A New Search Engine Worth Trying: Neeva

Billions of people use Google search. Now it's billions minus me.

This post is about an online search system that I’ve used long enough to be comfortable recommending to others. More generally it’s about the worsening dystopia of the advertising-based “attention economy” of connected life, and what solutions and responses are starting to emerge.

If you want to skip to the conclusion, here is what I’m suggesting: Give Neeva.com a try.

If you’d like the backstory, let’s begin with what has happened with the global giant in online search, Google.

A company I have loved

I am a long-time fan of Google. I knew its founders and early leaders when the company was getting started. My wife, Deb, and I remain in touch with some as friends. One of our sons has worked there. I signed up for a Gmail account practically the minute the service went public. Last year I wrote about one of the creators of Google Earth, our dear friend Michael Jones, on the occasion of his untimely death. When I’m not checking views-from-above with Google Earth, I’m finding land-based routes with Google Maps.

A decade ago, Michael Jones and some Google security experts helped Deb after her Gmail account was hijacked remotely, as I recounted in an Atlantic article. Since then I have used and ceaselessly touted Google’s free “Advanced Protection Program” to ward off such attacks. When we lived in China, I was heartened by Google’s stand against Chinese censorship. I’ve admired and written about the free tech-training courses and tools offered by the company’s under-appreciated Grow With Google project. We even have Pixel/Android phones.

And so on. My life would be worse without these many tools.

But…

But in the past year or two, I’ve grown less and less fond of the feature that originally made Google, Google. Namely, its power and convenience in finding what I want on the web.

The power is still there. No one can match the speed or reach of Google’s indexes and algorithms. Just ask Baidu or Bing.

It’s the convenience that’s waning. Originally the Google search page was a minimalist-elegance vehicle for taking you straight to the desired results. Now it is too often a maximalist-clutter way to serve up ads, with the actual information seeming an afterthought or lagniappe. From the user’s point of view, the signal-to-noise ratio has gone way down.

Paging Dr. Kildare

To be precise about what I’m saying: You can still construct searches that lead to maximum signal, minimal noise. For instance, choose some medical term—let’s say, “subdural hematoma,” which I recall from a TV episode of Dr. Kildare when I was a kid. Not many people are trying to sell you a subdural hematoma home-care kit. So if you type those words in, you get “real” results:

For now, let’s skip the question of which results end up at the top of the list, and why. The point is, none of them is an ad.

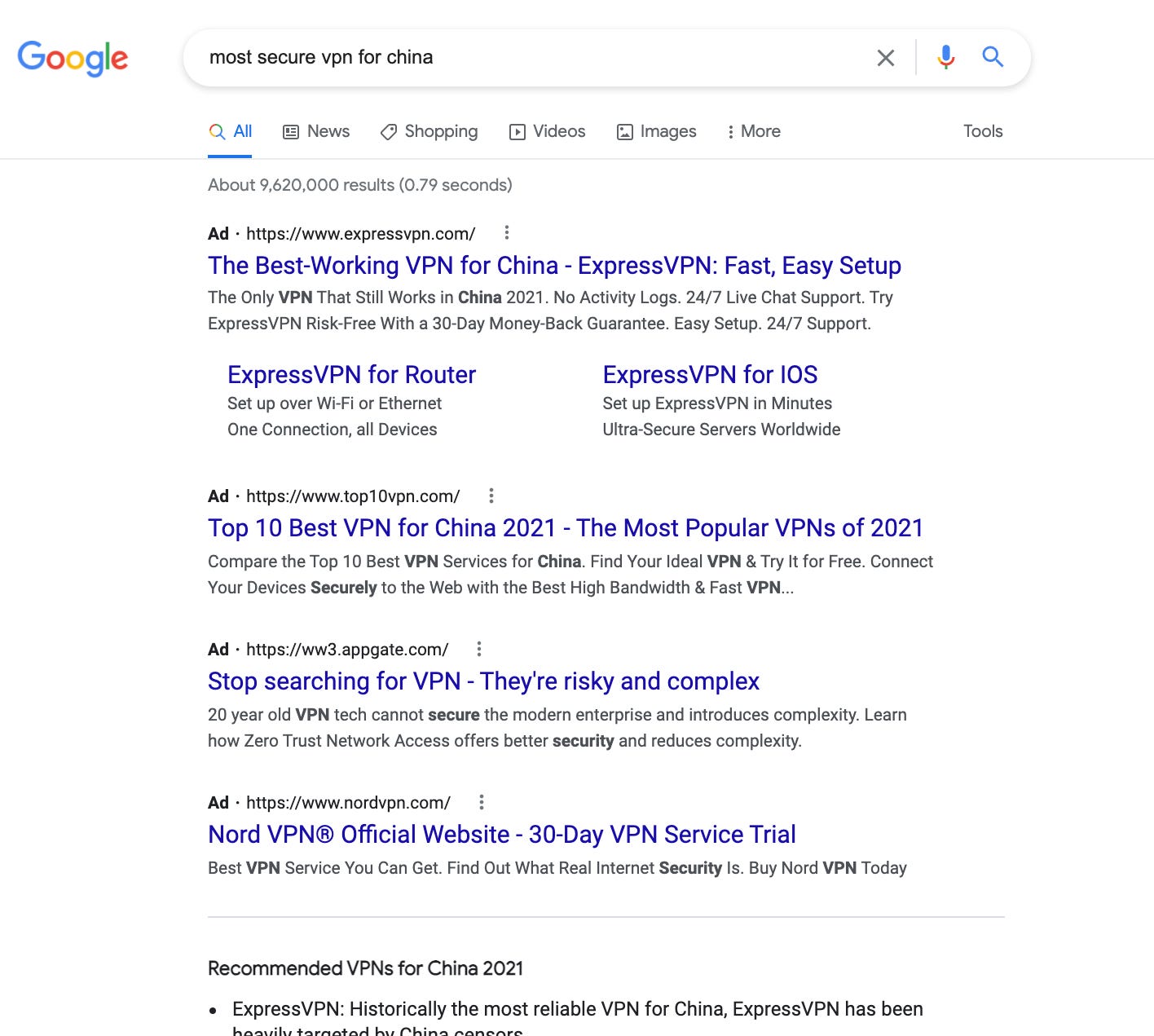

But as soon as you enter terms that might lead to a purchase, the signal-to-noise ratio switches. Suppose I was going back to China and wanted to check which VPNs currently work best at avoiding its Great Firewall. I enter “most secure VPN for China,” and I get a geyser of ads:

It was not always thus

Google’s revenue has always come from ads. So hasn’t it always been like this?

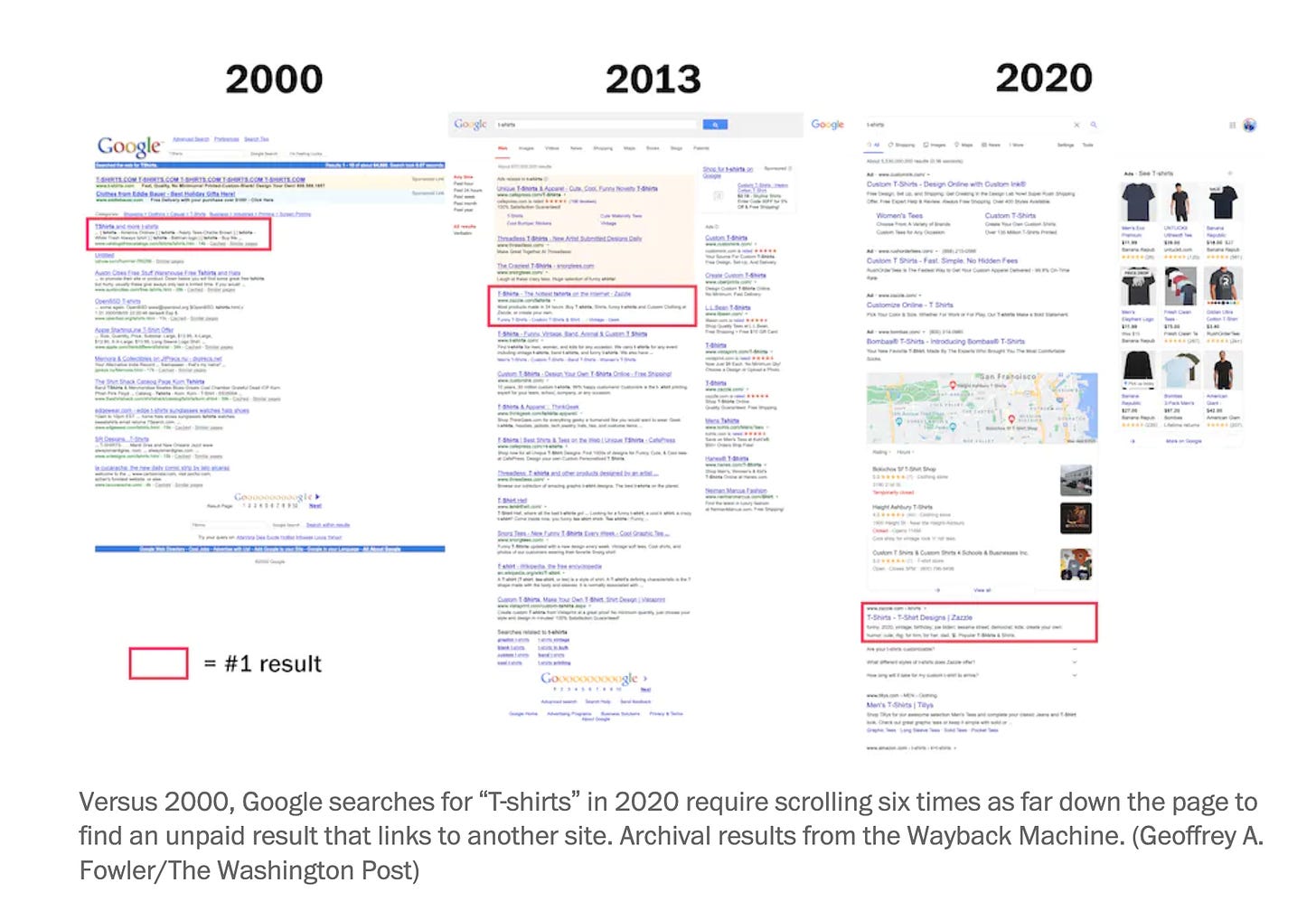

No, it has not. Geoffrey A. Fowler, of The Washington Post, demonstrated this in a column last year, whose informative subtitle was “Right under our noses, the Internet’s most-used website has been getting worse.” Fowler went to the indispensable web-archive “Wayback Machine” to compare the results from the same Google search run in 2000, 2013, and 2020.

You won’t be able to read the tiny type in the screenshot image from his piece, below. But the significance is the sequence of outlined red boxes. Those show the #1 “real” result, offering a link to a non-Google site, from a search for “T-shirts.”

As you see, in 2000, it was right near the top; in 2013, a little further down; in 2020, much further down, beneath ads of various sorts. Those ads, as well as being more numerous, are much less clearly marked than before. For instance, note the colored shading that signals “This is an ad!” in 2000 and 2013. It’s gone now.

Also note in 2020 the group of other results that come after the “normal” ads, but before the “real” results. They also are forms of advertising—“affiliate links,” “featured snippets,” and other presentations that keep you on Google’s page, and therefore exposed to its advertising, rather than connecting to someone else’s site (and giving that other site traffic and exposure).

Fowler’s article is full of similar illustrations and is very much worth reading.

Manifest Destiny, digital style

“The natural end point of an ad-based system is always and only to make more money,” Sridhar Ramaswamy told me. “Completely ad-supported products go off the rails slowly but surely: They keep adding more and more ads, making the user experience worse and worse, all in an effort to make more and more money.”

He would know. Sridhar Ramaswamy spent 15 years at Google, including five years, from 2013 to 2018, in overall charge of ad revenue, as Senior VP for Advertising and Commerce.

Ramaswamy described Google’s continued expansion as being guided by a kind of “manifest destiny” vision. It believes it can provide more and better information than anyone else. Therefore it is not simply in its own interest, but also a benefit for the world as a whole, that it become ever-more-completely the go-to source.

As Ramaswamy put it to me, Google “intrinsically operates with a belief system that says that it can do a better job answering a user’s query than anyone else can. Areas like image search, local, books, wikipedia were all absorbed into Google search. I call this the Manifest Destiny belief of Google: that only it can truly show you relevant information directly, without any intermediaries.”

I have heard versions of the idealistic part of this concept over the years, from many people at the company. Here’s the way it was set out in 2004, in the famed “Letter from the Founders” that accompanied Google’s IPO offering:

DON’T BE EVIL

Don’t be evil. We believe strongly that in the long term, we will be better served—as shareholders and in all other ways—by a company that does good things for the world even if we forgo some short term gains. This is an important aspect of our culture and is broadly shared within the company.

Google users trust our systems to help them with important decisions: medical, financial and many others. Our search results are the best we know how to produce. They are unbiased and objective, and we do not accept payment for them or for inclusion or more frequent updating. We also display advertising, which we work hard to make relevant, and we label it clearly. This is similar to a newspaper, where the advertisements are clear and the articles are not influenced by the advertisers’ payments. We believe it is important for everyone to have access to the best information and research, not only to the information people pay for you to see.

I quote this not for any “gotcha” purposes but rather the reverse. To me it indicates the depth and strength of the Google founding belief. (For the record, and as has been reported in articles and books about the IPO: As a friend of some Google leaders I discussed the themes and emphases in this letter with them before it came out, although I have had no business involvement with the company. That exposure does equip me to say that the founding statements were sincere.)

One of Ramaswamy’s points is that the only thing stronger than a founding vision is the imperative of the ad-based business model. The Google of 2000 might have imagined it could stop short of maximizing ad revenue on its search pages. For any ad-based company now, failing to do so would just be negligent—leaving money on the table.

“Ten years ago Google spent a billion dollars on search technology, and earned thirty billion,” Ramaswamy told me. “Now they spend a billion, and make a hundred billion.” It’s a good business proposition, and a worsening customer experience.

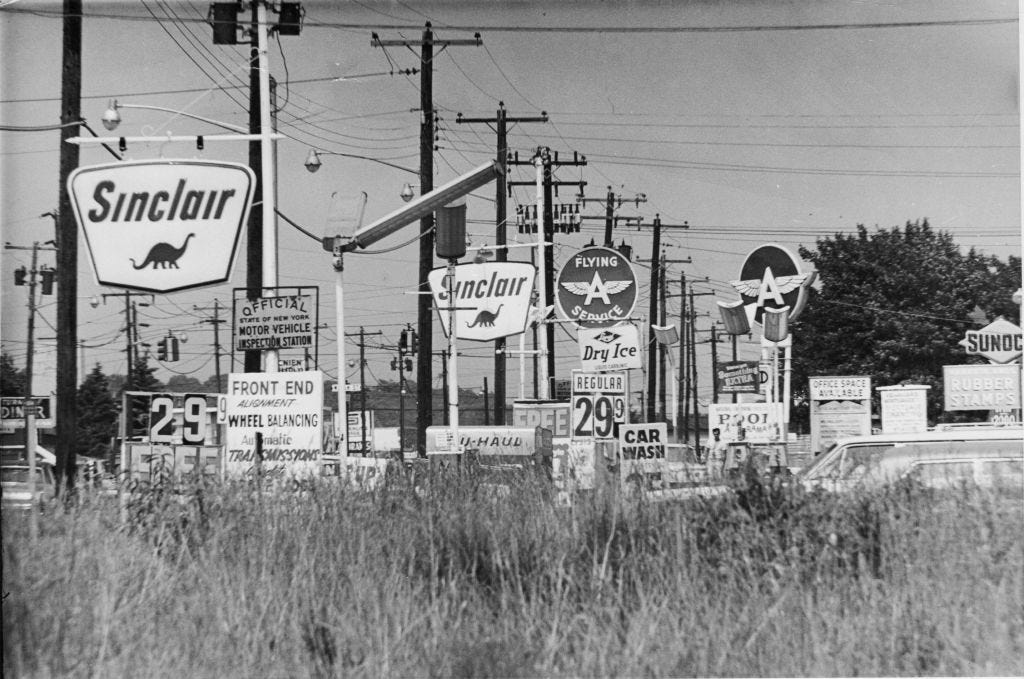

One version of this ad-and-attention-driven logic led cable TV channels to show wall-to-wall Trump rallies in 2015. How could they do otherwise? So many people were tuning in. Another version has given us Facebook and its scar upon the world.

In Google’s case, according to Ramaswamy: “The inexorable end point I saw was that non-commercial queries would only feature content from Google, while commercial queries would only have ads.”

Apart from its other bad effects, this model worsens the current information ecology. As visual and other cues denoting paid ads dwindle, “this has essentially created a Flat Earth view of the world,” Ramaswamy told me. “Everything looks this same. Nobody knows what to trust online.”

There is no point in casting blame about this situation. It’s just business. If you get annoyed by the still-increasing number of ads on “free” broadcast TV, you stop watching and instead pay for a streaming service. If you don’t like the ads on AM or FM radio, you stop listening and instead pay for podcasts, audio books, or Spotify.

And if you’re annoyed by the by the growing burden of ads on a free search service, you look elsewhere. This is what I have done, with the for-pay alternative that Ramaswamy and his colleagues are creating.

Building a different model

Sridhar Ramaswamy left Google three years ago and soon afterwards, with a former VP of Monetization at YouTube named Vivek Raghunathan, co-founded their new search company, Neeva. I asked Ramaswamy whether the name “meant” anything; he said it was just a name.

The big idea behind the company is that it would solve the ad-pressure problem by not running ads at all. Its revenue would come from subscribers, rather than advertisers. The founders’ vision for this tech startup is that by considering subscribers (not ad agencies) as their real customers, they could produce a fundamentally different and better product.

In entertainment terms, this is the Netflix or HBO model, in contrast to ad-based “free” broadcast channels—or ad-clogged cable channels. Compared with them, Neeva’s subscription cost will be less. The service is still in the “free introductory” stage of signing up users. I’ve relied on it on that basis for about six months. When it starts to charge, Ramaswamy told me, the rate will probably be around $5 per month.

When the time to start paying arrives, I’ll enroll as promptly as I did for the original Gmail. That’s based on what I’ve seen myself.

Fortunately you don’t have to believe me. The free-trial signups are still available, at Neeva.Com.

Some FAQs

As you’re considering this option, a few other relevant points:

How does it work, as a business? How can any startup dare compete with the mighty Google team?

I’ve spoken with Ramaswamy several times on this subject, and I’ll save the details for another time. You can hear directly from him, in an hour-long “Invest Like the Best” podcast here, and see a number of related podcasts on that same page.

In general: the software approach uses many new tools from the AI era; the hardware expenses are reduced by the rent-don’t-buy possibilities of cloud-computing; Neeva has some advantages in starting with a clean slate, and handling only a minuscule fraction of Google’s worldwide traffic (and doing so only in English); and eliminating ads removes many other complications. And, Netflix-style, they’re aiming at a smaller but significant audience. Turn to his podcasts for more.How well does it work, as a search engine? For me, it works just fine. I’ve used it for 99% of my searches in the past few months. But see for yourself.

What difference does it make? Again it’s a matter of personal taste. But for me it’s made an enormous difference to just get the results, without wading through a bayou of ads. Think again of the TV comparison. If you’ve been watching a streaming series, and then go back to broadcast, you think: Why should I be watching another pharmaceutical ad? Why am I listening to 1-877-Kars-4-Kids?

Why else does it matter? This week Neeva announced an initiative to reduce the spread of disinformation. It also emphasizes sharing revenue with news sources. Reinforcing credible journalism is a very big theme for the company, which I’m not going into now but may revisit.

Is it really new? Of course this is not the first or only alternative to Google search. Along with Bing, the best-known is probably DuckDuckGo. I’ve used and liked these other services, and especially admire DDG’s emphasis on privacy. Neeva also has extensive privacy protections—and to the best of my knowledge is the only major search alternative with no ads at all.

Compare, contrast, and see what you like.

You can find many other details here and here, But, mainly, try it for yourself.

I still live my life with Google products. I use Gmail, Google Calendar, Google Advanced Protection, Google Earth, Google Maps, Google Docs, plus others I’m not even thinking of now. And I’ll keep doing so.

But my default search engine now is Neeva.com.

Let me know what you think.

Thanks for bringing this to our attention ... signing up to try it.

A shame you had so much integrity as not to accept what Google must have offered you in the IPO. You'd have a small jet, instead. Not giving up Maps, right? The most incredible information store I know. Arrived late using Street Views, which I intend to master thoroughly before I lose mobility.