, here, and here.

The nation’s capital, Washington DC, is nearly two years into a very successful implementation of a forced shift away from gas-powered blowers. Living here, I can tell you: while imperfect it has made an enormous difference. And DC has implemented an effective reporting-and-enforcement system, which can be a model for other communities.

Miami Beach, Florida, has implemented a ban.

So has Pasadena, California.

So has White Plains, New York.

So, recently, has Montclair, New Jersey. A friend there reports, “this was a grassroots, resident-led effort. Our work, not part of a formal group, truly paid off. If anyone would like to learn more, please reach out at glbmtcnj [at] gmail.com."

Similar movements are underway from coast (Oregon) to coast (Virginia and Maryland).

Many cities in California, notably including Los Angeles, ironically banned leaf blowers “too soon” — many years ago, before battery models existed. Now the state as a whole is behind the push toward practical electric alternatives.

No doubt you’ve noticed that the big cities on this list are big cities, and the smaller ones are “suburban.” Does this mean the anti gas-blower push is an elite affectation? Not really, and here’s why:

-First, remember that, as recounted here, the DC measure passed the DC City Council with unanimous backing from all eight Wards of a racially and economically highly diverse city. It’s now part of the District’s ambitious, District-wide “Sustainable DC” initiative.

-Second, the suburbs are where the issue is most acute, because that’s where the lawns are. Before the 1970s, people thought their lawns could be the envy of the neighborhood without mechanized blowing. That time might come again.

-Finally, remember that the people paying the steepest price, through damage to ears and lungs, are not the people in the big houses but the crews they hire to make their lawns look “perfect” and unnaturally leaf-free. And apart from the lawn crews, children, the house-bound, older people, and those with chronic diseases are also most affected by pollution from gas blowers.

Dinosaurs ruled the Earth for more than 100 million years. These modern dinosaurs will have a much shorter run.

Somewhat related: next up in this space will be a discussion of politicians as they age.

As a technical point, discussed in the studies presented to the DC City Council: high-frequency noise, like a dental drill or a kitchen blender, can be very annoying — but it doesn’t “travel.” It falls off quickly with distance, and a wall or even a window will block it. If you’re in the next room, separated by a wall or a closed door, you might not even hear it. But low-frequency noise, like the deep-bass boom-box of a car driving down the street, carries much farther and penetrates walls and windows. Gas blowers produce powerful, penetrating low-frequency noise. Battery blowers produce much higher-frequency noise, with a much smaller “footprint.”

My job is to enforce a gas leaf blower ban in the city I work for here in CA. The information you've shared has been invaluable to me in learning more about the issue and being able to explain why it's necessary. We're having a summit in 2 weeks with other cities in our area to discuss "best practices" in getting people to switch to electric leaf blowers such as bans, enforcement, or incentives.

I'm enjoying a lovely cool morning reading this outside my favorite Portland, OR coffee shop. And of course, as I'm finishing up and reading the footnotes, a man across the street is finally successful at starting his two-stroke blower, and it's time to flee. We can't be rid of these things soon enough