Election Countdown, 169 Days to Go: ‘Old Ghosts in New Garments.’

A striking phrase from Joe Biden's speech at Morehouse yesterday, which was another example of his underappreciated craft.

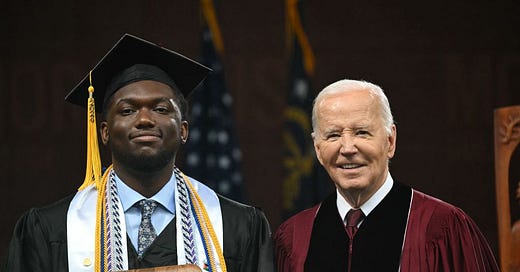

Voices of America, born in different centuries, together at Morehouse College in Atlanta yesterday. At right, commencement speaker Joe Biden, born the year after the attack at Pearl Harbor. At left, valedictorian DeAngelo Jeremiah Fletcher, born after the 9/11 attacks. (Photo Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images.)

Joe Biden may not be renowned as an orator. His lifelong stutter is one factor. I discussed some other reasons here, including the reality that he is most effective as a messenger when his language calls least attention to itself. But time and again, when the stakes are high, he has come through on big speeches as president. He has done so again.

His State of the Union address two months ago, soon after Robert Hur’s Comey-esque “elderly man with poor memory” pot-shot, was clear in writing and strong in delivery. His four-speech series of addresses on the fundamentals of democracy has been as good an example of sustained discussion of a single topic as we have seen from a modern president.

His commencement address yesterday to the graduating class of “Morehouse Men”—students at the all-male HBCU Morehouse College in Atlanta, brother institution to all-female Spelman College—was another example that deserves study. It showed care in craftsmanship and construction. Its phrasing matched Biden’s own style and diction. It navigated the political difficulties of the moment. And it represented Biden’s attempt to place those difficulties in a larger perspective. (The “as delivered” White House transcript is here; a YouTube video from the White House is here.)

Like nearly all commencement speeches, this one was longer—27 minutes—than a warm-day crowd might have wished. The golden rule for commencement speakers is: The shorter, the better, with haiku as the ideal. But everyone cuts sitting presidents extra slack. Their appearances in commencement ceremonies are rarer than you might think. By tradition, a president speaks once each year at a service-academy graduation—the academies take turns on a four-year cycle. But beyond that, a president typically makes only one or two additional commencement addresses per year.1 So when a university gets a president to speak, he is expected to offer more than mere bromides, and no one objects if he runs long.

The most interesting structural aspect of Biden’s address was its Saturday theme. Nine years ago, Barack Obama gave what I consider the most accomplished address of his public life. This was his “Amazing Grace” speech at the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in remembrance of the many parishioners shot to death there by a young white racist. Obama is remembered for bravely and unexpectedly ending that speech by singing the Amazing Grace song. He built up to that riveting moment with preacher-like but non-preachy recurring references to grace.

Biden’s hold on an audience will never be like Obama’s. But I admired the thread of Saturday that stitched together the parts of his political, personal, and spiritual appeal.

Saturday? Biden used it in an ecclesiastical sense that I hazily remember from Sunday School but that perfectly fit his message and seemed fully natural from him. This was not the “Saturday” of the afternoon college-football game and the evening kegger. It was the New Testament “Holy Saturday” between the Friday when Jesus was taken to the cross, and the Sunday when he stepped from the tomb. It was the metaphorical moment of unknowingness and despair. As Biden put it [emphasis added in all passages below]:

This graduation day is a day for generations, a day of joy, a day earned, not given. [The “earned not given” aside as an important validating and respectful touch.]

We gather on this Sunday morning because — if we were in church, perhaps there would be this reflection. There would be a reflection about resurrection and redemption. Remember, Jesus was buried on Friday. And it was Sunday, [Easter] Sunday that he rose again.

But we don’t talk enough about Saturday. When his disciples felt all hope was lost.

In our lives and the lives of the nation, we have those Saturdays. To bear witness the day before glory, seeing people’s pain and not looking away.But what work is done on Saturday, to move pain to purpose? How can faith get a man, get a nation, through what was to come?

The rest of Biden’s speech was about the “work done on Saturday”—when faith is tried, when hope seems dead, when the future is dark, when there’s no guarantee. He ended this way:

Class of 2024: Four years ago, it probably felt like Saturday. [With high school graduations cancelled because of Covid.] Four years later, you made it to Sunday—to commencement, to the beginning. [Combining the educational and the Christian-spiritual implications of a new start.] And with faith and determination, you can push the sun above the horizon once more. You can reveal a light and hope, I’m not kidding, for yourself and for your nation.

“The prayers of a righteous man availeth much.” A righteous man. A good man. A Morehouse man.

God bless you all. We’re expecting a lot from you.

And in between were passages like this, about the seemingly unending “Saturday” of the country’s reckoning with racial bigotry:

But let’s be clear what happens to you and your family when old ghosts in new garments seize power. [This is a very powerful phrase, which Biden has used at least once before. Both “ghosts” and “garments” are exactly the right words.] When extremists come for the freedoms you thought belonged to you and everyone.

Today in Georgia, they won’t allow water to be available to you while you wait in line to vote in an election. What in the hell is that all about? (Applause.) I’m serious. Think about it. And then the constant attacks on Black election workers who count your vote. [One of the speech’s leitmotifs is the Black patriots who love and work for the nation, which does not love and protect them in return.]

Insurrectionists who storm the Capitol with Confederate flags are called “patriots” by some. Not in my house. (Applause.) Black police officers, Black veterans protecting the Capitol were called another word, as you’ll recall.

They also say out loud [the “out loud” part being new in the Trump era], these other groups, immigrants “poison the blood” of our country, like the Grand Wizard and fascists said in the past. But you know and I know we all bleed the same color [after previous reference to Black military service]. In America, we’re all created equal. (Applause.).

The theme was familiar—“always darkest before the dawn”—and is familiar precisely because this is the note leaders are supposed to strike when things are tough. But in recent political rhetoric I don’t recall “it’s Saturday” being used as the connecting thread in quite so thought-out a way.

A major test of a speech’s success is whether the crowd seems more engaged at the beginning or the end. I wasn’t there, but from the videos it looked and sounded as if Biden had the crowd more and more with him as he went on. You can contrast this with recent Trump rallies, where the crowd kept thinning the longer he went on.

Placing ourselves in the river of time.

Nicolas Poussin’s famous A Dance to the Music of Time, from the mid-1600s. This painting was also used as the cover art for Anthony Powell’s renowned mid-1900s series of novels of the same name. (Wallace Collection, via Getty Images.)

The speech did something else, implicitly, that highlighted an aspect of leadership. It gave his listeners context. It placed them in the river of time.