Election Countdown, 157 Days to Go: Why Juries Matter

And how the rhetoric of 'Love It or Leave It' has reversed.

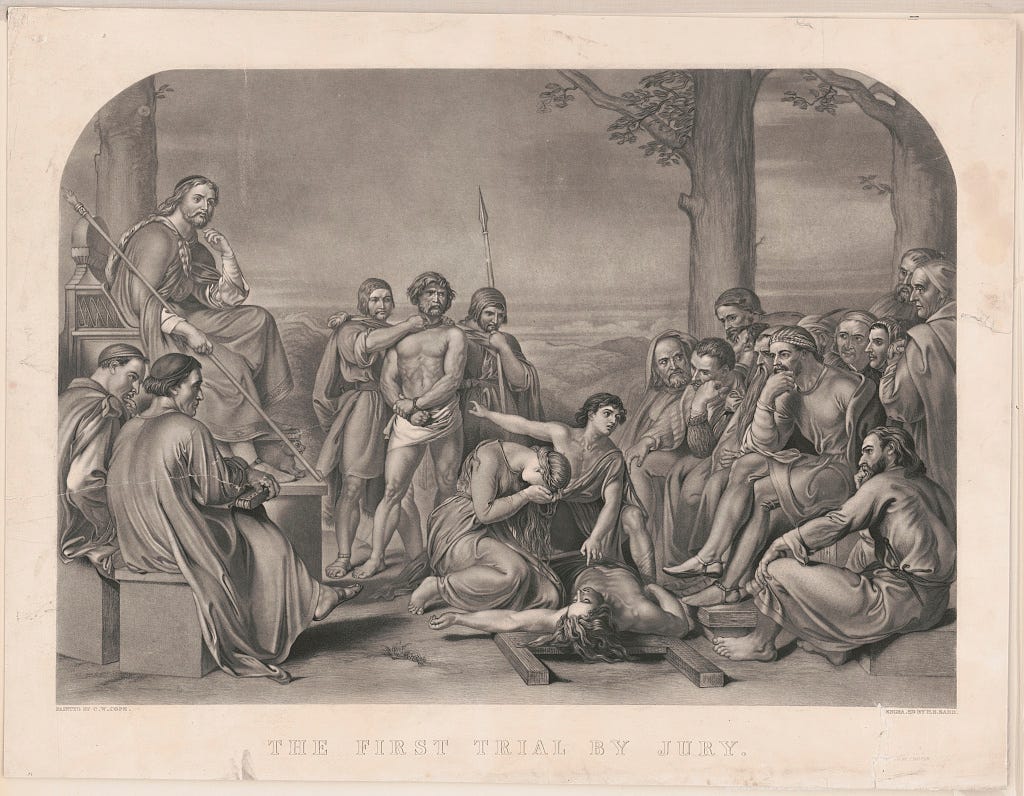

The First Trial by Jury, painted by C.W. Cope and engraved by H.S. Sadd, circa 1850. The defendant in this imagined scene is in custody, at center; the victim is lying dead in the foreground, being wept over; the judge is seated at upper left, holding a staff; and the jury is deliberating on the right. They wasted no time in those days. (Library of Congress.)

This post is about civic rituals, and civic love, in the aftermath of a jury’s 34 guilty verdicts against Donald Trump in New York this week. I will have two main points.

The first is that jury service deserves more attention, support, admiration, and willing participation than it usually receives. It deserves these things because it is the most important cross-class, cross-partisan, public-minded, genuinely deliberative experience that most of today’s Americans are ever likely to undergo.

It follows that anyone attacking juries or jurors is doing particularly noxious civic harm. (Even though juries make mistakes.) I’m talking about you, GOP.

The other is that the greatest US patriots are those who adhere to the American ideal, and strive for American possibility, even when American realities slap them in the face. “I, too, sing America,” wrote Langston Hughes when he was 24 years old and working as a hotel waiter in segregated Washington DC.

Nearly 30 years later, when he was called to testify before Sen. Joe McCarthy’s red-baiting investigative committee and grilled on his beliefs by the odious Roy Cohn—then McCarthy’s hatchet-man, later an ally of Donald Trump—this same Langston Hughes said: “I love the country I have grown up with. I am concerned with helping to build America, when sometimes I cannot even get into a school, or a lecture, or a concert, or go to a library and get a book out.”

These are the people who built our country and actually made it great.1 In our times Donald Trump has somehow managed to make an entire political party anti-hope, anti-idealistic, anti-institutional, anti-American.

Above, the 24-year-old Langston Hughes, working as a busboy at the Wardman-Park hotel in segregated 1920s Washington DC. He attracted attention when the then-celebrated poet Vachel Lindsay was staying at the hotel and “discovered” him. Below, Hughes in his early 50s, called to answer questions in Washington from Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn. (Getty Images.)

The rituals of our collective life.

First, I’ll talk about three major government-established rituals of civic life.

—At one extreme is military service. It is extreme both in the sacrifices it can demand, and in its comparative rarity now. After World War II, the combination of a large standing military, and small post-Depression birth cohorts, meant that most American families had first-hand connections to military service—and in many cases, to combat experience as well.

Now only a relative handful do. As I wrote in “Chickenhawk Nation” nine years ago, a total of 2.5 million American served in the US military in Iraq, Afghanistan, or their surroundings through the first decade-plus of the “long wars” there. That was about 3/4th of one percent of the US population. The active-duty military now numbers about 1.3 million Americans, or well under half of one percent. Through the millennia, military service has bonded those who have been through it, “we band of brothers”-style. It still creates that bond and identity, but among a relative handful.

—At the other extreme is voting. Nearly 160 million Americans, some two-thirds of the eligible population, cast a vote for president in 2020. That was the highest turnout rate in more than a century. Over the past decade turnout rates have been going up. On election day most of us feel a ritual bond in joining a public event whose outcome we can’t be sure of until it happens—and may lament once it has occurred.

This year, once again, get out the vote!

—In between is the underappreciated civic ritual of jury service.2 When the topic is discussed, it’s usually as a chore to be avoided—“Oh no, what excuse can I give this time?”—or as another chessboard on which legal strategists and schemers can operate. Jury-curating is the running theme of the CBS series Bull and of countless courtroom novels.

But jury service is apparently a more widespread experience than I had thought. Numbers are tricky, given all the different levels of American courts. But a 2012 survey found that 27% of adult Americans had actually served on trial juries at least once in their lives. A study last year concluded that 11 million Americans report each year for jury service, and that about 1.5 million ended up sitting as jury members at trials.

I wish even more people would have this experience. It makes being a citizen vivid and tangible in a way that’s hard to match in peacetime life.3

What you learn on a jury.

I have been on three trial juries that deliberated their way to a verdict. All have been in Washington DC. (In some jurisdictions, you’re excluded for being a lawyer, or a journalist, or a government employee or law-enforcement staffer. In DC, they need everyone to serve, and they wave you right in.) Two were “normal” drug-dealing cases. One was a shooting. Two were resolved after a few hours of deliberation. One took several days.

All of the juries were “diverse” in ways more fundamental than the formulaic use of the term. As I remember it, all of them were 7-5 female over male. All were “majority-minority,” with Black and Hispanic jurors making up seven or eight members of the group. All had members in their 20s, and members in their 70s. Professional people (lawyers, doctors, NIH researchers, State Department officials); hourly workers (truck drivers, cab drivers, food-truck operators); and the unemployed. People with multiple advanced degrees, and people who had not finished high school. One woman who needed an oxygen tank to get through the day’s discussions. The range of our country.

And in all these cases, all 12 of us actually discussed and deliberated over the evidence. People as they come across in “guy in a diner” stories do not sound smart. People in a jury room—in my experience—sound as if they are paying attention. And when you know that you finally must come to a unanimous decision, you listen, and think, and do so.

In one of the cases, I changed my mind through the course of deliberation. In other cases, I think the process changed other people’s minds. In all of the cases, the 12 of us walked out at the end and gave our verdict to the judge.

I have never seen any of these people again, but we were a unit at the time.

What am I getting at here? Anybody who goes on TV or issues statements saying that this latest case was a “rigged trial” or a “New York jury” can go straight to Hell. And anyone who tries to doxx or torment these people, including the alternates, deserves the express lane downward. I hope and assume that protections are lined up for the jurors and the judge. (And respect, by the way, to the neighbors and work colleagues of these jurors who must have figured out who they were, but who have kept that info to themselves.)

These people have done their civic duty. They would not have taken it lightly. I hope none of them is made to regret this service.

Believing in America

The more I live through our country’s travails, the more I respect the Black American patriots who over the centuries have loved the country even when it did not love them back.