Election Countdown, 258 Days to Go: The New Politics of Place.

More opportunities are coming to places that need them.

A 1930s packing house label from a long-defunct operation in the small town where I grew up, and where my first job was in the orange groves. The prospects of better weather, better possibilities, and a new start were all part of what drew my parents from the East Coast to California during the great post-World War II migration. Several new reports show how the politics-of-place is changing now. (From the Huntington Library, via the wonderful Fruit Crate Labels collection at the Los Angeles Public Library.)

This post is about some of the longer-term forces that shape Americans’ lives and communities, and could also shape American politics this fall. My purpose is to introduce several interesting new entries on what I think of as the geography of opportunity. And to point to recent federal policies that appear to be working as planned.

‘Should we stay or should we go?’ The enduring American tension.

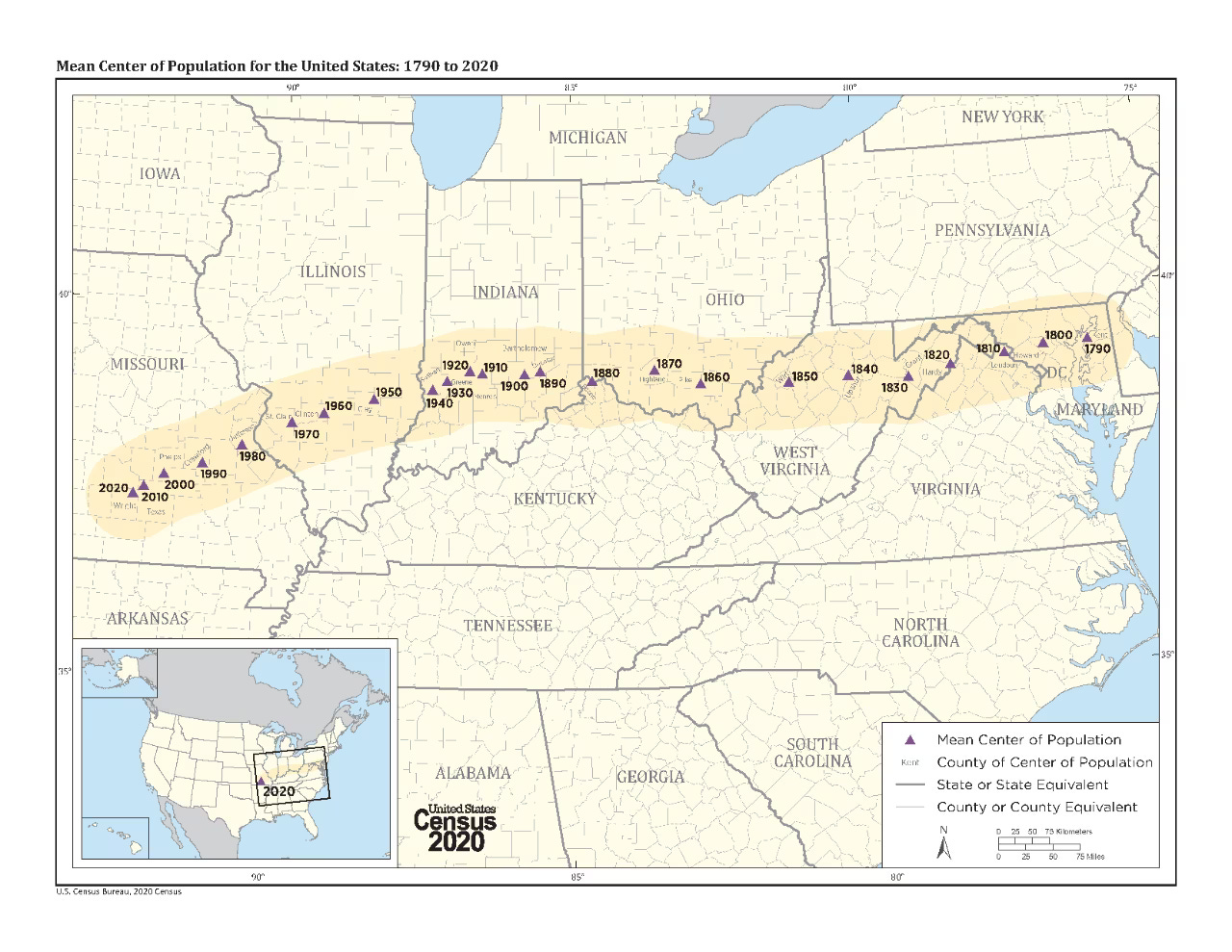

Place has always played a major role in Americans’ personal sagas and public beliefs. The design of the US Senate guarantees that it plays a major part in national politics as well.1 All Americans except indigenous people arrived from elsewhere relatively recently. Some by choice, some from desperation or necessity, some when compelled. Through the centuries since the 1600s they’ve continued to move to different places within the continent, mainly south and west.

From the Census Bureau, decade-by-decade track of the geographic center of US population, from 1790, when it was just east of Baltimore, to 2020, in southern Missouri.

Through those centuries, settlement patterns and family histories have reflected the tension between two powerful, opposing aspects of the American Dream. On one side, the reasons to stay, in the place where you belong. On the other, the reasons to go, to some place different, some place “better.” Every great American novel has encompassed these tensions. Nearly every family story in America has as well.

Rates of movement and migration have gone up and down over the country’s long saga, and have been slowly falling through the lifetimes of most of today’s Americans.2 The dual, contradictory reality of our times includes the pressures to stay and to go. Many people want to move someplace else, and do. (As witness the growth of the Sunbelt and the suburbs). But an even larger number don’t want to move away, or can’t. For instance, according to the latest (2020) Census, most Americans in their mid-20s lived within 10 miles of their childhood homes. Only one in five lived more than 100 miles away.

These dual realities mean that providing “fair” opportunity in the country requires two opposite-seeming forms of help:

-Making mobility easier, for people who want or need to go, as the US has done in countless ways from the Northwest Ordinances onward.

-But also restoring opportunity for people who want or need to stay, as the US has done in a mainly patchwork, “pork barrel” way from the beginning.

It’s the patchwork part that may be changing now, toward something more “strategic” and planned. The illustrations are below, and their cumulative point is that we may be living through a high-stakes federal bet that at least initially is paying off.

Remembering ‘forgotten’ America.

Through the Trump era, we’ve heard nonstop about the political ramifications of people and places that feel left behind. We can debate how much regional inequity, as opposed to pure resentment and tribalism, was the basis of Trump’s MAGA support. But the unequal “geography of opportunity” is real.

Here are illustrations of recent movement toward bringing more opportunity to places that feel closed-down.

1) ‘A New Story About the Rust Belt.’

In this new report from Brookings Metro, John Austin and Mark Muro explain why explicitly place-based, unashamedly “industrial policy” investments by the Biden administration were starting to bring a tech-and-manufacturing revival to battered “Rust Belt” communities.

Muro and Austin explain the logic behind the projects, and what obstacles troubled Midwestern communities still face. But as the title of their paper indicates, they argue that the region’s trajectory may be changing. The title is: “CHIPS and Science Act programs are writing a new story about the Rust Belt.” Their essay concludes:

It remains easy to misperceive the Midwest as merely “flyover” country, with industries that mattered to the last century’s economy but not to today’s tech-driven one. However, the geography of the nation’s new industrial strategy demonstrates that the region and its innovation infrastructure are reemerging as key focal points for the desire to invent, commercialize, and scale-up the technologies that will advance American competitiveness.

This is worth reading.

2) Federal investment going where it’s needed.

Also from a group of authors3 with Brookings Metro, a report demonstrating that federal investment is going where it’s needed in a more fine-grained way. This report shows, not surprisingly, that private tech investment has generally gone to “winner” parts of the country. But then it documents how Biden-era “strategic investments” by the federal government—in clean energy, semiconductors and electronics, biotech, advanced manufacturing—were going disproportionately to “have-not” parts of the country.

For instance:

Counties defined as “economically distressed” account for 8% of the US GDP but have received 16% of these new “strategic investments.”

“Micropolitan” areas, with populations below 50,000, have been disproportionately left-behind. But they have received fully 50% of the “strategic investments,” again a disproportionate share.

Federal investment has been most effective over the decades in leading the way for private firms. That has been the pattern in agriculture, aerospace, info tech, bio-tech. And, yes, petroleum. The report argues that federal investment in this era’s growth industries is already bringing private investment to left-behind areas. Check out the report for details.

Again worth reading, for evidence that a federal policy may actually be working as intended.

3) The thinking behind that federal investment.

Let’s come back once more to Brookings. Last month Lael Brainard, director of the White House’s National Economic Council, gave a speech there about the rationale behind the administration’s place-based policy. Mark Muro of Brookings wrote about it here, and you can read the whole text from the White House site.

Brainard used examples from downtown Milwaukee, from Allentown PA, from Baltimore, and from elsewhere to illustrate that federal investment has been directed in sync with local initiatives and innovation. “Good economic policy starts with the basic insight that communities are where economic development happens,” she said, “where people connect with jobs, develop their skills, start businesses, make their homes, and raise families.” And:

Economic growth takes root at the local level. From that basic reality comes an important insight: we are more effective at growing the economy when we lift communities up rather than leaving them behind.

This may not seem startling, but it’s a refreshing change from saying, as in a catechism, that tax cuts or “China tariffs” are the automatic way to build economic opportunity.

4) ‘Reimagining Our Economy’

We move at last from Brookings to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Late last year it released a report from a multi-year effort by its “Commission on Reimagining Our Economy,” or CORE. (I was on that commission.) Today in the New York Times one of the commission’s co-chairs, Kathy Cramer of the University of Wisconsin, and an Academy senior program officer, Jonathan Cohen, have an op-ed based on the report, about a particular aspect of “left-behind” America.

Cramer and Cohen write about one aspect of the CORE project4: a set of “listening sessions” with, especially, working-class people around the country. I can’t stress enough how different these sessions were from standard “guy in a diner” interviews. They never started with national politics, and only rarely ended up there. Instead they were about people’s personal stories: Their successes, their challenges, their ideals, their realities. They were in the spirit of Studs Terkel’s Working interviews, 50 years ago.

The op-ed today stresses one aspect of economic reality left out of the currently buoyant statistics: how precarious many people feel their situation to be. Families are one flat tire, one workplace injury, one bad fall, one sick child away from ruin. This is the reality that novelists seize on to capture the economy of any era. Think of Dickens, think of Victor Hugo, think of Theodore Dreiser or Upton Sinclair. The report makes the consequences vivid, and suggests practical solutions.

More hometown orange-crate art, from the two-decade period of the 1920s and 1930s in which California’s population doubled, as people moved in to get a new start. (LA Public Library collection.)

Here is one final place-based recommendation: It’s a great article by Deb Fallows, about ways in which she is changing her mind about Florida, after an unexpected multi-month deployment there. It features a local newspaper doing its best to engage people in their civic life.

And one more: A trenchant and important essay by fourth-generation Floridian Billy Townsend, about why his native state needs all the help it can get. I promise you that both of these Florida pieces are worth reading, back-to-back.

And another place-based dispatch is upcoming: a podcast with my friend Tom Ruby, about what outsiders don’t understand about life in rural Kentucky.

Soon I’ll get back to the day-by-day politics. The themes today are changes on the year-by-year and decade-by-decade scale, through which people in our era may be shaping the nation’s course.

My former mentor Charlie Peters used to say that if a point is worth making once, it’s worth making over and over again. In that spirit: Any time we talk about Congressional “dysfunction,” we should talk about the radical change in geographical math between the Founders’ era and ours.

When Madison, Hamilton, et al worked out the compromises between big states and small states that led to all states having the same two votes in the Senate, the gap between biggest and smallest was not that extreme. In the 1780s it was about a ten-to-one difference, between the most populous (Virginia) and the least (Delaware).

Now the gap is about 68-to-one, between California (nearly 40 million people) and Wyoming (under 600,000). If big-state negotiators as hardheaded as Madison (VA), Hamilton (NY), Franklin (PA), Elbridge Gerry (MA), et al had been working with a 68-to-one difference, it is impossible to imagine that they would have agreed to the “Great Compromise” that led to our current Senate’s setup. Gerry, namesake of the Gerrymander and an important figure at the Constitutional Convention, finally refused to sign the Constitution because of concern with its various structural flaws.

We see the results of those flaws now, when the combination of Senate filibuster and unbalanced Senate representation mean that Senators elected by a tiny fraction of the population can block measures with very strong national support.

What can we do about the Senate’s structure? In practical terms, nothing—other than continue to engage in state elections and know that states’ political complexions can change.

The American Community Survey analysis from the 2020 Census said that annual moving rates within the country have mainly been going down since 1948, despite the dramatic growth of the West Coast, the Sunbelt, and suburbia in those same years. More recent figures: In 2006, some 16.8% of Americans moved to a different house or apartment. In 2019, only 13.7% did.

You can think of both good and bad reasons for the long decline in annual-moving rates. My parents lived (with me in tow) in seven different apartments or houses, in four states, by the time I started first grade. This was less “mobility” than it was churn, and few families would choose it now. On the other hand, some people today who would like to move end up feeling more stuck than before—because of the cost of moving, the loss of social-networks of support, the nightmares of the real-estate market, family obligations and family ties.

The authors are Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, Lily Bermel, Lisa Hansmann, Mark Muro, Ryan Cummings, and Brian Deese.

The project had four related-but-different parts: The listening sessions, which will be archived by the Library of Congress; an innovative set of “CORE score” rankings to mark how communities were doing on the main markers of civic well-being; a wonderful photo-essay book called Faces of America, in the spirit of the famed New Deal era photos from the Farm Security Administration; and its official report, with detailed recommendations. I endorse them all.

Jim In 90 years my ‘places to go’ have included Egypt, Congo, and Chile, which consumed over a decade of my life. Domestically, I have moved between Philadelphia, Washington, CT, NY, and NJ.

When I returned from my foreign residencies, I found myself in the midst of ‘Rust Belt’ woes, in which North/MidWest were discarded, and South and West were the places to be.

Of course, as a historian, I was aware of how the pattern was to go West back in the 18th/19th centuries, while textile businesses went South, though Northerners didn’t.

I recall when major corporate headquarters (before the internet) were locating out of New York and Chicago for suburban locales (or even farther).

Now with Internet and working at home, the geographic ‘living space’ has become even more flexible, when even Silicon Valley has been dispersing.

I am comfortable in my East Coast quadrant, as is most of my family. Personally, I am affected by the politicalization of America. My wife and I would shudder at the prospect of being in a big red state (like Florida, Alabama, Texas, Wyoming), where our views about the soul of America would not be welcome.

My granddaughter, who loves being at UCLA, speaks of returning East after graduation. Who knows? Staying close to family is a top priority for me and Georgia. Our children are all in the Eastern quadrant, as are all of our grand kids, except for the UCLAn.

My hunch is that retirement will be a major consideration for folks seeking better weather and/or taxes. Other than that, I foresee less major job moves and more living environment considerations, as the Internet provides considerable flexibility.

Housing is and will remain expensive. This could be a major consideration, since it is the largest annual expenditure for most individuals.

In my family, L. B. R. Wheelock did flee New York in 1833 because of ‘an affair of the heart.’ He founded Wheelock, Texas, a small town in the hinterlands. To his credit, he wasn’t buried there. Years ago I visited Wheelock. It’s river diverted about a century ago and there are only a few residents, mostly old women with their stockings rolled down. I doubt that we will retire to Wheelock.

Great piece, as usual! One thing inhibiting migration, which you allude to indirectly: There are still a lot of homeowners whose homes are "under water" compared with their mortgages. So they can't move (I can suggest a fix for this). Opposite problem in some parts of CA: home values have increased so much that older folks won't move because of CA taxes that would then be due; they wait for their kids to inherit the house and get a stepped-up basis. Finally, consistent with what you've written here (and maybe the work of the authors you cite), there is good data now on impact of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. A huge disproportion of the announced project numbers, total billions of contemplated dollar investment, and scores of thousands of new jobs is/are all happening in red states or red Congressional districts within states. Various reasons for that, of course, including lower average wages and faster permitting and less NIMBYism than in more prosperous and densely populated areas. But the phenomenon seems real, and a powerful reshaper of the US economy!