It's Raining Airplanes. Three Saves in Two Weeks.

Aviation has always been risky. Here's an innovation that makes it safer.

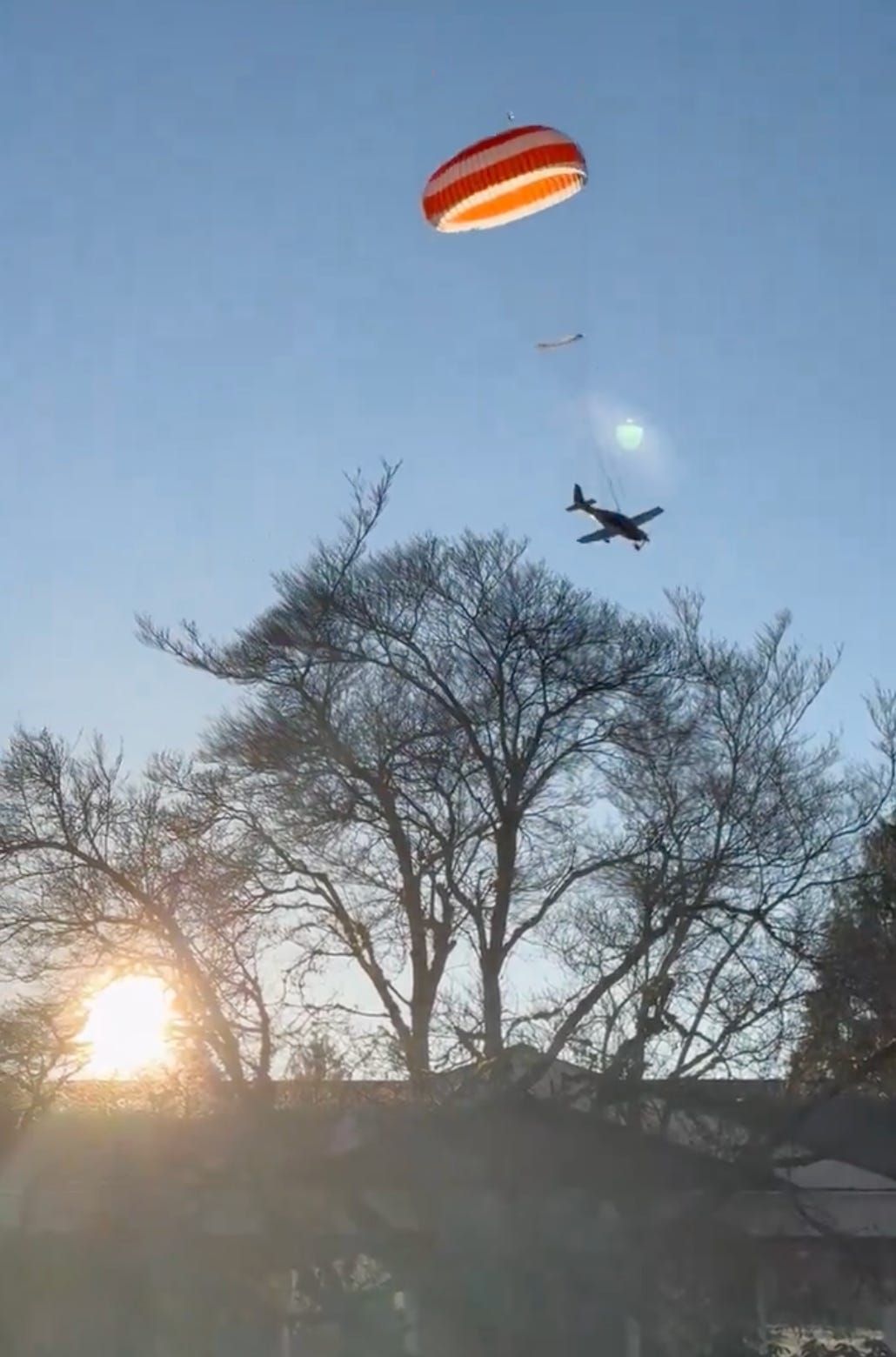

After their plane’s engine failed, over remote terrain in far northern California early this month, a young family of three descended under the plane’s parachute to a safe landing. (Photo by Kristina Carrara, via Shelter Cove Fire Department.)

In just the past two weeks, pilots and their passengers have escaped unharmed after three separate incidents across the country that could have had much more tragic outcomes. They were in greater Seattle, on the remote northern coastline of California (shown above), and in southern Georgia. This post is a review of their similarities, and how those aboard were saved.

First, a word about how we got here. Twenty-five years ago I made a reporting trip to Duluth, Minnesota, on a project for the New York Times Magazine. I was writing a story about a startup company with a revolutionary goal: to build airplanes with a built-in parachute for the entire plane.

The two young brothers who founded the Cirrus Design company, Alan and Dale Klapmeier, designed the plane to avert some of aviation’s many nightmare scenarios, As Alan Klapmeier often put it, “the penalty for a mistake or bad luck should not be death.” This idea has made Cirrus far and away the most popular small airplane in its class around the world.1

Well over 10,000 Cirrus aircraft, the vast majority of them single-engine propeller planes but also counting more than 500 parachute-equipped small jets, are in action around the world. Now, let’s look at three planes recently removed from the active-duty rolls. The “N-numbers” are the registration numbers on each plane’s tail.

March 5: Bellevue, Washington, N927CS.

Screenshot of video from Bellevue police department showing the Cirrus floating down. That’s obviously the setting sun in the lower left. The white circle just above the airplane is from a reflection in the camera’s lens.

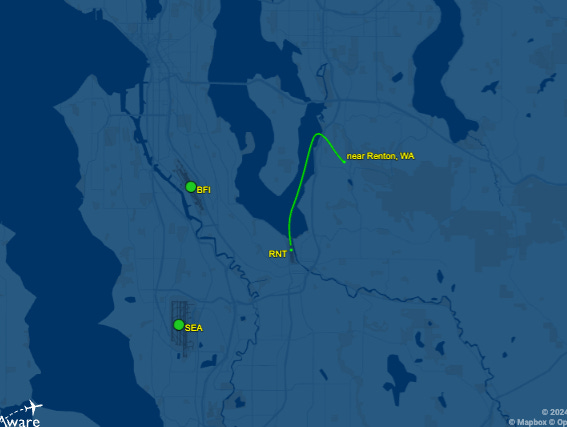

Two weeks ago today, late on a Tuesday afternoon, a pilot and his flight instructor took off from Renton airport, on the southern end of Lake Washington outside Seattle. They were flying a Cirrus SR22T, a different version of the plane Deb and I have flown for many years.

Not long into the flight, for reasons still unknown, the plane’s engine failed. If you click the audio below you can hear the pilots’ terse discussion with the controller at Renton field. The first message (about ten seconds in): Engine failure! The second: We’re not going to make it back to the runway, after the Renton controller has cleared them for an emergency landing. Then, third, about 20 seconds before the end of this clip: “We’ve pulled CAPS.” That is the acronym for the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System. The message means that they’re now drifting down.

Below them, as the plane headed down, the pilots saw only trouble. Local airports were all beyond their gliding range—Renton, Sea-Tac, Boeing Field. Within range was either water or dense residential and industrial areas. And ahead of them were the packed lanes of I-90.

You can get a fascinating simulated view of their perspective in this YouTube video created by Mark Waddell, head of aviation-safety efforts for the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association, COPA. (Rick Beach, of COPA, has been a leading international evangelist for parachute use. Cirrus’s training program for the parachute is available online here.) The video, using software called FlySto, matches tracking info about the plane’s speed, altitude, and heading with computer images of the region. About thirty seconds into this video, you’ll see the plane begin to plummet as the engine fails. The graph below the simulation shows the plane’s altitude.

Once they deployed the parachute, the pilots had no control over the plane’s descent rate and only limited control over its direction. But their efforts, and the wind, and chance, brought them down into a wooded area—rather than into houses or onto a freeway. Those familiar with the Seattle area will recognize the plane’s path as shown on FlightAware, from Renton until it ended up in Bellevue just east of Mercer Island:

Here’s a video of how the plane looked when it was descending, ending with photos of how it looked after it came down. The people were out of the plane at this point.

(Screenshot from Bellevue Police Department video.)

Both pilots aboard the plane walked away. The plane itself was damaged as it drifted at parachute-descent speed through branches and onto a hill. Without a parachute, the plane would have slammed at 75 mph or faster into whatever it hit.

For more local coverage of the story see the Seattle Times, KOMO, KING, and KIRO here and here.

2) March 8: Shelter Cove, California, N2824M.

Three days later, at around 1 pm on a Friday afternoon, a young family of three took off in their Cirrus SR22 from the beautiful-and-remote Shelter Cove airport, on the far northern coast of California in Humboldt county.

Shelter Cove is renowned as a spectacular fly-in destination, delightful when everything goes right. What can go wrong is frequent low coastal fog, blanketing the runway that is right alongside the ocean. And if something does go wrong on the way into or away from the airport, the surroundings are much less forgiving than those around Puget Sound. To the west, the frigid Pacific, distant from any rescuers’ boats or aircraft. Immediately to the east, near vertical escarpments that are part of the neighboring King Range.

But the family at Shelter Cover—a husband and wife in their late 30s, with their 2-year-old child in the back seat—took off and almost immediately ran into engine problems. Usually when a plane takes off, it just keeps going. In my Cirrus years since 2000, I’ve never had an engine or electrical-system problem during those crucial first two or three minutes as you get safely away from the ground. But this plane got only to about 2700 feet before it lost power, for whatever reason.

Below is a screenshot from another FlySto recreation, from Mark Waddell, showing the course of their flight. The path in blue, on the left, is their initial ascent. The white bar shows the moment of engine problems, when the plane stopped going up and started going down. The remaining, mustard-colored path shows where they began dead-sticking down, and then pulling the parachute. You can see the chilling FlySto simulation of the in-cockpit view here.

Like the plane in Seattle three days earlier, this one landed in trees and brush. As the plane fell through the tree cover the cabin was flipped upside down and ended up looking like what you see below. (For orientation, that’s one of the wheels pointing upward, and the nose of the plane is at the bottom left. The horizontal white panel on the upper right side of the image appears to be the plane’s horizontal stabilizer, which must have been snapped off on impact.)

(Photo via Shelter Cove Fire Department on Instagram.)

The young family aboard was fine. Without the parachute, or the robust shock-absorbing construction of the airplane’s fuselage, they would not have been.

More excellent coverage from Kym Kemp in the local Redheaded Blackbelt, plus Mendofever, Fox, and even the NY Post. All make the parachute the hero of the story.

3) March 16: near Reidsville, Georgia, N469GB.

Three days ago, on Saturday afternoon, a couple and their dog took off from Brunswick, Georgia, in a Cirrus SR22. About 30 minutes into their flight the engine failed for some reason. As their plane headed toward the ground they looked around for places to land; realized they were beyond gliding range of the nearest airport, in Reidsville, Georgia; and deployed the parachute.

This is how their plane looked on the ground, with a local rescue crew examining it.

All aboard were fine, including the dog.

What have we learned here? Apart from the reminder that pursuing aviation is unforgiving and always presents risks?

We may have learned something about engines. Three major emergencies, in two weeks? Even in a fleet of many thousands of airplanes, that commands attention. Certainly it has mine. Maybe it’s pure coincidence; maybe it involved something pilots did or didn’t do; maybe it’s something else. More on this, as more is known

And we’ve been reminded, via the parachutes, of the nature of progress, even in this niche field. The innovators who bucked conventional wisdom and plowed their way through regulatory obstacles to create “the plane with a parachute” believed they would save lives. So far this month they’ve saved at least seven. Plus the dog!

And speaking of averting disasters, we’ll get back to national politics shortly.

From the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association home page. The entire Cirrus fleet now numbers more than 10,000 piston- and jet-powered aircraft, all with parachutes.

For reference: I’ve told the story of Cirrus many times over the years. These include in the original NYT Magazine story; in a subsequent book; in an Atlantic cover story; and in numerous web posts, including in 2013, in 2015, in 2016, and in 2022. Last year I wrote in The Wire China about the Cirrus company’s fate as a wholly owned subsidiary of the Chinese state aviation ministry. As I’ve noted many times, my wife Deb and I bought one of the earliest Cirrus SR20s when it first came onto the market in 2000, and we flew our SR22 around the country for the travels that went into Our Towns.

There's something going on here engine-wise. Those three failures are two more than I knew of in ten years of flying around the Central Valley from Sac Exec. And the third wasn't an engine failure so much as it was some idiot who put the baffles in backwards on my Grumman Tiger's engine, a fact I discovered taking out of Fresno headed for VNY, but by the time I was at 3,000 feet the cylinder head temps were at the top of the yellow headed for red. I throttled back and saw Porterville airport off to the right. Fortunately my flight instructor had taught me to fly the Tiger with the throttle chopped from the point of entry to downwind, all the way to touchdown, so I was very familiar with turning it into a glider. Set up best descent and arrived over Porterville at 1800', spiraled down to pattern altitude and then put it on the ground. The mechanic just shook his head when he looked in the engine compartment.

But three failures over such a short period, there's something more than an idiot misplacing the baffles.

Yes, I'd say it's time for Cirrus to take a magnifying glass to these engine problems. Saving lives is the number one priority, of course, but there is also the matter of the outrageously expensive vehicle that may or may not be reusable.

I once talked with a colleague who was a former military pilot; I said I had heard that a good landing is one you can walk away from. He said, "Yes, and a great landing is one where you can still use the airplane."