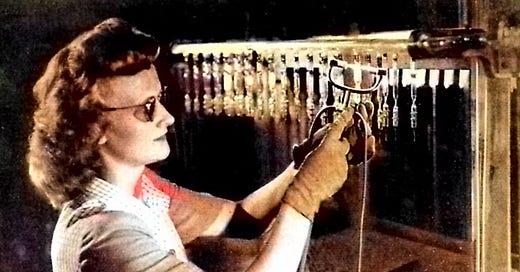

This photo from 1922 shows a worker at Bell Systems doing the advanced-tech manufacturing of that era, testing vacuum tubes while wearing protective dark glasses. Advanced-tech manufacturing is making a comeback in the US. (Colorized photo via Smith Collection/ Gado/Getty Images.)

Two weeks ago I mentioned that I plan to concentrate for a while on innov…