Election Countdown, 38 Days to Go: What Is Wrong With Our Leading Paper?

A view of public life as political circus. And the ongoing damage that view does.

A Manhattan newsstand on a springtime morning in 1970, with the day’s supply of New York Times copies to be sold. Now newsstands are gone, and the Times’s business model has very successfully adapted to the completely different media-economics realities of a new era. But its model of political coverage is out of sync with the realities of this age. (Photo Walter Leporati/Getty Images.)

This post is about the press again. It will be organized around one email, and then one tweet. After that, another look at the question: At this point, does it even matter what the press does?

1) An email from James Gleick.

The reading public knows James Gleick as a prolific and acclaimed writer, mainly of articles and books that make the arcana and personalities of science and technology comprehensible and engrossing. His influential books include Chaos (which introduced many readers to the idea of the “butterfly effect”), Genius, The Information, Faster, and others. He is also a successful tech entrepreneur. I know him as a friend.

Earlier in his career Gleick spent a decade as a reporter and metro editor at the New York Times. Yesterday he sent me an email about the NYT’s coverage of an interview Kamala Harris did this past Wednesday with Stephanie Ruhle, of MSNBC. With his permission I quote his note.

Gleick is writing about a start-to-finish snarky article by the Times’s Reid Epstein, presented on the paper’s site this way:

Gleick writes:

What do you expect from a piece headlined “3 Takeaways from Kamala Harris’s Interview …”? Me, I expect the three most interesting or important things Harris said about her plans, policies, positions. Perhaps contrasted with Trump’s views or lack thereof on the same topics.

[JF note: In this interview on economics, Harris was vaguer and less in-command sounding than she is on topics more in her wheelhouse—law-and-justice issues, reproductive rights, legislative strategies, even international policy after nearly four years as vice president. But she was much more substantive, and infinitely more truth-bound, than Donald Trump on similar topics, and she provided the policy-related information Gleick says readers would have liked to know more about.]

Not in the modern New York Times. The Times is obsessed above all with Harris’s unwillingness to sit for an interview with the Times. Until she does that, she will be hammered for not doing enough interviews, and her interviewers will be hammered for not asking the right questions.

So what are the “3 Takeaways” if not things Harris actually said? [JF: This is the Times’s list.]

“Harris had roundabout answers …”

“She avoided …”

“A hard-hitting Harris interview is still to come” (with us or it doesn’t count).

This is really unconscionable in the news pages. As is this astonishing sentence: “For the vice president, speaking with Ms. Ruhle was roughly in the same ballpark as Mr. Trump having one of his regular chats with Sean Hannity of Fox News.” I’m trying to imagine Ruhle’s reaction to that.

Along the way the Times lets us know what they think are useful questions for Harris and shows the political press at its worst:

"She said nothing about why voters think Mr. Trump and Republicans would be better on the economy.” (Actually, of course, some voters think that, and some voters think the opposite.) Harris’s job is to tell us why she would be better for the economy, with specifics. It’s not to guess why some people think otherwise.

"Ms. Harris skated past Ms. Ruhle’s question about where Democrats would find the money for such proposals without addressing her party’s Senate prospects.” This is a stupid gotcha sort of question. Harris’s job is to tell us what she plans to do. We all know that if she has a hostile Congress she won’t be able to do everything she’s proposing. So what’s the question she “skated past”?

And finally the big question—the one the Times is apparently dying to ask [JF: but which Stephanie Ruhle, appropriately, did not deem relevant]: “what, if anything, she knew about Mr. Biden’s physical condition or mental acuity as his own campaign deteriorated.” That would be a “tricky” question, so it must be good, eh?

Gleick says that he was looking for the “takeaways” that would matter to readers, voters, citizens—and on which Harris did provide some guidance. Indeed, earlier that same day she had given a substantive speech in Pittsburgh on “industrial policy” and other economic plans, and released an 82-page book of economic-policy proposals.

The actual Times story offered “takeaways” strictly of use and interest to political insiders and consultants. That’s a big difference, and one that the Times’s political team seems not even to register, since the emphasis on politics-as-spectacle runs through virtually everything the paper presents about US public life. Two more examples just from yesterday (and again with the reminder that the “hed and dek” of a story, the headline and sub-head, are all that most readers will ever have time to see):

Here immigration policy is framed purely as image-management (as longtime newspaper editor Mark Jacob explains). And below, a genuine news scoop by the Times’s Annie Karni and Catie Edmondson is muffled in one more story framed as image-management.

(The under-heralded scoop is their amazing revelation about Derrick Anderson, a Republican Congressional candidate for an open seat in Virginia. Anderson’s campaign has produced photos of the candidate, who happens to be unmarried and have no children, with a woman and three girls who would appear to be a “family” but are not related to him at all. That’s not in the hed or dek, and is first mentioned six paragraphs down in the story.)

Two other veteran Times staffers who have written in puzzlement about the current, often-snarky, political-consultant guiding mentality at the paper are my friend Tom Redburn, who spent decades as a Times reporter and economics editor, in his Redburn Reads; and James Risen, a longtime investigative and national-security reporter for the paper, in The Intercept.

1A) A note about Stephanie Ruhle.

As James Gleick points out, the NYT piece on the MSNBC interview took a catty swipe at the interviewer, Stephanie Ruhle. Like most people who succeed as TV regulars, Stephanie Ruhle has her own distinctive schtick and persona. Some people may be put off by it; I think she’s very good at what she does.

And like most people at MSNBC, Ruhle is crystal-clear in calling out Donald Trump’s lies and the 99% BS quotient of his policies. We know how she’s going to vote—she has told us, and explained why.

But she is not like Sean Hannity—nor Fox’s Jesse Watters or the now-exiled Tucker Carlson. She differs in that she respects the boundaries of established fact and won’t lie or pander to help “her side.” (If you disagree: Please send me an example of her doing so.) And relevant in this case, Ruhle knows about the topics she was discussing with Harris: economics and finance. Before getting into journalism, she worked in banking for more than a dozen years. By contrast, Fox’s Hannity and Watters, like Rush Limbaugh before them, have spent virtually their whole careers in talk radio and partisan TV.

So for a Times reporter to frame Ruhle, working in a topic she knows, as on a par with Hannity nodding along with Trump’s delusions and rants, is a revealing “both-sides” tell. These things are different. Our leading paper reflexively—and explicitly—groups them as the same.

2) A Tweet on the ‘industry’ of criticism.

The Xitter thread I have in mind started a week ago with Dan Froomkin, of the invaluable Press Watch site. He commented on a Fresh Air interview with Maggie Haberman, the well-known Trump chronicler for the NYT, about the difficulties of covering a man who lies and fantasizes so relentlessly.

In the interview Haberman told Fresh Air’s Dave Davies many things that Froomkin (and I) would agree with. For instance, how Trump’s cognition had deteriorated. And how the press’s rules and instincts “were not built to deal with somebody who says things that are not true as often as he does or speaks as incoherently as he often does.”

But she also said something that Froomkin called out, even though Dave Davies did not follow up on it. It was her claim that the press “does a very good job covering Trump,” and that people who felt differently came from “an industry, bluntly, Dave, that is dedicated toward attacking the media … [and] undermining faith in what we do…. I'm talking about criticism on the left.”

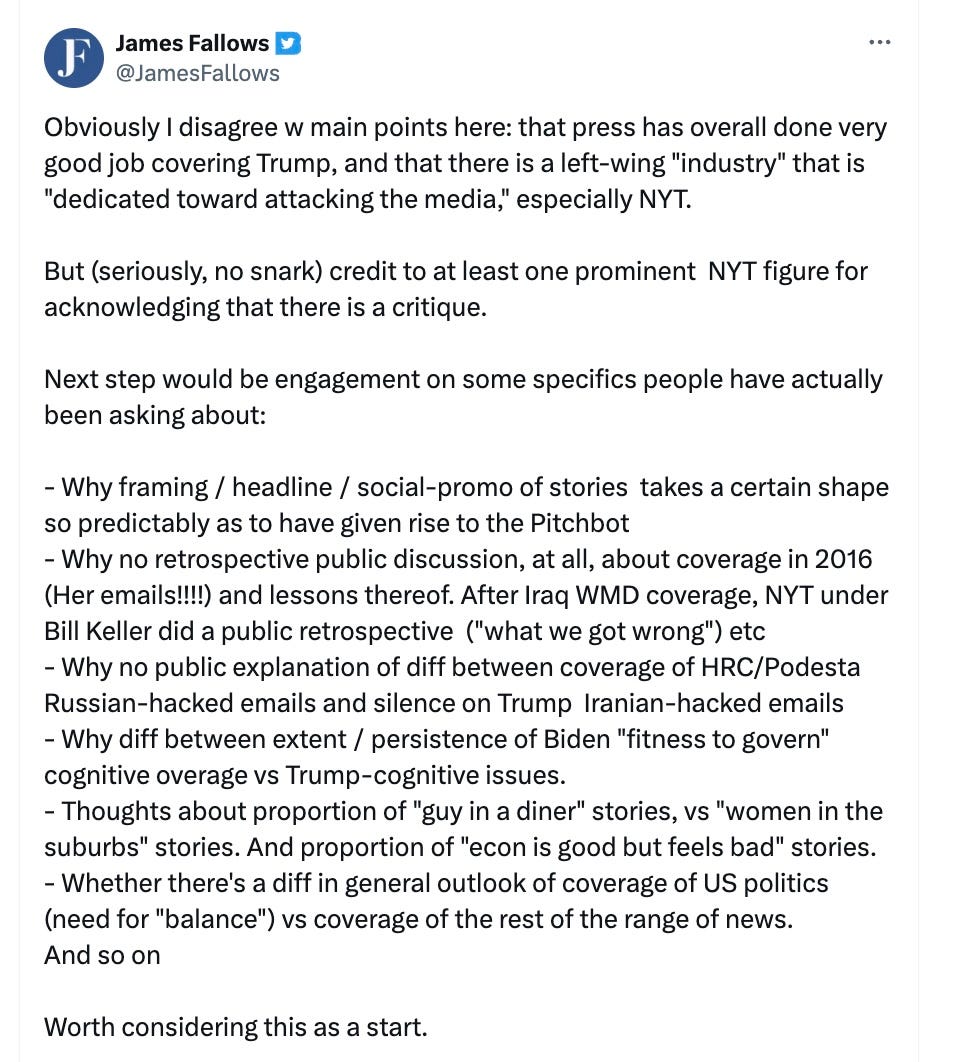

I thought it was good news that Haberman would even acknowledge such criticism. Institutionally the paper almost never engages at all. The bad news was that she caricatured it as an “industry” coming from “the left.” I did a Tweet about the good and bad this opened up1:

Why do I offer this? To underscore the only-increasing importance of a bad mistake the Times made seven years ago, when it abolished its “public editor” role. Here’s a reminder of the timeline, which has ended up in a Catch-22:

2003: The Times introduced this role in 2003, under then-Executive Editor Bill Keller, after several controversies about the paper’s coverage. (Including hyping the WMD threat from Iraq.) The first public editor, the estimable Dan Okrent, introduced himself in what proved to be a prescient way:

“Reporters and editors (the thickness of their skin measurable in microns, the length of their memories in elephant years) will resent the public second-guessing…

“But those are their problems, not mine. My only concern in this adventure is dispassionate evaluation; my only colleagues are readers who turn to The Times for their news, expect it to be fair, honest and complete, and are willing to trust another such reader -- me -- as their surrogate.”

2003-2017: Over the next 14 years, some Public Editors were stronger than others. My two favorites were Okrent and Margaret Sullivan. But all shared a power whose importance grows now that it has been taken away: They had standing to ask questions and get answers from reporters and editors about their judgment calls.

2017: When then-publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. (father of current publisher A.G. Sulzberger) announced the end of this position in 2017, he claimed the paper had “outgrown” it. Why? Because readers and the Twitter/Facebook universe would “collectively serve as a modern watchdog.”

2017-now: Hah.

The difference now is that leaders at the paper virtually never acknowledge, engage with, respond to, or otherwise answer questions from members of this “modern watchdog” group—including readers or online commenters who are not their enemies but want them to be better. The few times they do respond, it’s with sub-tweeting, as in a recent essay by A.G. Sulzberger, or with straw-man caricatures, like the supposed “industry” of criticism. I fear that is what they tell themselves inside.

In its coverage of any other power-establishment, the Times would be the first to note that institutions that are neither transparent, nor accountable, are asking for trouble. The news system is not transparent. (We have no idea who writes these headlines or decides on story-play.) It is not accountable. (See above.) This matters for Boeing and the banking system and pharmaceuticals and everywhere else. It matters for the news.

3) Who cares?

How does any of this matter?