Does Politics Turn on a Message? Or a Messenger?

And other ramifications of Jimmy Carter's 100-plus years. Which may give the Democrats a challenge different from the one most often discussed.

With boots facing backwards, a riderless horse as part of Jimmy Carter’s state funeral observations in an Arctic-seeming Washington DC this week. (Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images.)

This is a “back on the grid” post, after an unexpected past month in which I was doing many things outside computer range and very little online.

Through much of December, Deb and I were out of the country and away from online connections. First that meant Panama, as described here, about which I’ll write more. And then Italy, with family.

As soon as we returned to DC, we were immersed in events following the death of Jimmy Carter. (A list of some of the TV and radio/podcast presentations that have mainly occupied me in the past week-plus, below1.) Meanwhile we have been digging and re-digging our house in DC out of the continuing ice and snow. Thanks to everyone who has stuck with me through this unusual period!

This post has three main themes. The first one is longer than the other two. They are:

A distillation of what these past 12 days of remembering Jimmy Carter have revealed to me about his time, and ours.

A link to some useful starter discussions about what could and should come next, on the policy front.

An evolving thought about what comes next in politics. This is something that became clear to me only when I said it out loud in a broadcast. It’s a perspective that that makes the Democrats’ challenge a little different from what’s generally discussed, and even more complicated.

Here we go:

1) What we’ve learned about James Earl Carter Jr.

Since the beginning of this year I’ve spent most waking hours reading about, hearing about, or talking about Jimmy Carter. The through-lines that stay with me are:

For most of today’s Americans, the most difficult thing to imagine about Jimmy Carter is how young, vital, exciting, and transformative he seemed when coming from nowhere to the presidency back in 1976.

Most people alive today know Jimmy Carter only as a kindly, geriatric, post-politics figure. But the electorate that chose him just after the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandals thought of him as exciting, fresh, energetic, new. That is what I discussed in this CBS Sunday Morning eulogy of him, and at more length in podcast discussions this week with John Heilemann and with James Carville and Al Hunt. Remember, Carter still holds the record for first-term positive approval ratings—over Barack Obama, Ronald Reagan, and any other modern president (except GW Bush in the immediate national-unity aftermath of the 9/11 attacks). Carter’s rapid fall from that peak of approval is the familiar part of his story. His preceding rise, now mainly forgotten, was extraordinary.I’ve been reminded that through his very long lifetime, Jimmy Carter was the same person, for better (most of the time) and also occasionally for worse. The “for better” part involved the elements that Joe Biden stressed in his remarks two days ago at the National Cathedral. Integrity. Honesty. Faith. Character. The “for worse” part was his determination to do things exactly his own way—which was brilliantly successful during his decades of international work through the Carter Center, but which led to some logjams when he was in Washington. During his nearly 44 years out of office, he could play to all his strengths and do things just the way he chose. During his four years as president, he had to deal with the Congress, the DC press, lobbyists, the public, and so on.

Journalists, historians, and politicos talk constantly about the role of character, policy, politics, and world-framing events in shaping election outcomes.

In thinking about Jimmy Carter, I’m more and more taken by the role of sheer luck. That was the theme of a pre-obit I wrote nearly two years ago when Carter went into hospice. (Original Atlantic version here. Non-paywalled Substack version here.)

The ways in which luck broke against Carter in his time in office, especially the final two years, are well known. But in my talk with John Heilemann I emphasized a bit of positive luck whose importance has, for me, steadily grown over the years:

In 1974, the then-world-famous “gonzo” reporter Hunter S. Thompson, happened to be following Senator Edward Kennedy to Georgia for a speech, where he happened to stay an extra day and instead was awestruck by a speech from the first-term governor of Georgia. (You can read the speech here.) Thompson became one of Jimmy Carter’s most fervent advocates. This was a crucial, even irreplaceable part of Carter’s becoming “cool.”

More and more I believe that if Thompson had not been there to follow Kennedy, had not stayed an extra day, and had not gone on to declare Carter’s remarks a “king hell bastard of a speech,” Jimmy Carter would never have gotten traction in the Democratic primaries nor ended up in the White House. (Modern comparison: people talking about how Joe Rogan sealed the deal this time for Donald Trump.) Here is how the historian Sean Wilentz recently put it, also in Rolling Stone:

“Out in the audience, the gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson could scarcely believe his ears. Thompson was covering Sen. Edward M. Kennedy’s own incipient presidential campaign for Rolling Stone; the senator had addressed the Law Day assembly the day before and remained for the rest of the proceedings, so Thompson did too.

“ ‘What the hell did I just hear?’ he asked a Kennedy aide, who, smirking, replied that Gov. Carter had just announced that ‘his two top advisers are Bob Dylan and Reinhold Niebuhr.’

”That did it: Thompson leapt to his feet, ran to his car to retrieve a tape recorder, and captured the rest of what he would later call Carter’s “king hell bastard of a speech.” Thompson then decided to write a Rolling Stone cover profile of Carter that helped establish the governor as a serious contender for the White House.”

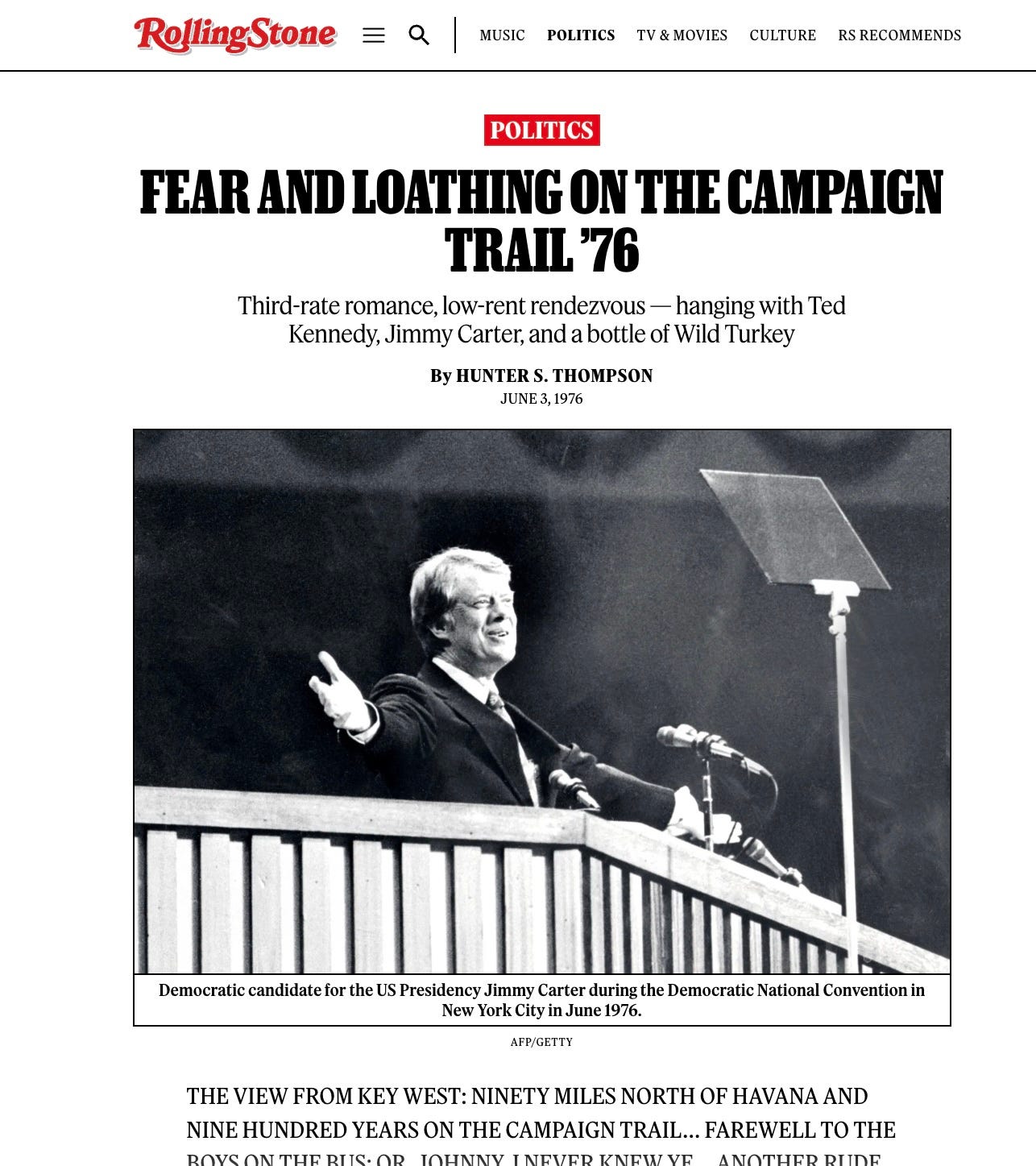

Character. Preparation. Policy. Those things matter. So does luck. (Below, one of HST’s articles about Carter later in that 1976 campaign.)In the tributes at the Capitol and at the National Cathedral, everyone from Stuart Eizenstat (longtime close Carter aide) to Kamala Harris to Joe Biden emphasized things Carter did as president that will last. Energy policy. Environmental protection. The Camp David accords and Panama Canal treaties, and more. On reflection I’ve been reminded of one that deserves more attention than it usually gets. That is Carter’s emphasis on human rights as a factor (not an absolute) in US foreign policy.

During my discussion two days ago with Christiane Amanpour, she quoted several lines from Carter’s most important speech on this topic—his commencement address at Notre Dame, in 1977. That’s a speech I was involved in. Fortunately—and atypically, while on live TV—I recalled the lines that came immediately after the ones she had quoted.2 I think the whole passage is worth noting here, in reflecting on Carter’s outlook on the world.

“We have reaffirmed America's commitment to human rights as a fundamental tenet of our foreign policy….

“This does not mean that we can conduct our foreign policy by rigid moral maxims. We live in a world that is imperfect and which will always be imperfect--a world that is complex and confused and which will always be complex and confused.“I understand fully the limits of moral suasion. We have no illusion that changes will come easily or soon. But I also believe that it is a mistake to undervalue the power of words and of the ideas that words embody. In our own history, that power has ranged from Thomas Paine's "Common Sense" to Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream."

“In the life of the human spirit, words are action.”

It’s the kind of idealistic-but-practical moral calculus that Carter would have linked to Reinhold Niebuhr, and that got attention from Hunter S. Thompson three years earlier. If you’d like more on Carter’s moral-but-practical vision, please make time to read this superb new article on Carter’s admiration for the classic book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by my longtime friend Lincoln Caplan.All of the remarks at the Cathedral were powerful. The three that stood out to me were:

Steven Ford, reading the eulogy that his father, the late Gerald Ford, had written for his one-time bitter political adversary (and later close friend) Jimmy Carter; Jason Carter, with his jokey and realistic loving appraisal of his grandfather and grandmother; and Joe Biden, who paused for emphasis on all of the positive character traits that distinguished Jimmy Carter. It seemed to me that Biden was looking directly at Donald Trump when he said these words:

“We have an obligation to give hate no safe harbor, and to stand up to what my dad used to say is the greatest sin of all, the abuse of power.”

2) Thinking about policy.

What is to become of the Democrats? How can they walk the walk, and talk the talk, about re-expanding their base?

That’s an enormous topic, for the days and months ahead. As a start I’ll offer one link.

My original home in the magazine world, The Washington Monthly, has a new issue on exactly this topic. You can read the whole thing online here and here. (I subscribe to the magazine, and hope you will.) Its title is a guide: “Ten New Ideas for the Democratic Party to Help the Working Class, and Itself.”

It includes ideas for health care (essentially, expanding Medicare’s price-bargaining power, to offset gouging by the health insurance-industrial complex); empowering small businesses and entrepreneurs (and protecting them against vulture-capitalists); making higher education broadly affordable again (a new grand bargain connecting community colleges with four-year institutions); plus lots more. I don’t agree with every detail in this manifesto, but it’s a valuable step in the “What is to be done?” direction. More on TWM’s proposals, and others that are already appearing, in upcoming reports.3

3) Thinking beyond policy.

Here is the idea that came to me only as I was saying it, at the end of the discussion with John Heilemann.

Heilemann asked me, What is to be done on policy? And I told him I didn’t know.

And then I said something like: The hard truth is, maybe that’s not what will make a difference for the Democrats.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Breaking the News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.