Election Countdown, 198 Days to Go: A Civic Example to Follow.

Political memories fade. Bob Graham's unusual, inspiring story should live on.

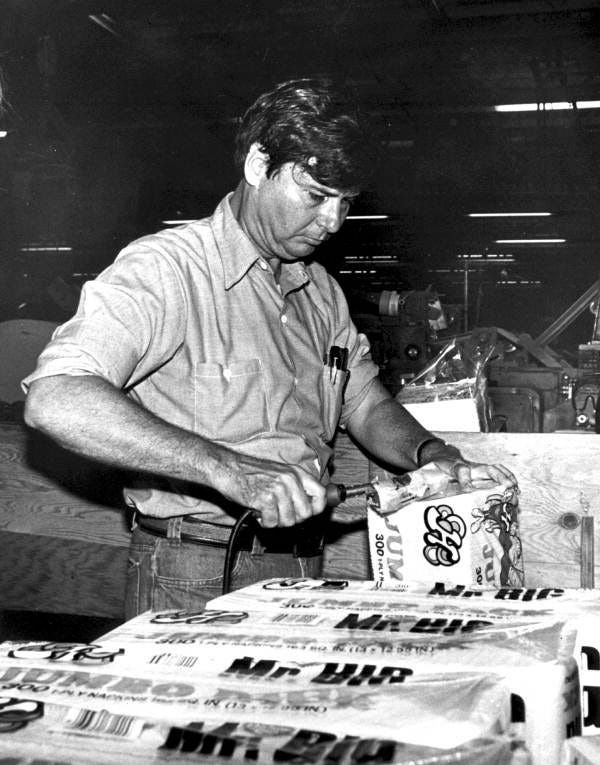

As a young Florida state senator in the 1970s, Bob Graham spent full 8-hour shifts working a variety of jobs around the state, preparing for his successful run for governor in 1978. He continued the “Workdays” through his two terms as governor and three as US Senator. Here he is shown sealing packs of paper napkins at a pulp-and-paper plant. (All Workday photos from Florida State Archives.)

By the time Bob Graham died six days ago in Florida, at age 87, he had been in failing health and out of the public eye since a stroke four years earlier. I imagine that most people outside Florida, and outside the specialized world of politics, would by now have a hard time remembering just who he was and what he stood for. Even this past week’s prominent obituaries came and went, amid the distracting squalor of the Trump trials.

That’s inevitable. But it’s too bad, because—especially in this graceless moment in public life—an example like Graham’s is surprising, instructive, and also entertaining. I had no special connection to Graham: I met him several times, interviewed him during the Iraq war years, was on a few TV shows with him. But I was learning about politics when he was coming to power. This post is about some of the things I learned from watching his career, and what the Bob Graham story can still tell us now.

What campaign operatives remember about Bob Graham.

More than 20 years ago, Graham made a brief run for the presidency. This was the 2004 race for the Democratic nomination that John Kerry eventually won (before losing to GW Bush in the fall), and for which Howard Dean was unfairly immortalized because of his “victory scream” after taking the Iowa caucuses.

Graham didn’t get nearly as far as Dean, though he had entered the race with seemingly a lot in his favor. Through his two terms as governor of Florida and three in the US Senate, Graham had been by far the best-liked politician in the state. For instance: at the end of Graham’s time as governor, his statewide approval rating was above 80%. (Remember, this is Florida, and he was a Democrat.) But he had trouble raising money in the crowded presidential-primary field. And the plain-talk speaking style that had worked so well in retail-level Florida campaigning came across as wooden and tedious in national events. Graham was the first Democrat to drop out of the race.

Also among his problems was a media-herd obsession similar to what befell Howard Dean. Through his career, Graham had always carried little notebooks with him. He would frequently take them out to compose precise handwritten records of every single thing that was occurring. What he had for lunch, what someone told him, what he told other people he would do.1 By the time he ran for president, Graham had more than 4,000 of these small, neat books, which he’d kept in careful order.

In much press coverage from that era, the notebooks became shorthand for the “wacky” factor about Bob Graham. A sample 2003 article in the Washington Post will give you the idea (below2). For the political press his wackiness and “eccentricity” became the counterpart to Dean’s "scream,” and Hillary Clinton’s emails. They became the Graham meme, as we’d put it today. What a weirdo!

But here are three other elements that I think should make up the real, lasting Bob Graham meme.

Bob Graham, while in office as governor, handling sod with crew members identified as Willie Lee Rasberry (left) and Samuel DeLoach at a road-widening project in Tallahassee.

1) A genuine curiosity about different walks of life.

Bob Graham had family connections. His father, Ernest “Cap” Graham, had been a Florida state senator and a successful dairy farmer. His much older half-brother, from Cap Graham’s first marriage, was Philip Graham, famed as publisher of The Washington Post and husband of publisher Katharine Graham. In the next generation Bob Graham’s daughter, Gwen Graham, became a Florida legislator and (unsuccessful) candidate for the Florida governorship.

So Bob Graham didn’t grow up hard-scrabble. He went to the University of Florida and then on to Harvard Law. But his career-long commitment to “Workdays”—full 8-hour shifts at unglamorous “regular” jobs, with press allowed in only briefly for photos—started as a publicity gimmick. Eventually these were seen in Florida as a sincere demonstration of humility, curiosity, and the kind of fellow-feeling we now associate with World War II movies.

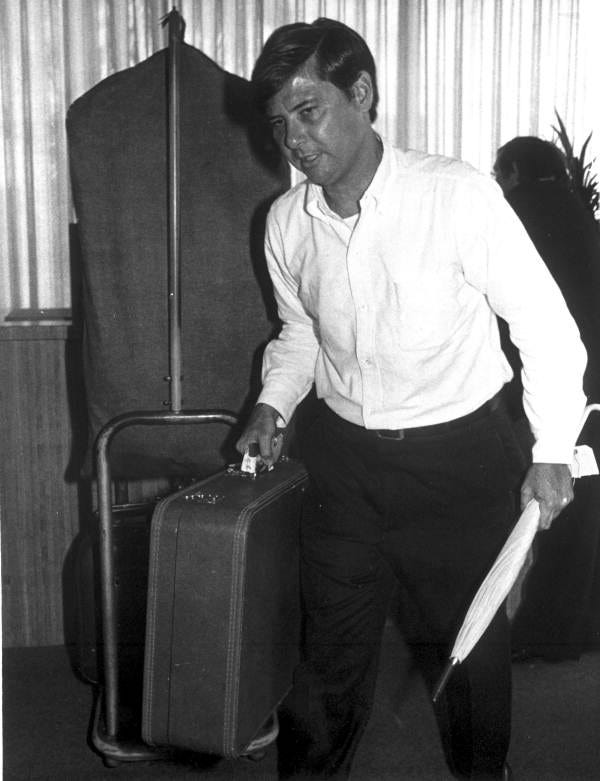

There’s a whole photo archive of Graham’s Workdays on a Florida state archives site, here. They show a sampling of his countless roles, from circus clown to plumber to teacher to construction worker. I have fun imagining some of today’s talk-show politicos, with Harvard Law/ Yale Law pedigrees like Graham’s, putting in eight hours as a bellhop, as he did.

Bob Graham, looking like a student but age 40 at the time, on his day in 1977 as bellhop in an Orlando hotel.

Graham carried out more than 100 Workdays while running for governor—and then another 300-plus while in office as governor and then US Senator. This had to have left a mark. Graham’s steady record as Florida’s most trusted public figure must have reflected a broad sense that he knew the people of the state, and they knew him.

2) A deep, practical belief in civic education.

The main time I talked with Bob Graham in person was 15 years ago. This was long after his presidential campaign had fizzled out and he had retired from the Senate. We were at an event together. I listened to him address a small audience, and then later I interviewed him about the theme of his talk, which had become the central theme and passion of his last decade in public life.

This theme was the importance of teaching Americans about their own country. In other words, the tedious-sounding but ever more pressing need to educate people on “civics.” In a system as complex and contradictory as ours, it’s not something people automatically learn on their own.

I put “civics” in quotes because the word itself now seems so quaint. But that stodgy outdatedness is what Graham had determined to fight. In talks and writings, he laid out the practical implications of citizens not knowing what citizenship means. What if voters don’t understand what a president is supposed to do — and not do? How the Supreme Court works? What the First Amendment means? What impeachment is supposed to be for? What “compromise” involves? In the news each day we see people who understand none of these things.

As Graham wrote in an op-ed in the Tampa Bay Times back in 2017:

If you want to know what happens in government when voters are uninterested, diverted or uneducated about the skills of effective citizenship, look no further than Washington and Tallahassee…

What is going on? One significant, under-the-radar reason is that since the 1970s there has been a virtual collapse in the teaching of civics. Two generations of Americans and Floridians have finished their high school education with little or no instruction in what it means to be a citizen in a democracy. They have never learned the centrality of civility and reasoned compromise in a democracy or the rights, responsibilities and skills necessary to be an effective citizen.

Someplace I have the recording of my talk with Graham that day. If I were as organized as he was, I’d have it in hand and be quoting from it now. I know that he spoke in detailed, practical terms about how to make Americans savvier about their unusual system of government, and more passionate about their responsibility as shapers of democracy, not just powerless objects.

In the political and media landscape of the cable-news era, it was brave of Graham to make “civics” his major theme, precisely because it’s so “worthy”-sounding and dull. But Graham gave speeches about it; he wrote a book called America, the Owner’s Manual; he set up a Center for Public Service at the University of Florida; and generally he lived his 70s and early 80s as if empowering the citizenry was the way he could best help strengthen the country.

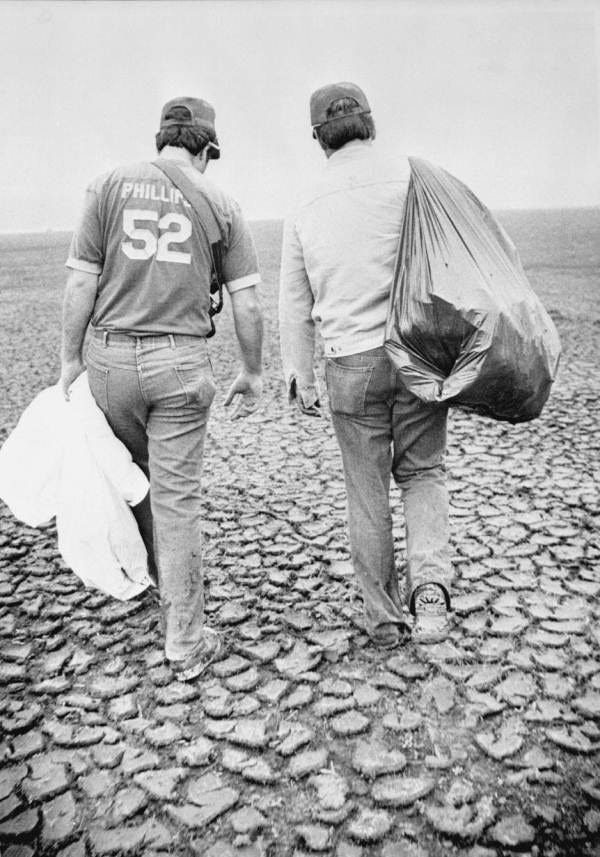

US Senator Bob Graham (in cap), then age 64, during his day as a baggage handler for USAir.

3) Prescience and courage on war and peace.

Early in the GW Bush administration, Bob Graham was chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Graham and his House counterpart, Rep. Porter Goss (a Republican), announced a joint House-Senate inquiry into what had gone wrong.

Through the next year, as the Bush administration ceaselessly drove toward war in Iraq, Graham became a clear-eyed and forceful opponent. When the decisive vote to authorize war came to the Senate, on October 11, 2002, it went through in a landslide, 77-23. Many Democrats who voted Yes that day soon came to regret it. Their names are well known. For starters: Joe Biden, John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, Chuck Schumer. The names of those with the foresight and grit to make the unpopular No vote that day—and explain why—should be just as familiar to us. Prominent among them was Bob Graham.3

What swayed Graham, generally a foreign-affairs centrist who had voted in favor of the Gulf War of 1991? Graham said that the intelligence committee inquiries made him skeptical of the administration’s cherry-picked case for invading Iraq, and fearful about the long-term effects of this “discretionary” war.

“The information that supported their case came smoothly out of the pipeline,” Graham told the Sun Sentinel in Florida the day after his vote, when asked whether his anti-war stance might be a political liability. “Information not consistent with their view of the world, you had to rattle the pipes to get it out. I felt a lot of my colleagues were voting without having all the facts in front of them.”

Another ‘what if?’

Many prominent Democrats now have to squirm when looking back on their Iraq decisions in 2002. Bob Graham was not one of them. Another whose Iraq views look better with the passing years is Al Gore, who in September, 2002, shortly before the fateful Congressional votes, gave a major, fully argued, anti-war address.4

Gore’s prescience about Iraq is one of countless reasons to ponder how history would be different, had he been in charge. Which in turn leads us back to Bob Graham, and a final what if.

In the summer of 2000, the Sun Sentinel had this headline: “Graham’s Star is Fading as VP Contender.” The context was Florida’s importance in the upcoming Bush-Gore presidential race—and whether Gore’s choice of a running mate could make a difference there.

The “Star is Fading” story said that the Gore team recognized Graham’s in-state appeal but was looking for someone more exciting, and younger5. They ended up with Joe Lieberman. The close of the story had these haunting lines:

Jim Kane, editor of the Florida Voter political newsletter, said the removal of Graham from the ticket would probably put the state in Bush’s corner in November.

Kane’s latest poll for the Sun-Sentinel in late July showed a statistical dead heat between Gore and Bush in Florida if Graham was the Democratic vice presidential nominee. Without Graham, the vice president was running 6 percent points behind Bush.

In the end Florida came down not to six percentage points, which would mean a margin of over 300,000, but instead to 537 votes. Would Bob Graham have made that difference? Would these poll readings have held up? Would Graham’s in-state favorable rating of 62%—highest of all statewide office holders, higher than either candidate George W Bush or then-governor Jeb Bush—have spared us the Florida recounts, Bush v. Gore, and all that followed?

I prefer not to think about what might have been. I prefer to think instead about the remarkable example this man set.

Bob Graham, on the right, as governor, working as part of a volunteer trash-pickup crew in a drained lake bed.

As a longtime admirer and friend of David Allen, of Getting Things Done fame, I also respected Graham’s insistence that people never really believed that you’d follow through on an obligation unless they saw you write it down. David Allen has always emphasized the same point.

From the WaPo article:

The campaign seems to have tired of the [notebook] accounts, which some observers said portrayed the lawmaker as a little eccentric. Yesterday, his campaign seemed miffed that yet another journalist was writing yet another notebook story.

"I don't understand how this is a story," said spokesman Jamal Simmons. "You want me to comment on something that I don't want to comment on."

But why can't we see the notebooks?

“The American public is focused on its national security, its economic security, its health and social security -- and that's what this campaign is focused on," Simmons said.

Twenty years later, who seems more serious and sensible in this exchange: the reporter, or the politician (and spokesman)?

The official Senate register of the vote on invading Iraq is here. Among those voting No who are still in office: Debbie Stabenow, Dick Durbin, Patty Murray, Jack Reed, and Ron Wyden. Bernie Sanders was then in the House and voted No.

Graham was unusual within the anti-war block in his emphasis on “blowback”—that an attack on Saddam Hussein might trigger more terrorist attacks within the US. But like the others he said that case for war was much weaker than the administration claimed, and the risk of quagmire and disaster was much greater.

This was Gore’s remarkable address at the Commonwealth Club, in California. A sample:

We have other enemies, but we should focus first and foremost as our top priority on winning the war against terrorism.

Nevertheless, President Bush is telling us that America's most urgent requirement of the moment right now is not to redouble our efforts against Al Qaida, not to stabilize the nation of Afghanistan after driving his host government from power, even as Al Qaida members slip back across the border to set up in Afghanistan again.

Rather, he is telling us that our most urgent task right now is to shift our focus and concentrate on immediately launching a new war against Saddam Hussein. And the president is proclaiming a new uniquely American right to preemptively attack whomsoever he may deem represents a potential future threat.

If you’re wondering: Bob Graham was 63 at the time. Dick Cheney was 59; GW Bush was 54; Al Gore was 52. Gore’s eventual choice, Joe Lieberman, was 58. All obviously quite youthful by today’s standards.

I had forgotten that Graham was on the short list for VP in 2000. The might-have-beens in this case do not detract from your larger thesis about him, but add poignancy to his legacy.

James, I’m 70 years old. As a politically-aware junior high school and high school student, I lived through the assassinations of the 1960s. I also lived through the quagmire of the Vietnam War, and all the historic upheavals that followed.

In my mind, however, the greatest – and most devastating – “hinge of history” I have lived through was the George Bush versus Al Gore election. Our world would be so much better off today if Vice President Gore had become president of the United States.

Like you, it almost breaks my heart to think what may have happened if Bob Graham had been on the ticket as the vice presidential candidate instead of Joe Lieberman. He was far better prepared, and I think, a better man for the job than Senator Lieberman.

Thanks for this column giving Florida’s beloved Bob Graham his due. He deserved every praiseworthy word you wrote.