Election Countdown, 59 Days to Go: Nippon Steel vs. the Electoral College.

Why is Joe Biden preparing to block the sale of US Steel? For 19 reasons: Pennsylvania's 19 electoral votes. That logic may be irrefutable in an election year. But it has real costs.

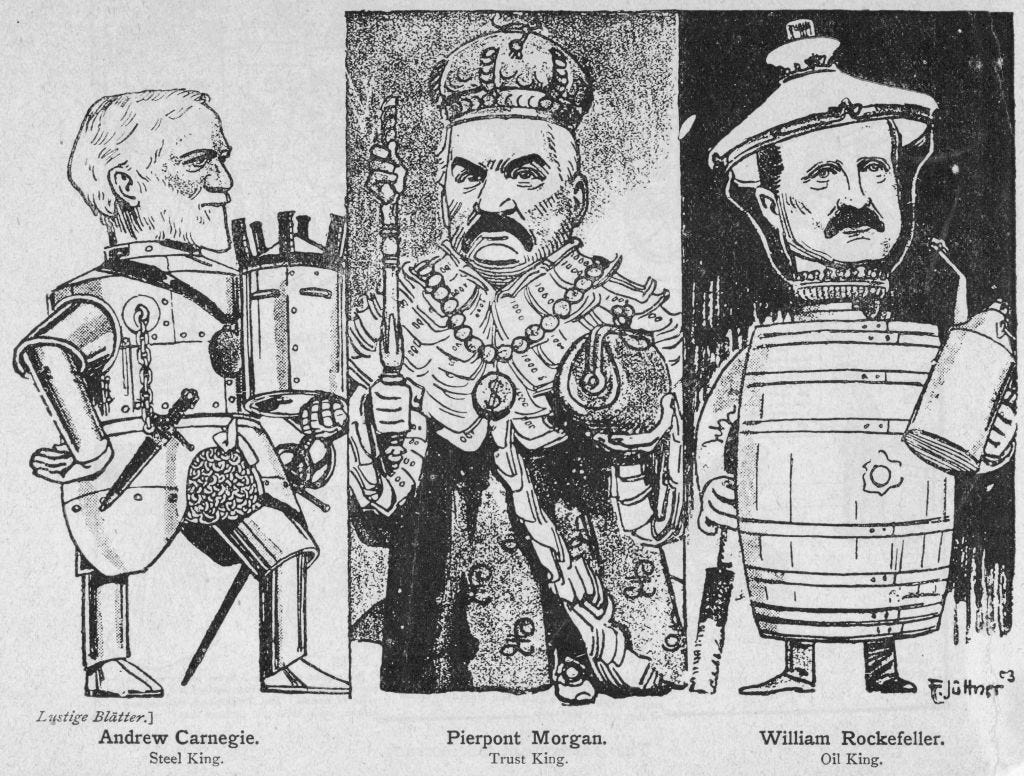

This cartoon from a German newspaper shows two of the tycoons behind the formation of US Steel in 1901: Andrew Carnegie (left) and JP Morgan (center). At right is William Rockefeller, co-founder with John D. Rockefeller of Standard Oil. (Getty Images.)

This post is meant to distinguish a short-term, election-year decision—the Biden administration’s opposition to Nippon Steel’s planned purchase of US Steel—from longer-term industrial-development objectives.

I think a brutally utilitarian calculation lies behind the Nippon Steel decision (which has been widely reported but not yet formally announced). In purely political terms, it may be the only sane thing Biden and Kamala Harris can do. They may see their options as: Interfere with the sale, doing significant but containable economic and diplomatic damage. Or tip the election to Donald Trump, with consequences that could be far worse.

I can’t judge whether they’re right in that political assessment. My purpose is to describe some of the history of such calculations, which put the current one in perspective. And also to distinguish this current Biden/Harris choice from the similar-sounding but very different concept of “industrial policy,” where I think the administration has been acting with US economic interests clearly in mind.

.

1) What’s different about election-year decisions.

The all-or-nothing focus of an election, which is the basis of democracy, always creates hard choices and collateral damage. To work backwards in time:

-1992. People who remember Bill Clinton’s run for the White House 32 years ago may recognize the name Rickey Ray Rector. It is a name I assume Bill Clinton would like to forget.

Rector, a Black man in Arkansas, was sentenced to death for shooting a policeman.1 But after killing the policeman, Rector tried to kill himself with a shot to the head. He survived but was left in a disabled condition likened to having had a lobotomy. In his famous 1993 New Yorker story about Rector, Marshall Frady said that a medical official described him as becoming a “zombie.” According to Frady, when Rector was served his last meal before his execution, he asked the wardens to save the dessert—pecan pie—“for later,” so he could have it before he went to bed. His lawyers argued that he was clearly not competent to stand trial or be put to death.

This happened while Bill Clinton was governor of Arkansas and was in a frantic come-from-behind race in the New Hampshire primary. Clinton went back to Arkansas to be present for Rector’s last-minute appeals and scheduled execution, knowing that as governor he had final power of clemency. In the end, Clinton didn’t grant it, and Rector died by lethal injection. Frady’s piece describes Clinton’s anguish over Rector’s plight—but also the merciless election-year logic of not wanting to appear soft on crime. It was a choice he “had” to make.

-1980. People who know about Ronald Reagan’s campaign against Jimmy Carter in 1980 may recognize the term “October surprise.” This referred to negotiations between the Reagan campaign team and the Ayatollah’s regime in Iran, to ensure that the US hostages held in Teheran were not released before that fall’s election. The reasoning was that the hostages’ plight was a major embarrassment and failure for the incumbent Jimmy Carter, and their release would be a major boost to him. The Iranians complied; the hostages stayed captive; Carter lost; and the hostages were freed immediately after Reagan was sworn in.

There is an enormous literature on this subject, underscoring the Reagan team’s then-secret role. The forthcoming book Den of Spies, by Craig Unger, provides further evidence. (The book’s publication date is October 1—as it happens, Jimmy Carter’s 100th birthday. I have read it and recommend it.) The point for the moment is the contradiction between what was good for the country and what was good for one campaign.

-1968. I was a student during that 1968 campaign, and I remember that Hubert Humphrey’s major political liability was the ongoing catastrophe of the war in Vietnam. As the incumbent Vice President, running against Richard Nixon and George Wallace, Humphrey faced the dilemma of turning against Lyndon Johnson, through public criticism of the war, or not doing so, and sharing blame for it. You can think of some modern parallels.

All the while, peace talks were underway in Paris, which if successful could have been a major boost for Humphrey. In the end, the race was extremely close in popular vote terms. Might a peace deal have made the difference?

We can’t know, among other reasons because the Richard Nixon campaign was secretly but effectively working to sabotage the peace talks. As is the case with the Reagan “October surprise,” evidence has continued to mount up about the Nixon team’s effectiveness in blocking any deal. You can read some of the evidence here and here, describing the campaign’s efforts to ensure that South Vietnamese officials would stonewall until after the election. The results were very bad for the United States, but good for the Nixon campaign.

-2024. By comparison, blocking one steel company from taking over another is small potatoes. It’s not life or death, as these previous cases were in their very different ways.

So why make a comparison? The through-line of these is the reminder of the exceptional ruthlessness of election-year decisions, from cases as individualized as Rickey Ray Rector’s to those of large scale war-and-peace, like Nixon’s about Vietnam. Leaders make choices in these circumstances they might not have otherwise. I think the Nippon Steel blockage will eventually be seen as a medium-intensity version of this kind of trade-off.2

2) Why would Biden block the deal (and Harris oppose it)?

The evidence I’ve seen boils down to this train of thought:

-The election comes down to Pennsylvania. [See: flaws in the US electoral system, chapter 1,045. That’s for another time.]

-In Pennsylvania the Democrats have no margin to spare. Not Harris at the top of the ticket, not Bob Casey for the Senate, not Congressional candidates.

-The Steelworkers are very important in Pennsylvania, and they oppose the deal.3 So do two Senators who are on the ballot this year in seats the Democrats can’t afford to lose: Casey in Pennsylvania and Sherrod Brown in Ohio.

-To top it all off, Donald Trump is already against this deal. It’s all too easy to imagine the “they’re selling out America!” ads and speeches the GOP would use to blanket the “Blue Wall” states. It’s all too easy to imagine their xenophobic framing.

QED. From Biden and Harris on down, the Democrats must have felt this was a choice they “had” to make. And the damage is less immediate and vivid than the other choices I’ve mentioned, and countless more.

3) What’s the harm in blocking the deal?

There is coverage of this decision everywhere these days. To boil it down:

-From the region’s point of view, there’s no reason to be confident that a future without new Nippon Steel money would be more profitable or stable than the alternatives. For instance: It matters to Pittsburgh that US Steel has its headquarters there. Nippon has promised to move its US headquarters to Pittsburgh, and to keep the US Steel name. Without the deal, who knows? The same goes for the investments Nippon Steel has committed to make and the factories it has said it would keep open.

-From a factory-survival point of view, the $14.9 billion bid from Nippon Steel was the highest offer for US Steel, ahead of the US firm Cleveland-Cliffs. Absent the Nippon deal, will Cliffs or some other company buy at a discount? Will it promise to keep factories running where they are now? Maybe. It’s easy to think of examples of things not working out that way.

-From a national-interest point of view, the argument that the sale might raise “national security” concerns seems very thin. According to a story today in Reuters, the main “security” concern was that foreign ownership might hinder the supply of steel for crucial US defense and infrastructure needs. According to Reuters, an American lawyer for Nippon Steel replied:

If the government is "truly worried about maintaining steel supply here in the United States, the real solution is not to block this deal, but instead to use the CFIUS hammer to ensure that Nippon Steel makes and maintains such investments," he added. [CFIUS is the committee that scrutinizes foreign investment in the US.]

-On military and strategic issues, Japan is as tightly connected to the US as any other ally—exceptionally so, since Japan’s post-WW II constitution limits its own “Self Defense Force” and establishes the US as a guarantor. US troops, ships, aircraft, and munitions have operated for decades on Japanese soil, in coordination with Japanese civilians and officials. With those connections, it’s hard to imagine the national-security threat of changing ownership of what is, in global terms, a smallish steel company.4

And the Japanese, understandably, don’t like it.

Nor do most people who know about business. As a NYT story this week put it:

“I don't know any economist that thinks this would be good for the U.S. economy — to block the merger — and the national security arguments for it seem equally weak,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard economist who worked in the Obama administration. “The United States has emphasized friend-shoring… This goes against the spirit of that approach.”

4) What is to be done?

Remembering the difference between pure politics and industrial policy.

Why do I set up a steel-policy story with examples from a death-penalty case and thwarted peace negotiations?