Are Autopilots Dangerous?

Yes. No. And it depends. What to know during the holiday travel surge, when you're on the road or in the air.

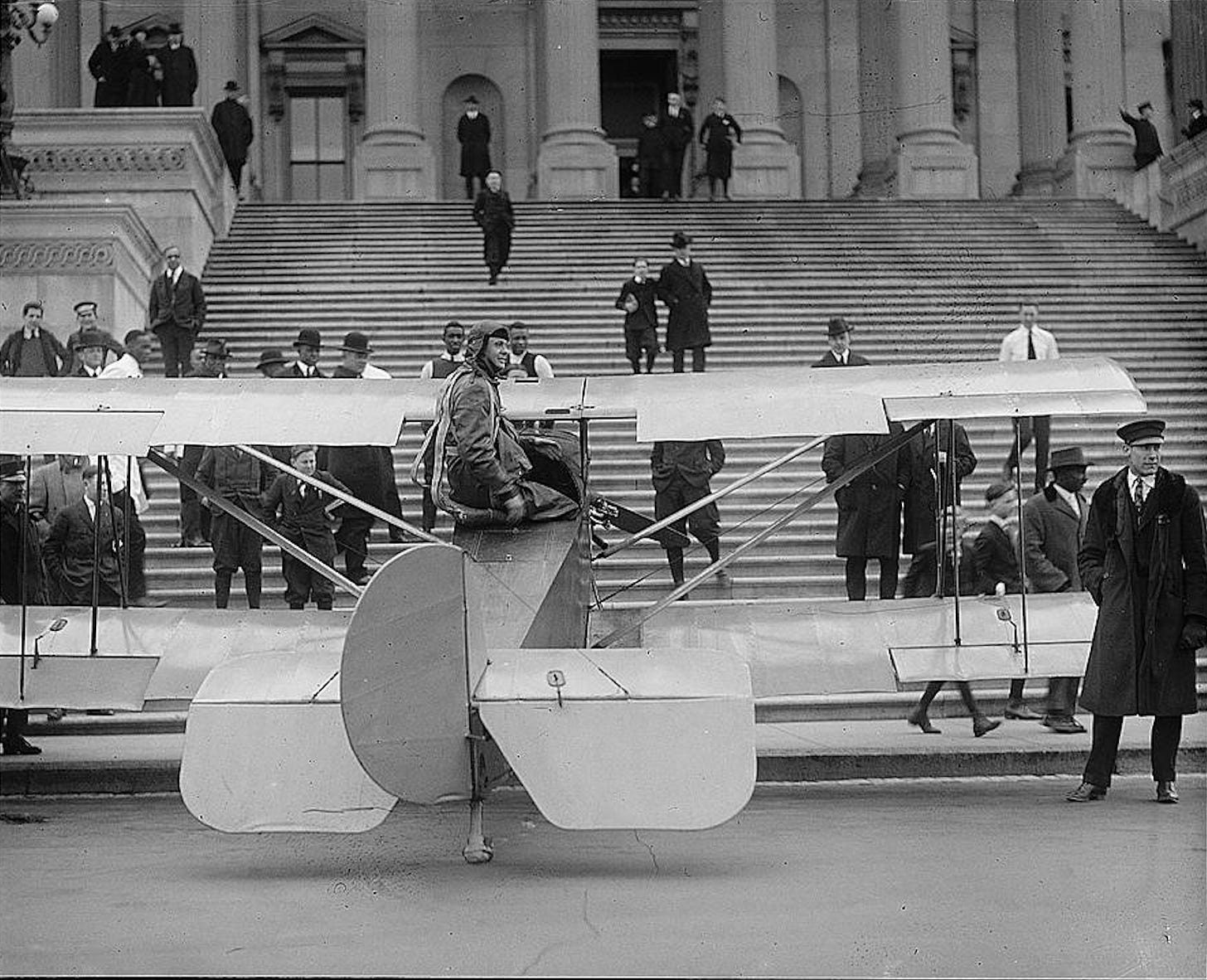

Lawrence Sperry, inventor of the first airplane autopilot, just after landing his tiny “Sperry Flivver” airplane on the east plaza of the US Capitol complex in 1922. The plane took longer to slow down than he expected, so as a braking technique Sperry steered it up onto the steps to the Senate chamber. (Library of Congress.)

The news pegs for this post are the recall order last week for 2 million Tesla cars; the FAA and NTSB announcements this week about stresses on pilots and controllers in the commercial air-travel system; and the flood of holiday-season travel that ramps up today and is expected to pass pre-pandemic levels in the coming week.

My connecting theme will be the role of autopilots. The summary is:

-Today’s car autopilots make things riskier for people on the ground;

-Modern airplane autopilots make things safer for people traveling by air;

-And the outlier cases where autopilots have added to aviation risk highlight their hazards in use on the roads.

To take these in order:

1) ‘Self-driving’ cars’: No, thanks.

Six months ago, Deb and I bought a new Tesla Model Y, as recounted here. Overall it has been great. No reliability, workmanship, or on-the-road issues. Every time I drive the other car in our household—a still-beloved 23-year-old Audi A4—I realize how much I’ve come to rely on the Tesla’s “situational awareness” features, and how different it feels to know that we won’t ever need to stop for a tankful of gas.1

But this car, like millions of others, was part of the past week’s mass “recall” of Teslas, because of dangers with the auto-steer and autopilot systems. I put “recall” in quotes because, as I understand it, mostly the adjustments will arrive as cloud-based software updates, of the kind Teslas routinely get every few weeks.

Our Tesla came with built-in auto-steer and other automated guidance and braking capabilities. We did not sign up for extra, purportedly “full self-driving” systems. And I’ve barely ever used the even assistive systems that came standard with the car.

Why? The minor reason is that I simply like having a sense of direct control. The Audi has five-on-the-floor manual transmission. Having grown up with stick shifts, that’s the way I prefer to drive.2

The more rational reason is that nearly all of our driving has been in-town short-hauls, not the long freeway stretches optimized for car autopilots. Statistics will no doubt show that in carefully controlled circumstances, like an Interstate, automated systems can be safer than fallible human drivers. After all, the robot-drivers will not be on their phones, or drunk, or falling asleep, or venting road rage. And if people in each vehicle knew that all the other vehicles were also under automated control, then everyone could relax and let AI systems keep the cars safely separated. Airplanes can do something like that now.3

But that’s not how driving works, or will for the foreseeable future. The other cars on the road aren’t under AI guidance. Neither are the dogs, deer, pedestrians, squirrels, double-parked Amazon vans, stoplight-running SUVs, or other random hazards that appear out of nowhere and complicate real-world driving life. Computers are worst at dealing with the real-time unforeseen.

Everyone who has flown an airplane has a version of the following story: You land the plane—sometimes in bad weather, often with a crosswind, always after managing the 3-D challenge of guiding a craft from flying speed high in the sky to touchdown speed a few inches above the runway. You’re relieved.

Then you get in a car, turn onto the access road, and suddenly you realize: My God! People are coming at me head-on in the opposite direction! With not very much separation! A few inches’ misjudgment when landing can mean a bumpy touchdown. A few inches’ slip of the steering wheel can be a lot worse. “Hand-driving” a car in those circumstances is demanding. But leaving it to an autopilot is more risk than I am willing to take on.

Lawrence Sperry’s plane just after he steered it up the Capitol steps, with onlookers rushing over. (Library of Congress.)

2) ‘Airliners on autopilot’: Yes, please.

Modern airline disasters are so rare that nearly any of them can seem to constitute a trend. Thus the Air France Flight 447 disaster over the mid-Atlantic 12 years ago has been studied as a cautionary example of pilots being confused by an autopilot. And the United Airlines plunge toward (but not into) the Pacific on departure from Maui early this year also seems to have involved pilots mis-reading or mis-handling their cockpit automation.

But overwhelmingly, these two things are true about modern airline travel:

—The human pilots are extensively trained and tremendously skilled.

—Part of their skill is knowing when to rely on automation.