An Early Casualty in the AI Wars

The startup search company Neeva promised users an ad-free search experience. It delivered, but then circumstances changed. A tale from the AI shakeout.

The founders of the startup search engine Neeva.com, which has just announced that it is ceasing operations. (Photo from Neeva site.)

I’ve been beavering away for a long post on—you guessed it!—politics and the press. It’s still making its way through my computer, and the subject is evergreen. More soon.

For now this is a quick follow up on something I wrote 18 months ago, which has taken an unexpected turn. Perhaps the story is just another reminder that startups are by definition risky. Perhaps it’s an indicator of upcoming developments in the tech world. We can’t know at the moment, but here’s what has occurred:

In a post back in 2021, I explained why I was changing my default web-search preference from Google, whose products I rely on in most other aspects of my digital life, to a new company called Neeva.

Neeva had a strong Google connection. One of its founders, Sridhar Ramaswamy, had been at Google for 15 years, including five years as Senior VP in charge of the company’s ad revenue. The other founder, Vivek Raghunathan, had been at Google nearly as long, and was in charge of monetization for YouTube.

Precisely because of what they had seen at Google—especially the “manifest destiny” to continue increasing ad revenue—the two men decided to build a different kind of search company. I talked with Ramaswamy and quoted him at length on his vision. I think his views are interesting to read in retrospect. In simplest terms they came down to the idea that the better Google search became as an ad-delivery mechanism, the worse it had become from the user’s point of view.

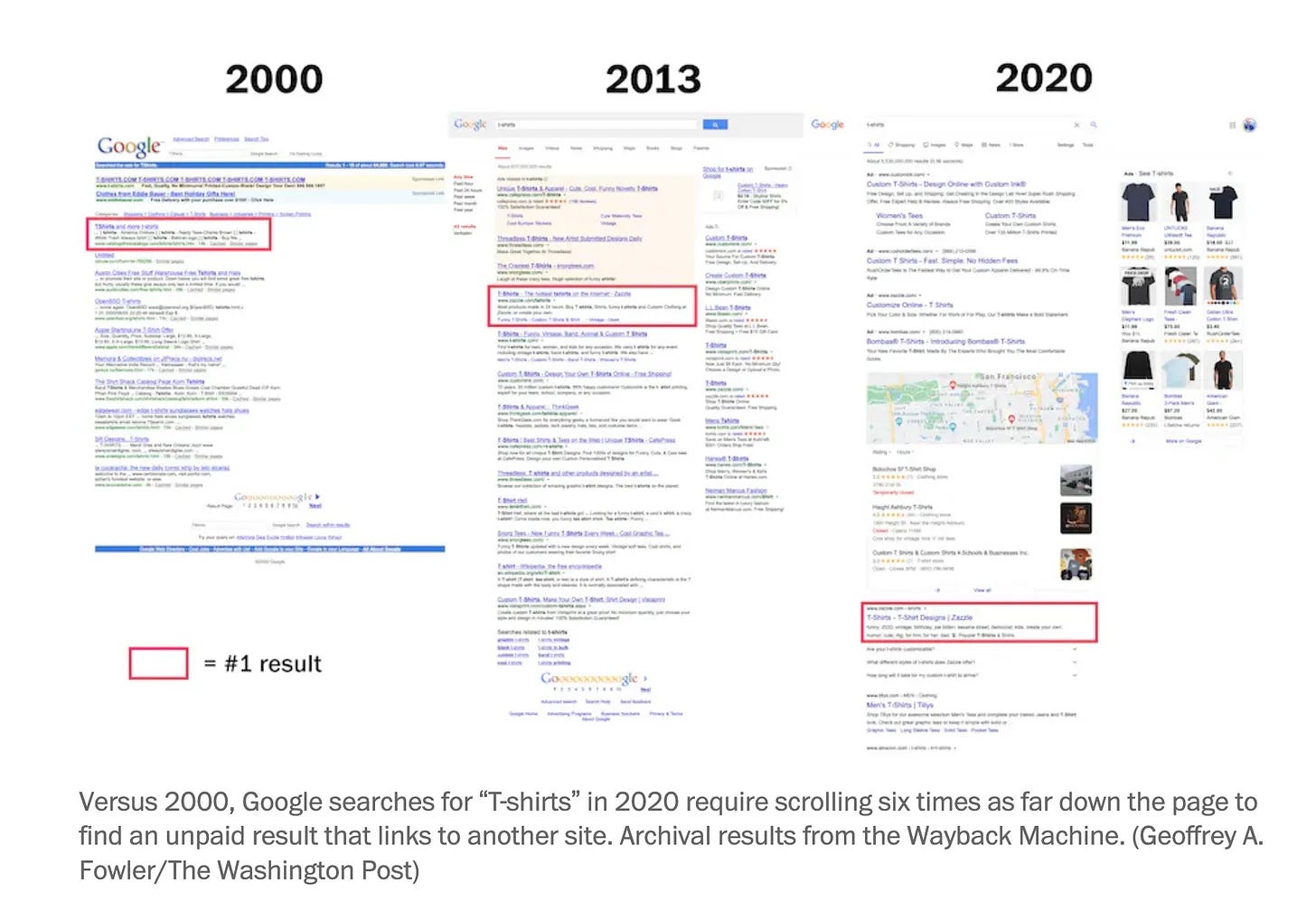

In that article I used one graphic by Geoffrey Fowler, of the Washington Post, to illustrate the problem. Fowler showed how over a 20-year span the Google results for the same search terms had changed. In 2000, 2013, and 2020 these were the results of a Google search for “T-shirts.” The red boxes show how far down you have to go to see a result that is not an ad.

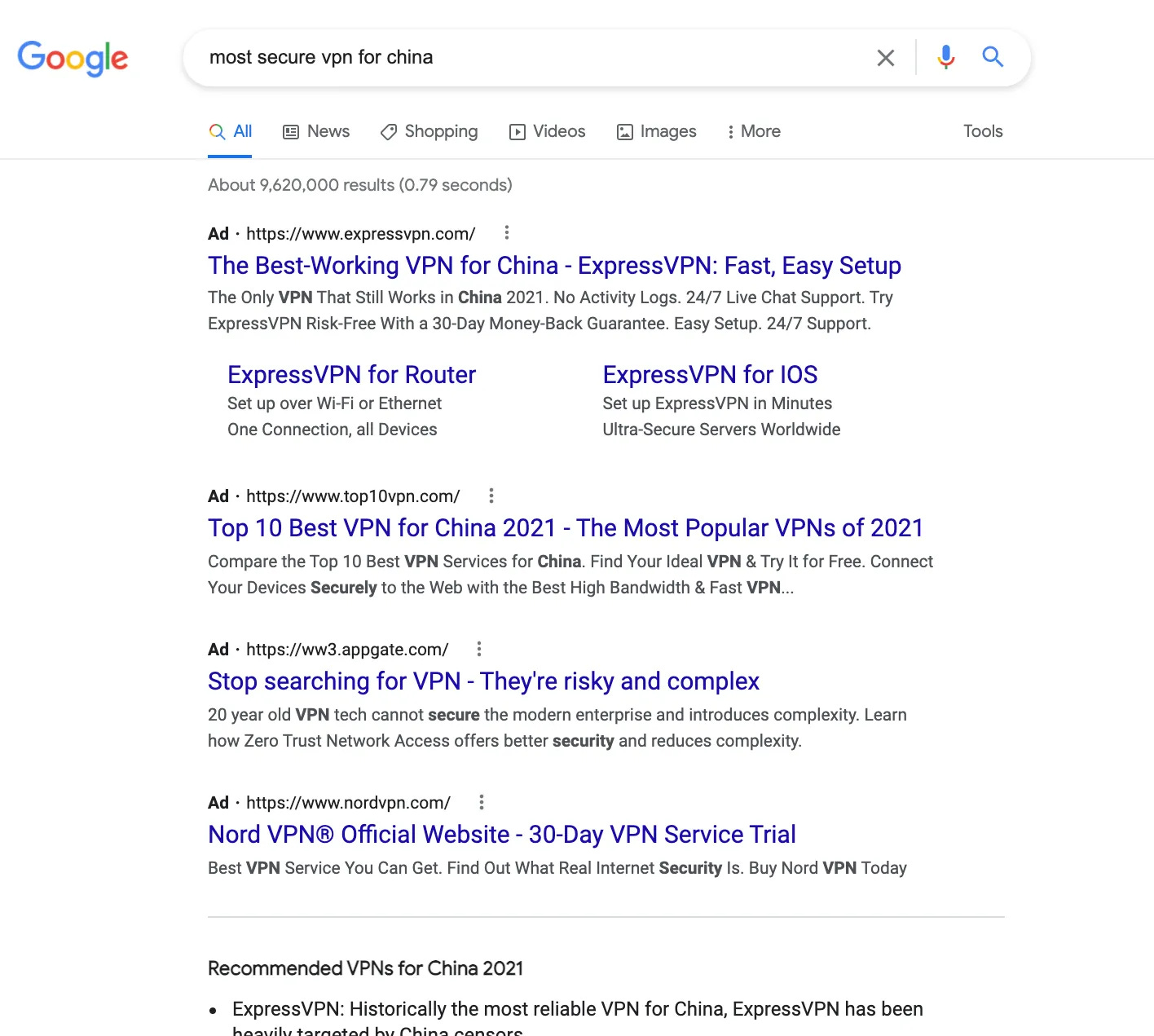

I was intrigued by Fowler’s article and ran a test for myself, searching for “most secure VPN for China.” The first screenful of Google results I got was entirely ads.

That was in 2021. I ran that same search on Google again just now. Same outcome: a first screen that is purely ads. Though now they are identified not as “Ad” but as “Sponsored.”

‘When it’s free, you’re the product’

Neeva’s proposition was: We’ll make our money from subscribers, not from advertisers. If you pay us a modest fee, we’ll take you straight to the results. It was the HBO or Netflix model, applied to search.

It sounded good to me. I had signed up for Neeva as an early beta tester. When it went on the market I became a paying subscriber. I have gratefully used it ever since. For nearly two years I’ve done every one of my countless web searches with Neeva. It has given me everything I was looking for, without the waxy carapace of ads.

That is why I was sorry, on many fronts, to see this banner on all Neeva sites over the weekend:

What happened, and why? The founders started giving an answer in their statement this weekend announcing the shutdown. Part of the story, they say, was the sudden impact of consumer-facing AI on the entire search industry. Neeva was actually faster than Google or Bing to make AI-generated answers part of its search results, as it did early this year. But obviously it could not compete with them on scale.

Ramaswamy and Raghunathan also emphasized that customer behavior—simple habits and inertia—may have been an even bigger part of the challenge. As they put it:

Throughout this journey, we’ve discovered that it is one thing to build a search engine, and an entirely different thing to convince regular users of the need to switch to a better choice.

From the unnecessary friction required to change default search settings, to the challenges in helping people understand the difference between a search engine and a browser, acquiring users has been really hard.

Contrary to popular belief, convincing users to pay for a better experience was actually a less difficult problem compared to getting them to try a new search engine in the first place.

Everything about industrial structure in our era involves understanding what consumer choice and effective competition really mean, under today’s technological and market conditions. “Lock-in,” scale barriers, “default settings,” and other factors deserve far more attention than they get in the standard economics text. The era of Apple, Google, Facebook has upended many business truisms. The advent of AI will no doubt do so too. We just don’t know how.

When the dust from Neeva has settled, I hope to speak to its founders again, for more detail on what their company’s saga means, and what they’ll do next. I wrote to Ramaswamy after the news broke and got a note from him this evening. It ended:

Startups, especially very ambitious startups, are always knife edge affairs. While I obviously regret that we were not the roaring consumer success that I hoped we would be, I am glad that we had the courage and the audacity to try.

Easy for me to say, but: I am glad as well. They have my gratitude and respect.

David Pierce of The Verge has a story on the Neeva shutdown, here.

And, speaking of lost eras in computing, here is a story I wrote in The Atlantic 41 years ago, about what the advent of personal computing might mean. Some of it now seems as if it was from a prehistoric age. Some of it could have been written last night.

My 21 year old grandson has been giving me a tutorial on AI. [As a kid I recall communicating with two tin cans and a string.]

What I found truly frightening was Ross Andersen’s article in The Atlantic in which he described, in excruciating detail, how AI could reduce the response time to a possible nuclear attack to nanoseconds. Also, because of counter cyber developments, how such a response might be left to machines and/or some person at a nuclear base or on a nuclear sub.

As a former professor my concern about student AI essays is of a lower timbre. In the pre-AI days I could sense student plagiarism (I maintained student portfolios). I would speak to the student and then ask him/her to pronounce and define a fancy word in the essay. BINGO!

What a blast to reread "Living With A Computer." I will never forget the single most exciting thing about first using a word processor (in 1985): footnotes. The program automatically fit notes on the pages, and when one added or deleted a footnote, all the subsequent notes were automatically renumbered!!