What We've Learned About the Deadly Crash Over the Potomac.

And why honest investigations of disasters like these are imperative, in order to make flying safer.

Slide from the NTSB’s public hearings this week, charting the paths that led an Army Black Hawk helicopter (path in yellow) to fly into a commercial airliner (in blue) in the skies over Washington DC. (NTSB graphic.)

This post is about aviation safety, based on the deadliest US airline crash since 2001. This was the 2025 collision, over the Potomac, between a US Army Black Hawk helicopter, on a night training mission, and a Bombardier CRJ700 regional jet, inbound from Wichita, Kansas, and about to land at National Airport in DC. In that crash, which happened one year ago this week, all 67 passengers and crew aboard both aircraft were killed. These included 14 young figure skaters, returning from a competition and training camp in Wichita, and 14 more of their coaches and family members.

The National Transportation Safety Board has not yet released its full, official, “final” report on the incident. But this week it held a day-long public hearing that was a preview of nearly everything likely to be in that final report.

It included dramatic new illustrations, re-enactments, and data, and strong indications of who and what, in the end, would be judged most responsible for allowing the “holes in the Swiss cheese” all to line up.

The Swiss cheese metaphor is a common aviation parlance for times when small vulnerabilities in multi-layered, redundant safety systems—the holes in slices of cheese—all happen to align, and allow disaster to occur. In this case, as in most air disasters, there were missed opportunities to avert tragedy all around. But to me it looks as if the crew in the Army helicopter missed the most chances to prevent a deadly alignment of holes.

My purpose in this post is mainly to direct attention to several parts of the hearing that deserve broad public attention, as well as a new magazine article that also adds significantly to our understanding. And then I’ll add some of my own conclusions about things we’ve all learned.

I really do hope you’ll take to time to look at some of the presentations and discussions listed below. They’re detailed and compelling and range beyond what I can cover here,

This is a preview of the themes that struck me from the hearing:

The entire air-travel system over the Potomac—with the White House and Capitol sitting immediately on one side, and hyper-busy National Airport (plus the Pentagon) immediately on the other—had long been operating on a high-volume, high-stress, zero-margin-for-error basis. It had avoided crashes for decades, but its reliance on good luck, and round-the-clock hyper-competence by all involved, couldn’t last forever.

The “Swiss cheese” margin for error became paper-thin, and then disappeared, on that night over the Potomac, through a combination of fateful factors. They include but were not limited to:

Crucial details in radio transmissions that were blocked, because of aviation’s antique CB-style radio system—which, among other problems, kept the airplane crew from hearing what the controller was telling the helicopter, and vice versa. This limited each aircraft’s “situational awareness” of where the other was. An apparently defective altimeter in the Black Hawk, which could have made its crew think it was flying much lower than its real altitude. The crew apparently thought they were staying below the mandated ceiling of 200 feet as they neared National Airport. In fact they were flying much higher, and straight into the path of airliners, rather than safely below them. (The altitude at collision was 278 feet.) A crosswind that forced the helicopter to fly at a “crabbed” angle to maintain its course along the Potomac, and therefore pointed the cockpit away from where controllers expected the pilots to be looking. An air traffic control decision at National that led the doomed airplane to take a different final approach course from what the helicopter was likely expecting. Routine traffic-flow practices at National, to keep planes taking off and landing as frequently as the physics of runway space allow. The sheer visual chaos of nighttime landings at National, with city lights, airplane lights, helicopter lights, and other distractions. And many decisions by those in the helicopter that created new holes in the cheese. These started with the fundamental choice to operate a night-training mission in some of the most congested and tightly controlled airspace in the country, when they could have taken other routes or stayed away from the city altogether.More details on these points and others in the hearings and initial report.

There is no suggestion, in any of the data I have seen, that the regional airline crew created any new “hole” in the safety structure. To judge by the recordings of in-cockpit discussion between those two pilots, they were doing everything by the book in setting up for a safe landing at DCA. There is virtually nothing they could or should have done differently. The airline pilots had almost no way to avoid this tragedy.

There is zero suggestion in the data that Donald Trump and his then brand-new Transportation Secretary, Sean Duffy (who has zero aviation experience), were correct in their immediate, despicable suggestions that the crash was caused by “DEI practices” at the airlines and the FAA.

The day after the crash, Trump said at a press conference that the Obama and Biden administrations had hurt the FAA with diversity programs, and that they had considered it “too white.” By contrast, he said, “We want the people that are competent.” As it happens, it appears that the person who missed the most opportunities to prevent this crash was a white male.

But we’ll get to that. First a review of what we learned at this week’s hearings.

1) How things looked inside the cockpits.

I strongly encourage you to begin with this eight-minute NTSB video presented at the hearings. It very carefully shows what it would have been like, inside the cockpit of each aircraft, in the minutes leading up to the crash. Mainly it conveys how difficult it would have been for either of them to see the other.

Technical note: The NTSB videos mentioned here are all on YouTube, which means that you can speed up their replay to 1.5x or even 2x the real-time rate. I encourage you to do that except if you’re listening for messages from Air Traffic Control. In busy airspace like DC’s, these can sound like 3x speed even in normal circumstances. You should hear those at the same pace the pilots did, to get a sense of how busy this whole arena was.

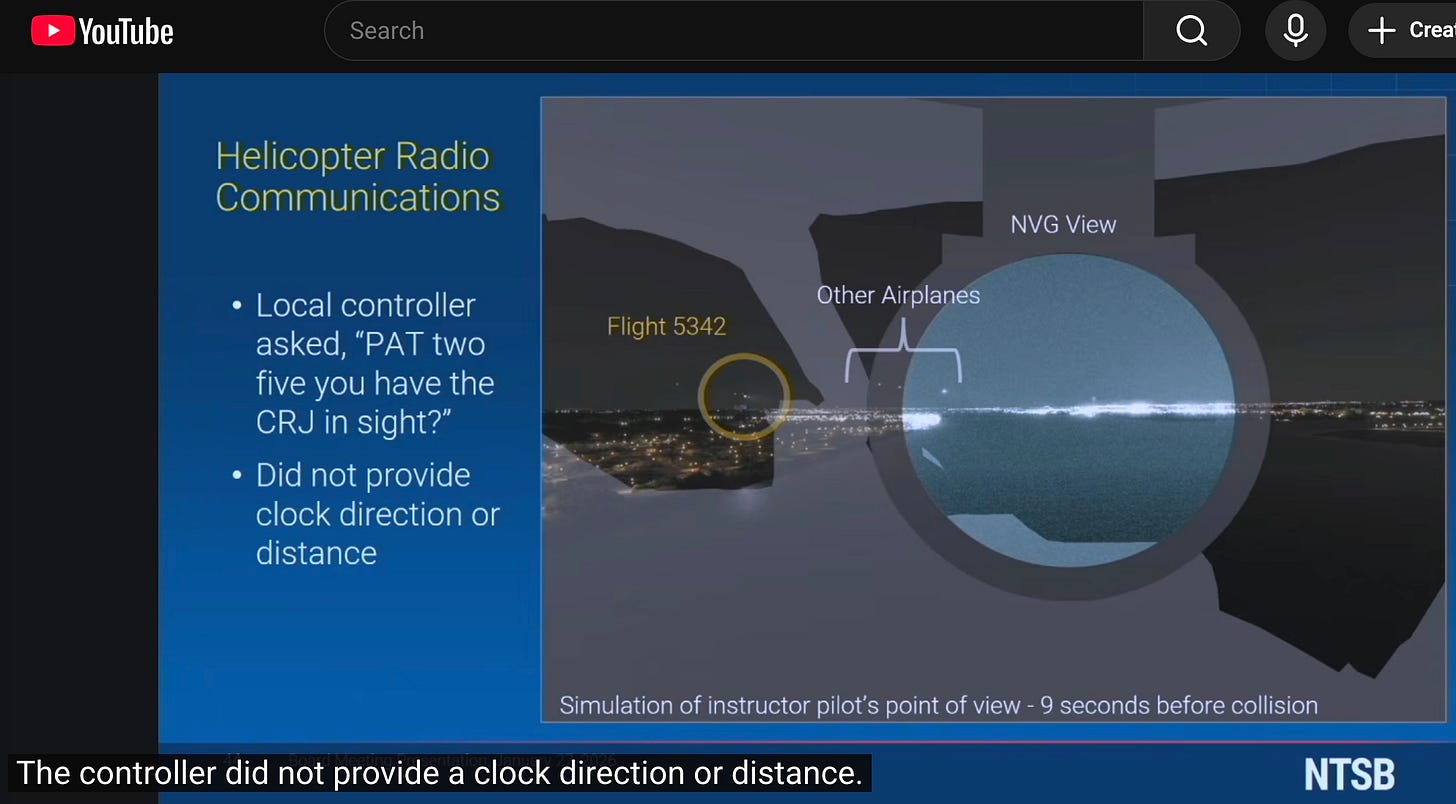

My reaction to this video—having flown a small plane over DCA at night during training in the 1990s, when such things were possible, and having dealt with night landings at several major airports over the years—is that it reinforces how fraught these moments of flight were, for everyone involved. The controller, for instance, is dealing with several helicopters, many inbound and outbound planes, and some other duties, in a nonstop rat-a-tat. Inside the Black Hawk, both pilots were wearing night-vision goggles. These would be useful during night missions in theaters of war. But in the crucial moments as they neared National Airport, these goggles significantly narrowed the pilots’ range of view. (As the video demonstrates.)

The first four minutes of this video simulate the view from inside the helicopter. You’ll see it flying right down the river toward downtown DC, with the Washington Monument, the Jefferson Memorial, and other landmarks clearly visible. You’ll also hear the DCA controller asking, twice, whether the helicopter crew had the regional jet in sight. Twice—immediately, confidently, almost by rote—the “instructor pilot” in the helicopter said “traffic in sight” and asked the controller’s approval to “maintain visual separation.” This apparently had become a routine request in this airspace, and was routinely granted. Unfortunately the pilot was looking at the wrong plane.

The second half of this video shows the view from inside the airliner. Again I’ll say: Its crew seemed to be doing everything by the book.

This is a high level of explanatory video work by the NTSB.

2) The ‘overview’ NTSB explainer.

Next, I encourage you to watch the overall introductory video with which the NTSB opened the hearing. It’s 12 minutes long; you can speed up parts unless you want to hear the real-time cadence of ATC broadcasts; and you will see a tragedy in the making.

Every fundamental what/why/how/who issue is covered in this video. Including the crucial fact that the helicopter crew knew that they had to stay below 200 feet altitude as they neared National, but they were almost 100 feet too high. In cross-country flight, a 100-foot altitude error is minor sloppiness. Crossing the final-approach path for a major airport, it left 67 people dead.

3) An NTSB briefing on helicopter practices.

Next, I encourage you to look at one of the NTSB’s staff presentations on what the helicopter crew was doing, and how they could have missed so many cues.

The whole hearing is nearly 8 hours long, and you can see it and links to all other relevant documents at the NTSB’s index page, here.

But I encourage you to see or listen to the several-minute presentation that starts around time 3:19 of the full board meeting presentation. It should come up if you click on the image below, which is linked to that part of the full-session video.

Among the important parts of this presentation: “Expectation bias,” from the Black Hawk crew. They didn’t expect a plane to be lined up for landing on Runway 33 at National (as opposed to the longer Runway 1, with a different final approach, straight from the south), and so they weren’t looking in that direction. Also habituation, especially in the request for “visual separation.” To re-emphasize: When the DCA controller asked, twice, whether the helicopter crew had the airliner in sight, the “instructor pilot” in the Black Hawk instantly answered that he did, as if by reflex, while looking at the wrong plane. He must have done that many times before, and it had always worked out. Until it didn’t.

This part of the NTSB assessment gets into the “situational awareness,” “human factors,” and “aeronautical decision-making” that lie behind most modern aviation tragedies. It’s well worth your time.

4) ‘The Last Flight of PAT 25.’

This recommendation is to a new article, by Jeff Wise, in New York magazine’s Intelligencer section. It’s here, and is a minute-by-minute dissection of what the two pilots aboard the helicopter were doing and saying in the two hours before they flew directly into the regional jet’s path.

Some details that stood out for me:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Breaking the News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.