Learning from Disasters: Political Media Edition

We expect course-corrections from other institutions. Here are a few ways we in the media could learn from our mistakes.

We all make mistakes. People, organizations, countries. The best we can do is admit and face them. And hope that by learning from where we erred, we’ll avoid greater damage in the future.

Relentless and systematic self-critical learning is why commercial air travel has become so safe. (As described here, and recent posts about the JFK close call here and here.) Good military organizations conduct “lessons learned” exercises after victories or defeats. Good businesses and public agencies do the same after they succeed or fail.

We in the press are notably bad at formally examining our own errors. That is why “public editor” positions have been so important, and why it was such a step backward for the New York Times to abolish that role nearly six years ago. Similarly this is why I think the generally excellent ProPublica is making a mistake in flatly refusing to address questions about its notorious “lab leak” story from last fall.

Three welcome words: ‘I Was Wrong.’

Here’s another example of facing a mistake, versus trying to ignore it: the buildup to the “Red Wave” that never happened in the 2022 midterms.

Pundits and much of the mainstream press spent most of 2022 describing Joe Biden’s unpopularity and the Democrats’ impending midterm wipeout. As it happened, Biden and the party nationwide did remarkably well.

On the morning after the election, conservative pundit Henry Olsen had an opinion column in the Washington Post headlined “I Was Wrong About the Midterms. Here’s What I Missed.”

That’s to his credit. (For the record, I disagree with him about most things.) A number of other writers quickly owned up to misjudgment.

By comparison: In its news coverage, not the opinion page, the New York Times had been among the most certain-sounding in preordaining the Democrats’ loss. This was its front page just one day before the election:

One lead story had the sub-head “Party’s Outlook Bleak,” referring to Biden and the Democrats. It mentioned forecasts of “a devastating defeat” in the midterms. The other story’s sub-head was “G.O.P Shows Optimism as Democrats Brace for Losses.” The first paragraph of that story said voters “showed clear signs of preparing to reject Democratic control.” Again, these were news, not opinion, pieces.

Seven weeks later, the Times ran a front-page story on why so many people had called the election wrong—and how the Red Wave assumption, fed by GOP pollsters, hampered Democrats’ fund-raising in many close races. The only mention of the paper’s own months-long role in fostering this impression was a three-word aside, in the 13th paragraph of a thousand-word story. According to the story, the GOP-promoted Red Wave narrative …

…spilled over into coverage by mainstream news organizations, including The Times, that amplified the alarms being sounded about potential Democratic doom.

The three words, in case you missed them, were “including The Times.”

An NYT public editor like Margaret Sullivan or Daniel Okrent might have gone back to ask the reporters and editors what they should learn.1 And how one party's strategy could have "spilled over" to shape a major paper's coverage.

Henry Olsen’s three words were better. “I was wrong.”

Lessons for readers, and reporters.

What are lessons-unlearned signs that readers can look for, and that we reporters and editors should avoid?

An easy one is to spend less time, space, and effort on prediction of any sort, and more on explaining what is going on and why.

Here are a few more:

1. Not everything is a ‘partisan fight.’

Consider yesterday’s front page of the New York Times—which I mention because the paper has such influence on the rest of the media.

—On the one hand, this page illustrates what is (mostly) magnificent in the Times’s coverage. That’s the “map is worth a million words” depiction of how much California’s recent epic rainfall has, and has not, relieved its long-term drought. The digital-graphics and mapping teams at the Times should get their own Pulitzer every single year.

—On the other, it illustrates the drawbacks of reflexively casting issues as political struggles, by describing a potential debt-ceiling crisis as a “partisan fight.”

In case you have forgotten, the “debt ceiling” is a serious problem but not a serious issue. In brief:

-The debt-ceiling is a problem, because failing to take the routine step of raising it has the potential to disrupt economies all around the world, starting with the U.S.

-It is not an issue, because there are zero legitimate arguments for what the GOP fringe is threatening now. (See Thomas Geoghegan’s recent article. Also I did a six-part series on the topic back in 2021. The issues are the same, and the links are below.2) It’s like threatening to blow up refineries, if you don’t like an administration’s energy policy, or threatening to put anthrax into the water supply, if you don’t like their approach to public health. These moves would give you "leverage," just like a threat not to raise the debt ceiling. But they're thuggery rather than policy.

If you prefer a less violent analogy: since these payments are for spending and tax cuts that have already been enacted, this is like refusing to pay the restaurant check after you’ve finished dinner.

This is not a “partisan fight” or a “standoff.” Those terms might apply to differences on immigration policy or a nomination. This is a know-nothing threat to public welfare, by an extremist faction that has put one party in its thrall.

Reporters: don’t say “standoff” or “disagreement,” or present this as just another chapter of “Washington dysfunction.”

Readers: be wary when you see reporters using those terms.

2. Not everything is a ‘perceptions’ narrative.

Here are some more phrases that should make you wary as a reader. They are phrases like “a picture emerges” or “paints a picture.” These are clichés a reporter uses to state a conclusion while pretending not to do so. Others in the same category: “sure to raise questions”; “suggest a narrative”; “will be used by opponents”; and so on.

Consider again from the NYT, this new “inside” report on Joe Biden’s handling of classified documents.

It was a classic legal strategy by Mr. Biden and his top aides — cooperate fully with investigators in the hopes of giving them no reason to suspect ill intent. But it laid bare a common challenge for people working in the West Wing: The advice offered by a president’s lawyers often does not make for the best public relations strategy.

This might be a “classic legal strategy.” It might also be following the rules. The presentation reflects a choice about how to “frame” a story.

The mainstream press makes things an “issue,” by saying they are an issue. Or saying “raises questions” “suggests a narrative,” “left open to criticism,” “eroded their capacity,” and so on. This gives them the pose of being “objective”—we’re just reporters, But it is a choice.

My long-time friend Jonathan Alter, author of an excellent book on Jimmy Carter, has an op-ed column in the NYT today arguing that the narrative about Biden’s handling of the few classified documents will be hugely destructive to him and the Democrats. Even though, as he says, the realities of his classified-documents case are in no way comparable to Donald Trump’s. (More on the differences here.)

As a matter of prognostication, maybe Jon Alter is right. I hope he isn’t. As he notes, Biden in office has time and again beaten pundit expectations.

But as a matter of journalistic practice, I think our colleagues need to recognize our enormous responsibility and “agency” about what becomes an issue or controversy. “Raises questions,” “suggests a narrative,” “creates obstacles”—these aren’t like tornados or wildfires, things that occur on their own and we just report on. They are judgments reporters and editors make, “frames” they choose to present. And can choose not to.

Which leads us to…

3. Not all scandals are created equal.

Here are things enormously hyped at the time, that look like misplaced investigative zeal in retrospect:

— (a) The Whitewater “scandal.” For chapter and verse on why this was so crazy, see the late Eric Boehlert, with a very fine-grained analysis back in 2007; plus Eric Alterman at the same time; plus Gene Lyons, who lives in Arkansas and wrote a book called Fools for Scandal a decade earlier.

I would be amazed if more than 1% of today’s Americans could explain what this “scandal” was about. I barely can myself. But as these authors point out, it led domino-style to a zealot special prosecutor (Kenneth Starr, himself later disgraced), and to Paula Jones, and to Monica Lewinsky, and to impeachment. It tied up governance for years.

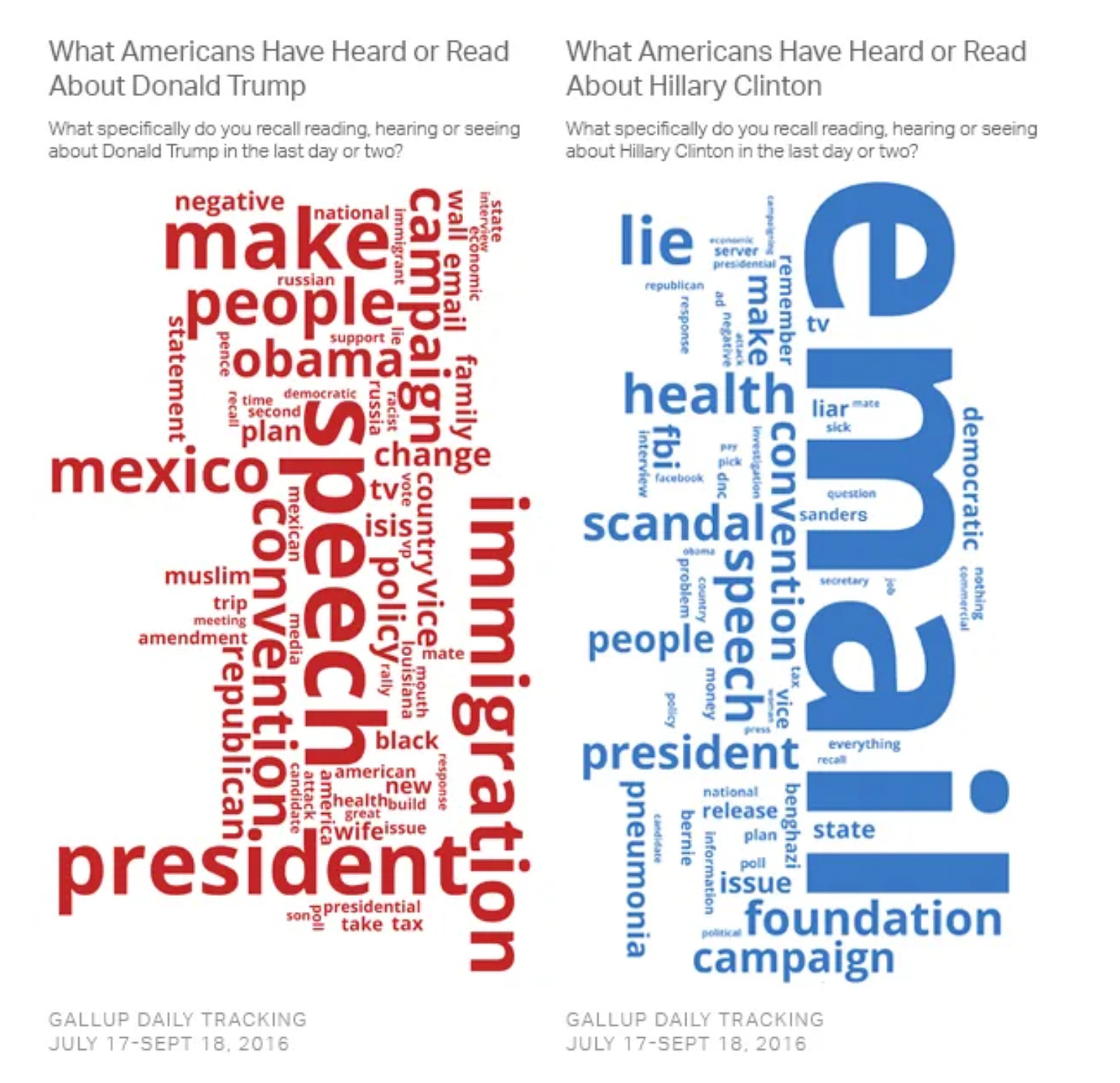

—(b) The but-her-emails “scandal” involving Hillary Clinton in 2016. A famous Gallup study showed that the voting public heard more about this than anything else.

Will any historian ever say that the Whitewater land deal was reasonable grounds for paralyzing the government? Or that “her emails” were reasonable grounds for bringing Donald Trump to the White House? Can people today explain what the Hillary Clinton email “scandal” actually involved?

I doubt it. Yet it was what our media leaders emphasized. I’m not aware that any of them has publicly reckoned with what they should have learned from their choices in those days.

But today’s news gives us a chance to learn, with:

—(c) The Biden classified-documents “scandal.”

What unites these three “scandals” is that there was something there. Possibly the young Bill and Hillary Clinton had something tricky in their home-state real estate deal. Probably Hillary Clinton did something with her emails that she shouldn’t have. Apparently Joe Biden should have been more careful about the thousands of documents that must be in his offices, libraries, etc.

But “something” does not mean “history-changing discovery.” In the 50 years since the original Watergate, the political press has palpably yearned for another “big one.” So every “scandal” or “contradiction” gets this could be the big one treatment. And this in turn flattens coverage of all “scandals” as equivalent. It’s a slurry of “they all do it,” “it’s always a mess,” “they’re all lying about everything” that makes it hard to tell big issues from little ones.

We see this with bracketing of the Trump and Biden “classified document” cases. They both have special prosecutors, So they can be presented as a pair.

Human intelligence involves the ability to see patterns. (Two cases involving classified documents!) But also the ability to see differences. (In one case, a president “played politics” by cooperating with the authorities. In another, by lying to and defying them.)

The similarities are superficial. The differences are profound.

From past errors of judgment, we in the media can learn which to emphasize.

Okrent and Sullivan were two of the notable Public Editors at the NYT. In a memo announcing the end of that position in 2017, the Times’s publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, said that “our followers on social media and our readers across the Internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be… Our responsibility is to empower all of those watchdogs, and to listen to them.”

See installments from 2021: on September 24, September 26, September 28, September 30, October 5, and October 7.

The elephant in the room (which you did not address) is which way these "mistakes" tilt. The error is almost never in favor of democrats - a fact our beloved Eric Boehlert never failed to shout out.

Thank you so much for your article that clarifies why I feel so outraged when reading a story with excessive "both sidesisms." I mentally shake my fist at reporters/editors who blow some things out of proportion or try to say two wrongs are equally bad when it just isn't so. I've heard that outrage draws readers in and holds their attention, but I could tune into Faux News if I wanted outrage every day. Most days I just want accurate information.