On Knowing When to Go.

Dianne Feinstein staying on creates a problem for her party. Joe Biden staying on solves problems for them.

Dianne Feinstein celebrating her victory in the San Francisco mayoral election in 1979. She had assumed the duties of mayor in 1978, after the gun assassination of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. (Gary Fong photo / SF Chronicle.)

This post is about two older Democratic politicians and their stay-or-go decisions about public life.

It boils down to this:

—Sometimes what helps an individual hurts a larger cause. Things have come to that point for Senator Dianne Feinstein.

—Sometimes it works the other way, and an individual’s interests are aligned with a cause. I believe that applies to Joe Biden’s announcement that he is running for a second term.

Feinstein staying on, at age 89, increases problems for her party. Biden staying on, at age 80, reduces them. Here’s why.

The problem of ‘being in the way.’

In public life as at a social gathering, it’s better to leave too early than too late.

You can think of exceptions. Franklin D. Roosevelt was at death’s door when he ran for re-election in 1944. But in that final stage of the war, it was better for the Allied cause that he stayed.1 The sporting world lost its chance to marvel at Sandy Koufax and Bjorn Borg too soon—but has watched too many other athletes hold on through sad declines. Roger Federer stepped away, because of injury, at a point when our mental images are still of his grace. We are fortunate that Joan Baez and Paul McCartney are performing into their 80s, that Bonnie Raitt is sweeping the Grammys in her 70s, that Robert Caro is at work on his LBJ saga as he nears age 90.

The key difference between most of the people listed above, and these two senior Democratic leaders, is being in someone else’s way. Joan Baez can keep singing, and that doesn’t hurt Billie Eilish. The next novel by Joyce Carol Oates, in her 80s, will not stop writers in their 20s or 30s from making their mark.

But political figures like Joe Biden and Dianne Feinstein are unavoidably in other people’s way. (The same applies in extreme form, on the unaccountable, life-tenure Supreme Court, subject of an upcoming post.) So their decisions about staying or going have big ripple effects.

1) Dianne Feinstein.

From the 1970s onward Dianne Feinstein has been an inspiring and pioneering political figure.

She was in California state government in her early 30s. She became mayor of San Francisco in her mid 40s, after the gun assassination of incumbent Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. She became a U.S. Senator a decade later and has represented the most populous state ever since.2 She has led in countless fields, including campaign finance, gun safety, accountability for CIA torture and cover-up in the Guantanamo era, and more.

But unless she can return to Washington and resume in-person Senate duties immediately, she should make room for someone else.

This is not mainly about whether she is “up to the job” in a subjective sense, though there is reason for concern on that front. Back in 2020 Jane Mayer of The New Yorker wrote a long article about some of Dianne Feinstein's lapses in public and private interactions. The most notable was a televised hearing where she asked a witness a question—and after his answer, asked exactly the same question, seemingly unaware of what had happened.3 Other newspapers have carried similar reports.

But even if the worst were true, she would be far from the only member of the Senate to have stayed far too long. Strom Thurmond, in office well into senescence at age 100, is the most famous of many examples.

In reality, a lot of a legislator’s work can be left to staff—as Thurmond did and Feinstein has done. The real issue in her case is the trench-warfare nature of today’s Senate, which makes her simple physical absence from the Capitol an ever-growing problem. When she’s not in DC, she can’t cast a Senate vote. And that puts all of her Democratic colleagues in a bind.

—Because she’s not present to vote on the floor, the Democrats’ tiny 51-49 Senate margin is that much smaller. Recall how hard Democrats in Georgia and elsewhere fought for Raphael Warnock’s re-election in last year’s runoff, to move beyond a 50-50 standoff? Dianne Feinstein is giving a seat away. Remember when every Senate decision came down to Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema? Dianne Feinstein’s missing vote takes us back toward those times.

—Because she’s not present to vote in committee, the Democrats’ 11-10 margin on the Judiciary Committee turns into a 10-10 tie. The Republicans have used this to stonewall nominations and other actions. Given GOP control of the House, judicial confirmations are the main Democratic ambition through the rest of this term. Feinstein’s absence thwarts them.

She’s also impeding efforts to do something about an overweening and unaccountable Supreme Court. Last month Democrats on the Judiciary Committee considered a subpoena for Chief Justice John Roberts to testify about Clarence Thomas. They couldn’t, because Feinstein’s absence left them at a 10-10 vote. “We don’t have a majority,” the committee’s chairman, Dick Durbin, bluntly said.

Is it sexist to say this about Feinstein and not John Fetterman, the freshman senator who was absent for six weeks while hospitalized for depression? Mainly because of Feinstein’s committee assignments and seniority, her absence has mattered more.

What about Chuck Grassley, a few months younger than Feinstein and also 89? (If you’re wondering, Bernie Sanders is eight years younger than them both.) Or Mitch McConnell, also absent for five weeks in rehab from a fall? If either Grassley or McConnell were hurting the Republicans’ prospects as much as Feinstein is hurting the Democrats’, you’d be hearing the same things from their side.

‘Burning the Days.’

That’s the title of an elegant memoir by James Salter. It’s how I think of Feinstein’s time in the Senate now. Pages are flying off the calendar. She is burning the days.

If you’ve watched legislative cycles, you know there is not that much time for actual “work.” Another election is always just around the corner. There are long recesses and vacations. In the Senate everything is bogged down by filibuster and “holds” and other stalls. A day wasted is gone forever.

There is exactly one way in which Feinstein’s resignation a year-and-a-half early would increase problems for the Democrats. She has already said she will not run again in 2024, and governor Gavin Newsom would need to choose her replacement. That would create a whole new spectacle and source of division for Democrats. My longshot suggestion: name Jerry Brown, the FDR of California politics, on the agreement that he is there only for the remainder of Feinstein’s term. Brown is now age 85. It won’t happen, but it’s fun to think about.4

The choice of how Dianne Feinstein will be remembered is still in her hands. Will the end of her career be paired with Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s, to illustrate the perils of holding on too long? Or will it be used as a contrasting example?5

If she can be in the Capitol, at her desk, and casting votes by next week, she can hold off these questions. Otherwise she owes it to 40 million Californians, 50 other members of the Senate Democratic caucus, and millions who share her goals to step aside, now. She owes it to her own reputation as well.

2) Joe Biden.

We adults all imagine ourselves as younger than we are.

This must be especially so for Joe Biden. He started out as an exceptionally young politician. He won his Senate seat at age 29. Now he is the oldest person to sit in the Oval Office, by far. When Joe Biden came into the White House, he was older than Ronald Reagan when he left.6

Everyone would prefer if Joe Biden were ten years younger, or maybe twenty. Starting with Biden himself. He’s fit and spry for an 80-year-old. But he is of the age where you start using “spry.”

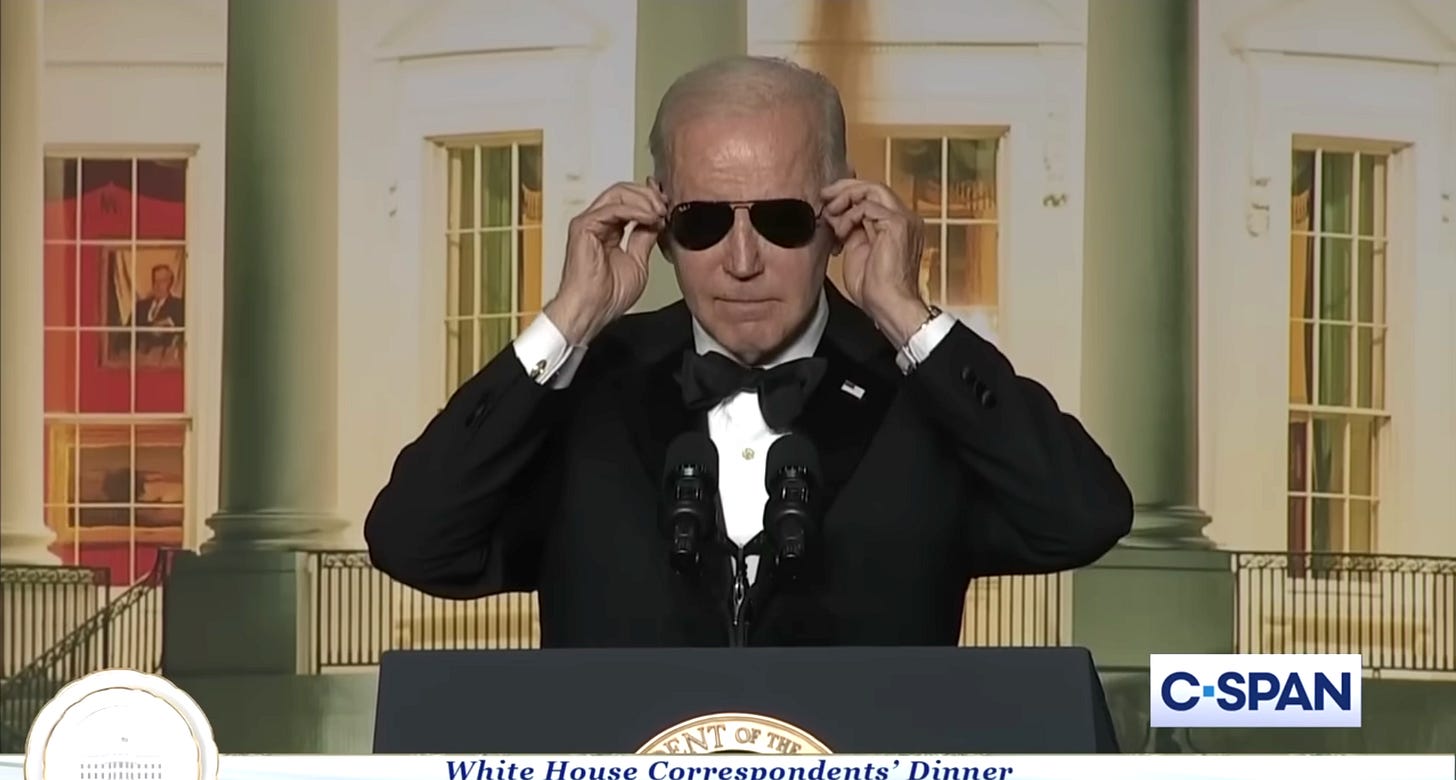

Biden doing his “Dark Brandon” bit at the end of his White House Correspondents Association presentation this past weekend. (Screenshot from C-Span broadcast.)

How can I say that it’s good for Biden to run, given my line on Dianne Feinstein—and in light of consistent polling results showing that even Democrats do not want him to try for a second term?

—On the polling, people may not “want” Biden in the abstract, but he looks better when they start comparing him with alternatives. Over the past year Biden has lagged in general-approval ratings, but polled ahead of specific rivals, like DeSantis or Trump.

—The same is true for the party. Sticking with Biden avoids problems that arise as soon as you think about moving beyond him.

Here’s a summary version of what Biden gives the Democrats:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Breaking the News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.