‘No Man But a Blockhead,’ One Year In

On the writing life—past, present, and future. And why I'm continuing to do it here.

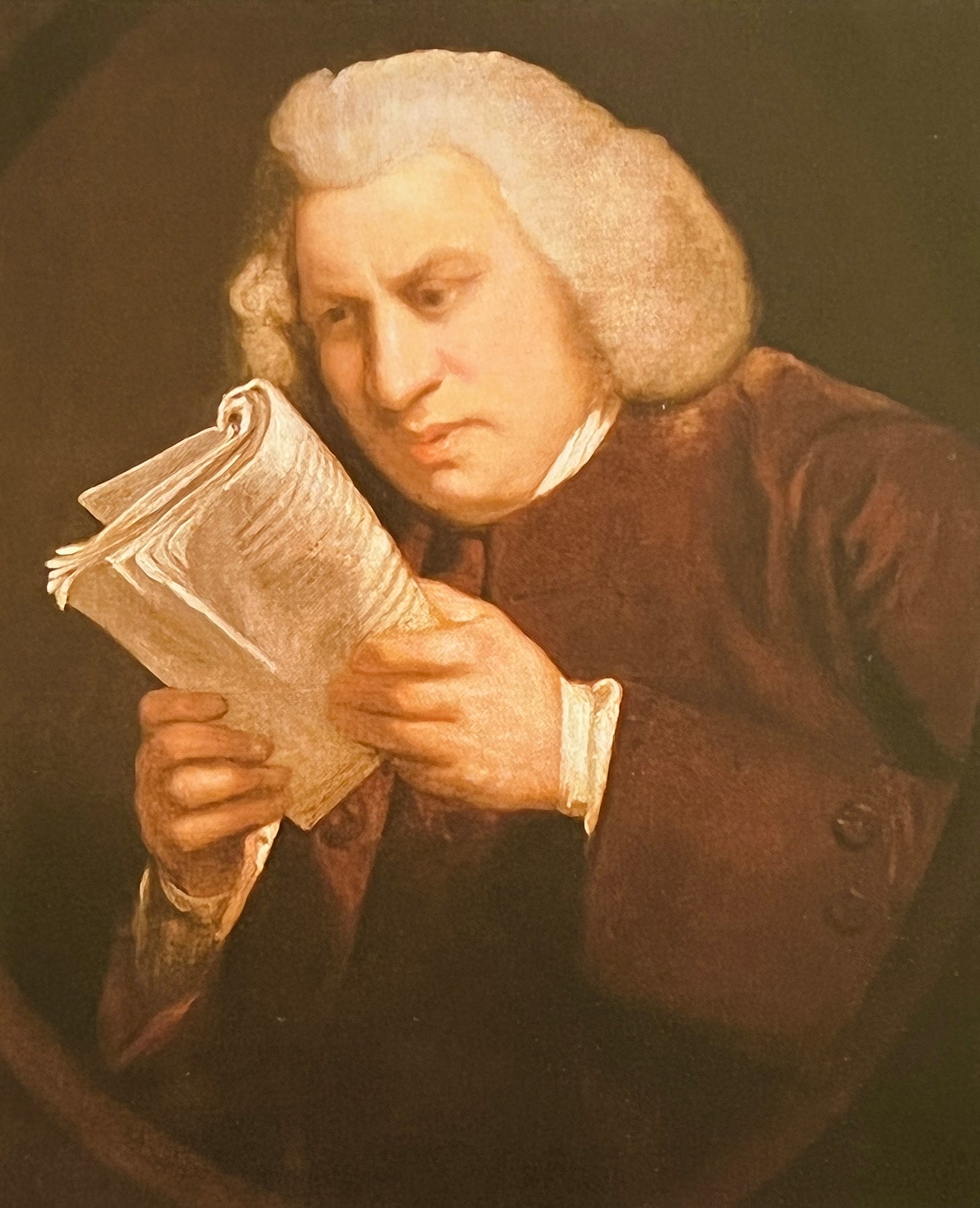

I’ll explain this item’s title and image in a minute. But first, a look back and a look ahead. The purpose of this post is to review what I’ve learned from a year on Substack, and what I plan to do here next.

In early September of last year, I put up the first entry in this site, plus an “about” post explaining what I had in mind.

That was almost one year ago. It was more than 50 years after my first-ever bylined newspaper articles, in the college paper. It was 50 years after I began my first-ever magazine job, in September 1972, at The Washington Monthly, then a startup. I am delighted that my wife, Deb, and I have a new cover story coming up in the September, 2022, issue of that magazine.

Those first Substack “Breaking the News” posts came 25 years after I had published a book, edited by Linda Healey, whose title was also Breaking the News. They came more than 25 years after I’d begun posting online dispatches at my own personal independent web site (with the help of my friend David Rothman), even before these were called “blogs.”

Over all these years I’ve done, apart from a dozen books, thousands of online posts and many hundreds of articles and broadcast commentaries, mainly for The Atlantic but for a range of other places as well.

So this past year has been a continuation, but also a change. It’s a continuation of the work I’ve always done, in a changed venue. I am writing now to express my thanks to the many people who have given their time, attention, and moral and material support to this new undertaking. I also want to explain what it has meant to me, and what I have in mind for my Substack life.

Let’s talk practicalities.

From Samuel Johnson, to David Halberstam

Among the many mentors in journalism I am grateful to, I’ll mention two from those early years whose advice bears on what I am discussing. They were David McCullough, who died this month after a celebrated book-writing career, and David Halberstam, who died as a passenger in a car crash 15 years ago, still in the midst of his own storied career—and on his way to give a talk to young journalism students. The two happened to be near contemporaries of each other, born within a few-month range in the early 1930s. Halberstam was in his early 70s when he died; McCullough, in his late 80s.

They were both in their early 40s when I met them, and I in my mid 20s. They told me about craft, and writing habits, and story telling.

And they also talked about business. Writing was hard, as I already knew, and as they emphasized. The reporting and research is the fun part. But at some point you have to sit down and type. In my experience, what anyone serious about writing likes is having written. The writing life is the best anyone could have. The actual writing part is the challenge.

Writers could never know what next year’s income might be, the two Davids told me. Publishers had more money than writers. So you had to take care to be paid. Find a good agent! Which I am lucky to have done, first with the late Wendy Weil, and in the past decade with our friend Rafe Sagalyn.

Of course both McCullough and Halberstam were reliably best-selling authors, among the most financially secure of anyone in the field. But still they said: choosing to be a writer meant choosing not to have a steady, predictable job or business base.

“This is the life we have chosen!” has been a standard Fallows-household joke when nerves were frayed or money was low. “This is the life you have chosen,” Deb would reply—half-seriously. Obviously it is the life we have chosen, in which she has flourished as a reporter and writer. On this path we together have been fortunate in ways far beyond what we could have expected, and that we try to be aware of every day.

But this early guidance was the context for my often thinking of the famed line from Samuel Johnson, as rendered in Boswell’s Life: “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.”

Of course Samuel Johnson was right—because of the perils of the business and the difficulty of the task.

And of course Samuel Johnson was wrong.

‘No man but a blockhead,’ part two.

Samuel Johnson was wrong because no sane person ever became a writer mainly for the money. Or anyone who did so, did not stay in the business very long before recognizing the mistake.

For some writers, some of the time, this business can be lucrative. Again McCullough and Halberstam in their prime were two examples.

But for most people, most of the time, the writing life is—no joke—a calling. My line about the book business has always been: The only reason to write a book is if you feel you can’t not write it.

The same is true about the reporting and writing business as a whole. People stay in this line of work because they love what is exhilarating and glorious about it — the ability to learn, the license to share and tell — more than they dread what can be sleep-losing, confidence-eroding, and overall maddening about it. The latter boils down to sitting at a keyboard and trying to figure out how to say what you know you mean. I’m not sure whether John Kenneth Galbraith actually said this, but I’ve always credited him with the view that writers strive for the note of spontaneity that comes on the eighth or ninth draft. Someone else told me: the right form of any sentence is already out there in the ether. You just have to exhaust all the wrong possibilities before you find it.

You don’t do this work unless you want to.

Over the decades I have always wanted to do the work of seeing, and learning, and telling, and connecting, and through nearly every minute have enjoyed doing so. And in the past year I have been very fortunate to do so in this space, and am grateful to Substack for making it possible.

In the olden blogging days, a writer could see something, and write out reactions to it, and publish them and get readers’ reactions, all within the span of a few minutes or hours. For understandable reasons, that’s just not feasible at big-time publications any more. They can no longer leave the publishing controls in the hands of individual writers. Among other reasons, the legal exposure and brand consequences are too great.

That’s sensible for publications. But I had gotten used to having those controls in my own hands. As I did, for instance, in this whole series through the 2016 campaign, and in every one of the hundreds of Atlantic posts I filed from China. I have been given the controls again here, and I am grateful for that.

In more than 100 dispatches over the past year, I have been glad to write, and learn, and post: About politics. About China. About technology. About books. About the press. About leaf blowers. About speeches. About airplanes. About family members, from the very young to the young-at-heart. About other topics, all of them available here.

But I’ve had an extra job in this past year, which I’ll explain for what it means about the years ahead.

Building ‘Our Towns’

Here is another chronology:

Nearly ten years ago, on our return from a multi-year residence in China, Deb and I began reporting from parts of America generally left out of mainstream news coverage. That was for an Atlantic series called “American Futures,” with John Tierney, and numerous broadcasts on Marketplace radio, with Kai Ryssdal and his team.

Four years ago, we published a book about this view of America, edited by Dan Frank, called Our Towns.

Three years ago we spent 100 filming days on the road, with the great filmmakers Steve Ascher and Jeanne Jordan, to make a documentary of the same name.

Two years ago, during the lockdown, we worked on production and narration.

Early last year, HBO aired the film, still on HBO Max.

During the same time as working on the film, Deb and I built and launched a new non-profit organization, called the Our Towns Civic Foundation.

Deb and I have spent a lot of the past two-plus pandemic years in what we lovingly call the open-ended “infrastructure week” of starting the foundation. We’ve built a very good website — with the sequential help of designers at Epic Web Studios in Erie, Point Five in New York, Bitwise in Fresno, and Tom Hall and his team in Maine. We’ve had crucial allies — our longtime friends Shelli Stockton and Lincoln Caplan since the very first days, Ben Speggen and Michelle Ellia and too many others to name since then. We’ve received economic backing, at an accelerating pace, most of which is detailed on the site and with more to be announced soon. We are heartened and excited and believe we’re building something that can last.

This will remain a central part of my time, attention, and effort. (I type out these words in a motel in northern Ohio, during a reporting trip to small towns here.) It matters that Americans have a more three-dimensional, less fatalistically “red versus blue” portrayal of our country. It matters that people around the nation who are doing positive and innovative work — about climate resilience, about economic opportunity and inclusion, about new roles for schools and colleges, about reviving “left-behind” cities, about new models for local journalism — know that they are not alone, and can learn from one other. It matters that today’s American story more fully reflect today’s American realities.

I believe in this effort the way people we’ve admired have believed in what they have done. I believe in the way Deb’s parents did, when they sold their small business and went overseas, in their 50s, for the International Executive Service Corps. And in the way my parents believed, when they viewed their small city’s future as their future. And in the way my original magazine employer, Charles Peters and his wife, Beth, believed when they started The Washington Monthly. The way we have seen countless others commit themselves, and make a difference.

As we’ve gained momentum and success we can imagine a time past 24/7 infrastructure week. I can imagine a time when more of my role can be as a writer again.

The year ahead, and the years ahead.

Let’s return to why Samuel Johnson was right. Reporting and writing take work, and they have consequences, so in the long run they need a business base.

Of the 100-plus posts I have done here in the past year, virtually all have been “open”— available to all, paying subscriber or not. The only paywall has been limiting comments on posts to paying subscribers. This open approach is one I wanted to take, because I wanted to get my own feel for this venue, and because I was aware of the awkwardness of asking people to put up money before there was much to read.

Because it’s relevant in discussions of Substack, I should disclose that when the company was offering large and well-publicized guarantees to many writers last year, it made a very generous offer to me. I was grateful to Substack, on this point and many others. But I declined, because I didn’t want to be under that additional pressure.

Instead I’m here on a “pay your own way” basis. Of what subscribers pay here, 10% goes to Substack, and the rest, after various fees, goes to me. That constitutes essentially all of my writing income. Again because it’s relevant I’ll say that of the money Deb and I have raised for Our Towns, all has gone to contributors and staffers, not to us.

Those of you who have paid to offer support in this past year have done so voluntarily. I can hardly express how grateful I am.

I am also grateful to all who, with or without payment, have given their attention here. I recognize that people have many obligations and limited resources.

But in this new year of operations, I will make this a more normal “business” undertaking on my side. I’ll post on a more predictable, regular schedule, which I’ll let readers know about. I’ll work with this rough division of labor: On American-renewal topics, my colleagues and I will mainly post on Our Towns. On everything else, from China to political journalism to the military and all of the above, I will be here. And naturally there will be significant fertile overlap.

Most of what appears here will still be “open.” Anyone interested can still subscribe for free. But I will be introducing a sequence of paid-subscriber features. They will be on a plus/and basis — new features, for which I’ll ask new support — rather than a minus basis, of taking things away. Most of them will involve aspects of community and connection: ways to share experiences, insights, mutual support, being “backstage.” Because I prefer to show you something, once it’s developed, than tell you about something before it’s ready, I’ll wait to unveil what I have in mind.

But I believe that asking for support is a sign of taking this enterprise even more seriously. Writing is a privilege and is also work. No man but a blockhead…

My thanks; stay tuned; and note the button, below.

I've been reading your work since my freshman year in college. You and Ben Beach and John Powers. I look forward to the next 50 years of your writing.

Your posts have been wonderful, and I look forward to many more.