About That Passenger Who Landed a Plane

The pilot passes out, and a passenger takes the controls. It's a surprisingly common nightmare for many people, a heroic dream for a few, and a rarity in real life. Here is what happened in Florida.

This is an aviation-related post, about a positive development that drew attention this past week, amid other bad global news. It was the story of the passenger who, reportedly with no previous flight experience, safely and smoothly landed a Cessna 208 Caravan airplane in Palm Beach after its pilot passed out. Many stories about it are listed below.1 They include one titled “Miracle in the Air” from the FAA’s own Medium account, which provides inside detail about teamwork among the air traffic controllers who, over the radio, spelled out the steps required to get from the sky to the ground.

People inside and outside the aviation world have been fascinated by this episode, and gratified by its safe outcome. A few radio exchanges between Darren Harrison, the man unexpectedly at the controls, and Robert Morgan, the air traffic controller who talked him through the descent, were captured on LiveATC.net. They’re the ones quoted in nearly all news reports, starting with Harrison’s first report that “my pilot has gone incoherent” and “I have no idea how to fly the airplane.” Most of the controller-pilot discussion after that was on another frequency and does not yet seem to be online.

If and when the full tapes become available, people in the aviation world will study them eagerly, to hear exactly how the controllers, sitting on the ground, could give Harrison a real-time course in how to steer, control, and land an airplane. Most air traffic controllers are not themselves pilots. Part of the good fortune in this case is that Robert Morgan, the controller who mainly talked with Darren Harrison, is not just a pilot but also an experienced flight instructor. So this was not the first time he had told someone about the basic function of knobs, buttons, and other flight controls—though of course normally he would be doing this not over the radio but from the right seat of the cockpit, with his hands near the controls if the student in the left seat was having problems.

I’ve frequently quoted LiveATC.net recordings to illustrate the practiced calm competence of air traffic controllers and others who have made the air-travel system so remarkably safe. For instance here and here. Typically the greater the pressure, the less anxious the controllers somehow sound. I can’t wait to hear on forthcoming tapes how all involved exchanged information, and handled uncertainty and emotion, during the nearly 40 minutes between the first emergency broadcast and the near-perfect touchdown.

Here are some of things I’ll be listening to hear:

The big picture: landing an airplane is like riding a bike.

That’s the good news. And it’s the bad news.

—The good news is that just about anyone can learn to ride a bicycle, and just about anyone could learn to land a plane.

—The bad news is that just about no one can do either of these things without learning how. Almost no one can get either of them right on the first few tries.

How many children do you know who have seen a bicycle for the very first time—a real two-wheeler, with no training wheels—and then just pedaled away smoothly, without tipping over or skinning a knee? For me, it’s the same as the number of people I know who have taken the controls of an airplane for the first time and smoothly and successfully landed it on their own.

I’ve never seen anyone do either.

What’s involved in both cases is developing a set of visual, sensory, 3-dimensional, and other muscle-memory skills that let you handle processes that are complicated to describe, but that become “natural” when you’ve done them often enough. (See also: learning to speak your own native language.)

Most adults have been on bicycles enough times to know how it feels when you lean while going around a curve, or what it’s like when a hill becomes so steep that you can’t keep the bike going fast enough. But children don’t start out knowing that. They have to learn.

Something similar is true in aviation. Nearly everyone who has made a solo flight knows the “sight picture” to expect as you’re guiding a plane toward a runway for landing. But as with biking, you don’t start out with that knowledge. Yes, flight simulators can help, a lot. But doing it for real, the first time, with a real airplane heading toward contact with a real strip of pavement, is still different.

That’s one thing we’ll want to hear from the tapes: how someone could be talked-through what usually must be an accumulated muscle-memory experience.

Steadying the plane in the first place.

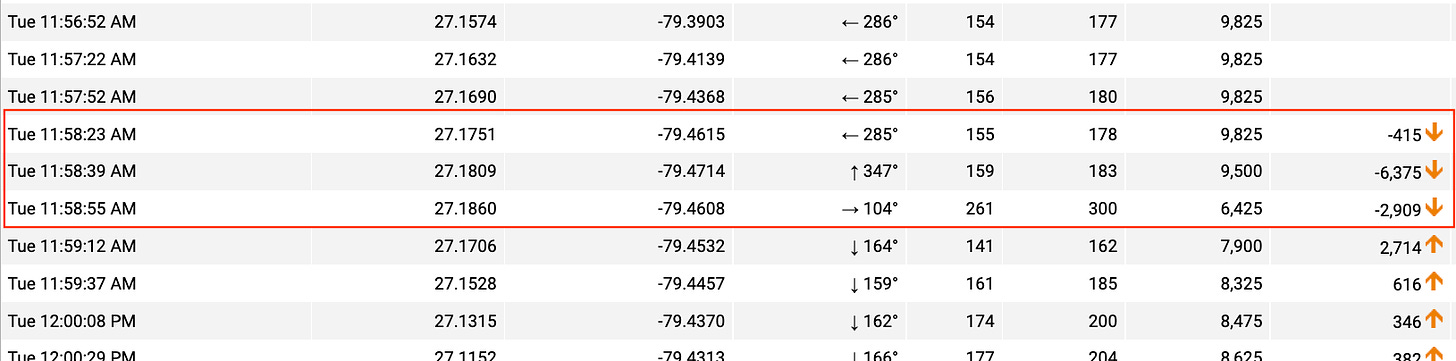

According to news accounts, when the regular pilot passed out, he slumped with his full body weight across the airplane’s control yoke. That put the plane into an extreme power-on nose drive, The chart below, from Flight Aware, shows that the plane lost 3,000 feet of altitude in about 16 seconds. That was a descent rate of more than 6300 feet per minute. Very few civilian pilots have ever been in a dive that dramatic. (I view it as “steep” when I’m descending at 1,000 feet a minute in our Cirrus.)

Simply arresting that dive, which in another minute would have led the plane into the ocean, was the first part of the achievement. As the Flight Aware chart shows, the plane kept plunging for a while, then ballooned back up, then was under remarkable altitude-and-direction control for the rest of the flight. It will be enlightening to hear how this occurred.

What else this plane—and pilot, and support team—managed to do.

The FlightAware path shows several distinctive things. I’ve highlighted some in red. On the right, the moment when the regular pilot passed out. On the left, the approach-to-landing at Palm Beach airport. And at the bottom, a graph of the speed-and-altitude anomalies.

— One of the important events, highlighted in the rectangle on the lower graph, is the altitude disruption when the pilot passed out. The plane was genuinely plunging toward the sea. Scenarios like this are why Cirrus airplanes like the ones I’ve flown have their built-in full-airplane parachutes, in case of emergency. It’s also why every airline flight you’ve ever taken has two pilots in the cockpit.

—Another is the smooth curved flight path toward Palm Beach, followed by the course-reversal setup for an approach and landing there.

Among the findings that will be most interesting on the full tapes is to know whether (a) the controller taught the pilot how to use the autopilot to direct these parts of the flight—the approach and landing at Palm Beach—which would be impressive. Or whether (b) the passenger-pilot carried out these stages of flight purely hand-flown. That would be at least as impressive, in a different way. And it leads us to:

Why landing a plane is hard — until you learn how.

What’s hard about riding a bike, until you learn how, is making it go fast enough that it stays up.

What’s hard about landing a plane includes the following elements, which are distinct from the other parts of “learning to fly”—weather, radio work, regulations, avionics, mechanical and electrical systems, etc.

You’re intentionally pointing the plane toward the ground. This can be disconcerting.

You have to maintain the “sight picture.” You can judge whether you’re on the right vertical descent path, by how the approach end of the runway looks as you head down. When the winds are smooth, this can be like riding an escalator down toward the runway. It becomes second nature, just like judging the traffic flow when you’re changing lanes on a busy freeway. But it’s not first nature.

You have to manage step-downs in altitude and speed. Planes typically cruise at speeds that are many multiples of their proper touch-down speed for landing. They need to reduce the speed in predictable increments —meanwhile while descending, which (unless offset) increases the airplane’s speed.

Managing the speed, and altitude, and alignment through these processes again becomes as natural as guiding a bike in a turn. But not the first time—or, for most people, the 10th, or the 50th.You have to manage “pitch and power,” which I’m not going to get into. Nor the use of “flaps.” Again, everyone learns to do this by muscle memory, but no one starts that way.

You have to manage winds. When there’s a crosswind, which seems to be most of the time, you “crab” into the wind, pointing the plane’s nose upwind so that its course remains aligned with the runway. And then there is “wind shear,” and allowing for “gust factor.”

You have to manage the “flare.” The difference between what feels like a “rough” and “smooth” landing often comes down to a difference of a few inches, and a few knots, in how the plane goes through the last little bit of descent.

Everyone has smoother and rougher landings—depending mainly on shifts in wind in that last little stretch. I’ve never seen anyone do this smoothly the first time.

Which in turn brings us to:

What the controllers could not do.

Except for airliners equipped for so-called Cat III “Autoland” approaches, and recently some small-airplane counterparts, the final 200 or so feet above the ground, and especially the final few dozen feet and inches of alignment and descent, are beyond an autopilot’s reach. Or control by anyone other than the person at the controls. That last stage must be managed by hand, and eye, and experience of having done this before.

None of the controllers helping Darren Harrison could have told him exactly what to do in those final few seconds. But he appears to have done it exceptionally well.

The Washington Post quoted an airline pilot on what occurred:

JetBlue pilot Justin Dalmolin told WPBF, which first reported the story, that he had to wait to land his plane as air traffic controllers guided the Cessna’s passenger into the airport. What the passenger did was no easy feat, Dalmolin told the station.

“The level of difficulty that this person had to deal with in terms of having zero flight time to fly and land a single-engine turbine aircraft is absolutely incredible,” Dalmolin said: “I remember ... when I first started flight training I was white-knuckled and sweating.”

Could most people have done this, if called to the cockpit? I don’t know. But this team appears to have had providence, teamwork, and remarkable skill on its side. Congratulations to them all.

Stories are from: the Washington Post, the Sun-Sentinel in Florida, NBC News, Florida news stations WPBF, WPTV, and WESH, the aviation-safety site Kathryn’s Report, and the FAA’s Medium post.

As a housekeeping matter, with an aviation angle, I’ll mention that Deb and I have been on the road, in circumstances that involved a lot of small-plane aviation, for most of the past two week—in Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, and most recently Arkansas. Details of all of that to come.

Of course, us Fallowsites knew this was coming and what an absorbing piece it is. I've often wondered how I would do in a situation like this. What aviation nut hasn't? My 10-year-old Alaskan grandson spends hours watching take-offs and landings on his computer, and acquainting himself with different planes' instrument panels. When asked if he thought he could land a plane the way this guy did, he said: "If it was a 737 I could." Which brings up a question, Jim. how difficult was it for Sully to land his plane on the Hudson River? Another question: If the incapacitated Cirrus pilot passed out on the yoke and the plane was in a super-steep dive, how would the passenger have been able to get the pilot reclined back in his seat? What a story!

Here's a video showing a recent landing at Billings, MT in my Beechcraft A36 Bonanza. The end of this clip gives you a good idea of what the final stages of a typical approach and landing look like.

https://youtu.be/L82zBnsb614?t=901