A Few Questions (and Some Answers) About the Latest Airline Meltdown

The modern airline system is much more ‘efficient’ than it used to be. And vastly safer. But it can also be more susceptible to ripple-effect shutdowns, like the one this week.

There’s a lot we don’t know yet about the system-wide Southwest Airlines collapse this week. What we do know mainly includes the hardship for huge numbers of people through the height of holiday travel.

Here are a few questions I would ask, and presumptions I would bring, based on having written about Southwest in its founding days for Texas Monthly back in the 1970s, when both that magazine and that airline were new.1

1. Is Deregulation the Root Problem?

Answer: Sort of.

An annoying answer, I know. But as with nearly everything in aviation, things are complicated. And the complications in this section boil down to: ever-greater ‘efficiency’ in the industry, means ever-shrinking margin for error when things go wrong. As they just have.

Before sweeping airline deregulation in the late 1970s, the business aspects of flying were more tightly controlled than virtually any business is now.

Every fare for every interstate air route had to be approved by government regulators at the Civil Aeronautics Board. There was none of the second-by-second roulette of pricing we have grown accustomed to. In those days there were hardly any “budget” airlines, or $99 deals. Southwest Airlines was an exception. It got its buccaneer low-price start because its routes were entirely within Texas, and less subject to CAB control.

Most details of interstate route structure and flight schedules were also government-run. Federal regulators had to approve which cities an airline would serve, and how often, and at what specific times, and at what price.

The air-travel system was obviously different from buses or trolleys used in public transit. Among other things, it had far more luxury touches, as in the photo above—which is unrepresentative but evocative of the era. Average ticket prices were so high that airlines overall had an elite customer base. (Thus the hoity-toity term “jet set.”) But the regulatory mindset was that of a high-end public-transportation service, connecting the country through air travel.

I stressed, above, the post-1978 change in business aspects of airlines, because the operational aspects of air travel are still very much under governmental control. Airlines fly public airways, through publicly controlled airspace, to publicly run airports. They deal with air traffic controllers who operate according to FAA rules. Safety announcements by flight attendants sound the same on every airline, because staffers are all reading from FAA-approved texts. Inspection schedules, no-fly “airworthiness” checklists, obligatory rest hours for crew—these and many other operational details are still mandated by the FAA.

A revolution in business rules.

In contrast to this operational continuity, the business aspects of airline travel were completely overturned by the Aviation Deregulation Act of 1978. Students of history will notice that this change was part of Jimmy Carter’s deregulatory agenda, not Ronald Reagan’s. As has often been reported (and as I knew firsthand as a Carter aide at the time), a crucial Senate ally was a young staffer for Senator Ted Kennedy named Stephen Breyer. Yes, the same now-retired Mr. Justice Breyer.

Was airline deregulation overall “good” or “bad”? I can argue either side, and whole bookshelves are filled with volumes making both cases.2 To boil it down:

The best thing about the deregulation era is that it has coincided with the safest era of travel the world has ever seen. Data point: in the past dozen years, U.S. airlines have conducted more than 10 billion “passenger journeys”—one person making one trip. Through those 10 billion passenger journeys, a total of two people have died in U.S. airline accidents. Being wedged into seat 38E may not be the most enjoyable way to spend your time. But statistically it is the safest.

Was that safety revolution because of deregulation? That’s a hard case to make. Pilots, controllers, engineers, dispatchers, air crews, regulators, weather experts, and countless others have all played a part. But the two trends have happened over the same years. Deregulation has not come at the cost of safety.3The other side of deregulation is that it has led to the ruthless marketization and ‘efficiency’ of air travel, with all the good and bad that pure bottom-line market-mindedness implies.

The “good” side: in the olden days planes often flew half-full. Which was “wasteful”—of fuel, opportunity cost, in many other ways. Now they’re jammed, with every inch of onboard space put to maximum use. Pleasant: no. Efficient: yes.

And while economists debate exactly how much average ticket prices have fallen, it’s undeniable that “bargain” fares have changed air travel from an elite to a mass experience. On a typical day, some 3 million people show up at U.S. airports for their flights. This means that in the course of a year, more than three times the total U.S. population has gotten onto a plane.

The “bad” side of market-mindedness is related. Everything is more crowded. Everything is more like a bus. And the whole air travel experience has become one more demonstration of a “winner take all” economy. The “premium” cabins are ever more spacious and luxurious. The other seats are ever more cramped. You get what you pay for, and you see where you rank. (To be fair to Southwest, it’s an exception to this trend. All seats are the same.)

But beyond its cultural signals, market-minded aviation has another significant operational effect. Overall there’s less slack, because slack means economic waste. It’s extra equipment, extra spare parts, extra crew and staff that you could call on in an emergency, but that in normal times is just redundancy and “overhead.”

This means: If you’re bumped from one flight, there’s no space on the next. If an avionics failure grounds one plane, there aren’t others sitting around to use. If a plane misses its takeoff or landing slot, congestion may mean it waits half an hour for a clearance — meaning missed connections.

All of this is more efficient for the airline companies. But the costs—delay, inconvenience, hassle, uncertainty—are diverted onto the travelers. An overnight at the airport when a connection is cancelled, a three-day delay before checked bags arrive, a coffee-shop voucher for an unexpected six-hour stay in the airport. These aren’t directly priced into airline profit-and-loss figures, but they are costs of a “no slack” system that customers, rather than the airlines, usually bear.

Pure marketization gives us Amazon and Wal-Mart, versus the downtown store. It gives us Uber, versus the taxis. And in airlines it has given us the radical concentration of carriers, leaving us mostly with American, Delta, and United—plus Southwest, with all that has been good in its model, and all that is disastrously bad.

To sum this point up: the de-regulation era, which began before most of today’s Americans were born, means that airlines operate with less economic oversight, and less slack. That’s part of this week’s problem.

2. Is it all about ‘hub and spoke’ versus ‘point to point’?

Answer: No.

One big theme in recent articles is that Southwest’s problem is its “point to point” route model, versus the “hub and spoke” model of the other airlines.

Hub-and-spoke of course means that you go through some connecting site, if you’re traveling to or from a smaller city. That’s how United operates—Dulles, O’Hare, Denver, etc. And Delta— Atlanta, Salt Lake City, Detroit, etc. And American —Miami, DFW, Phoenix.

Point-to-point means you don’t have to change planes or connect. Southwest has flights from Tulsa to Las Vegas, from Spokane to Sacramento, from Tampa to Providence.

Here is a crucial point now being neglected: both models are fragile.

Point-to-point is fragile in the way we’ve just seen. If that Southwest plane doesn’t make it to Tampa from Providence, then the outbound flight to Cincinnati will get screwed up, and on from there. It’s like a breadcrumb trail.

But over the years we’ve often seen the fragility of the hub model. Ever been stranded at O’Hare because of snowstorm? In Denver because of icing? At SFO because of fog? This is the glory of routing so many flights through hubs.

The hub model involves two main problems.

—One is congestion. More and more traffic is crammed into a finite amount of space. Space for runways, for parking, for landing slots, for baggage handling, for rental cars, for everything. It’s all operating above designed capacity.

—The other is ripple-effect consequences. When something goes wrong in a busy hub, the effects can be felt thousands of miles away. People coming and going from the East or West Coast can be stranded, because of snow in the Rockies or Midwest (where they have to change planes).

Back in the 1960s, Arthur Hailey wrote a best-selling novel called Airport about the way a snowstorm in Chicago tied up air traffic nationwide. (It became a hugely successful movie that was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar, led to three sequels, and indirectly inspired the wonderful Airplane! series of satires.) Hub traffic is much more concentrated now.

So if both the hub-and-spoke model, and point-to-point, are vulnerable, what just happened?

3. It is all about incompetence, lack of accountability, and greed?

Answer: Yes, that appears to be the case.

Any of this era’s major airlines could have been disrupted by this week’s storms.

American, Delta, and United all were delayed and then quickly recovered. Southwest did not—for reasons that now appear to be entirely its own fault.

On current evidence, their base-level failure was not having a way to keep track of customers, and crew, and baggage, and airplanes, and everything else involved in keeping a complex system moving.

Modern air travel is complex on a level rivaling the D-Day invasion. And modern first-world airlines have geared themselves up for that challenge.

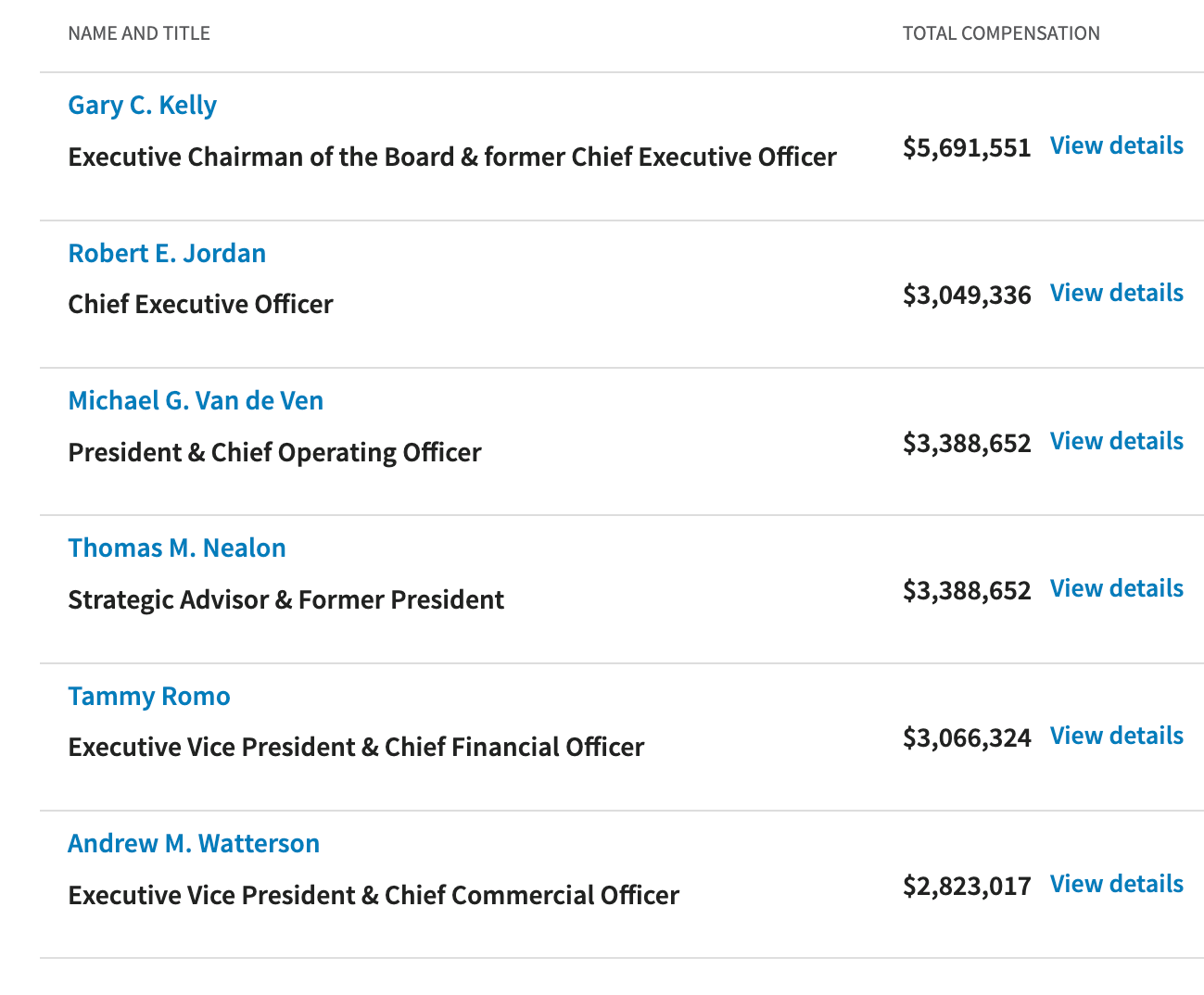

It appears that one of them did not—despite receiving billions of dollars in public aid during the pandemic, despite having spent billions on stock buybacks that benefited only their shareholders, despite very generous pay for its executive leadership, as shown below.

This is not the Southwest I wrote about, under Herb Kelleher, decades ago, for the Texas Monthly. This is market-mindedness in a bad way. Those responsible should be held to account.

For starters, it wouldn’t be a bad move for these people to kick in some of their pay to compensate those they have distressed.

I’ve written two books about the changes in the industry before-and-after the huge deregulation of the late 1970s. One was Free Flight, which came out just before the 9/11 attacks and discussed the rise of hub-and-spoke aviation. The other was China Airborne, published 10 years ago, about the way China’s aerospace ambitions were modeled on, but differed from, those in the U.S.

Also, as a 20-something White House speechwriter during the Carter administration, I worked with the “Father of Airline Deregulation,” Alfred Kahn, to write some of the presentations, press releases, and speeches about the new approach to air travel. Of course I did not make any of the policy.

Also, and as a subject for another time: aircraft- and engine-makers have become steadily more fuel-efficient, and are working hard toward reliance on “sustainable aviation fuels.”

Here is another comment from a personal email message.

(As I say, I will "intend" to have an improved-and-streamlined comment section and function here.)

It is from a reader in the western half of country:

>> "With all due respect, I beg to differ. Southwest's meltdown is not just about some isolated problems at a single airline; rather, Southwest's debacle highlights flaws not only of the aviation industry but of this era. The core problem, I think, is that American society has socialized risk for important industries while allowing the benefits of our increasingly productive economy to be captured by a relatively small elite.

"The airline business is a prime example. Due to failures to enforce antitrust laws, the United States is now beholden to just four airlines (Southwest, American, United, and Delta), each of which is too big to fail. So in troubled economic times, the American taxpayer has been left to repeatedly rescue these airlines.

"I can only hope that President Biden and Secretary Pete have learned the hard political lesson from TARP's fallout. Yes, TARP was a necessary evil to save the banking system from collapse in 2008. But President Obama and the Democratic Party made a generational error by bailing out the bankers and then holding no one accountable for causing a global economic calamity. Main Street felt the pain from the recessession for years while Wall Street executives quickly returned to collecting bonuses that were essentially subsidized by the American taxpayer. It's little wonder so many Americans soured on politics and lost faith in the basic fairness of American society.

"Fast forward to 2020. After COVID hit, the American taxpayer (again) bailed out the aviation industry (including Southwest) to the tune of $37 billion. Unfortunately the result was not a social compact between the industry and the American citizens whose taxes insure and subsidize the industry. Instead these airlines enriched their executives and shareholders at the expense of their employees and customers. These airlines have also spent millions of dollars lobbying for a favorable regulatory environment that, as tens of thousands of aggrieved Southwest customers are experiencing this week, shifted financial risk from the airlines to their employees and customers.

"The reason Southwest continues to blame the weather for its own systemic failures is because Southwest doesn't want to be financially responsible for the airline's systemic failures. Southwest wants its employees and passengers to be stuck subsidizing the true costs of the airline's mismanagement. Tens of thousands of Americans had their holidays ruined by Southwest, and many thousands incurred thousands of dollars of expenses to cope with Southwest's meltdown.

"The meltdown of this single airline thus poses a stress test for the basic fairness of our society. Will our federal government take the side of citizen-consumers, or will our government again yawn at corporate malfeasance? Will President Biden and Secretary Pete hold Southwest accountable by ensuring that passengers are properly compensated, or will Southwest (and its shareholders and executives) be insulated from the true costs of this debacle?

"It will be political malpractice if President Bident and Secretary Pete fail to hold Southwest fully accountable for this fiasco.

"P.S. I'm writing from home and was not personally impacted in any way by Southwest's meltdown." <<

'Soon' (probably 'next year') I will use one of Substack's many features to set up a special comment-zone thread for evocative topics like this. I'm grateful for the excellent accounts and analyses like those below.

For the moment, I'm weighing in with a "comment" to post two interesting personal emails I have received, related to comments like the ones below.

First, one from a very experienced flyer, on the phenomenon of last minute through-the-nose fare increases:

>> "I am now sitting in the United Club at SFO waiting for the red eye to DC tonight. I have a last minute near emergency that I must attend to. The round trip from [a smaller west coast city] to DC and back is costing me $3k since I just booked it this afternoon. There is one seat left in first class. I can have it for another $2k.Never mind that I have over 4 million lifetime miles on United, that I am in the Global Services top of the United flyer hierarchy, I probably can’t get that seat unless I pay up which I am not going to do.

"I think there is something wrong with the pricing of tickets on a less time higher price basis. People have emergencies they cannot predict. I feel they should not have to pay through the nose because they must book on unexpected short notice...

"I am not sure there is any real competition between today’s airlines... I am in [the west] at this time of year and typically fly to DC through SFO or Denver. United owns both those routes. United totally owns the flight to SFO. Sometimes I pay more for that half hour hop than for the SFO -IAD flight.

"I used to like to fly. It has become increasingly a pain." <<