What Do We Know Now, About the Airline Crash in DC?

We're in a veil of ignorance. But that's nothing compared with the blindness and bigotry of the commander-in-chief.

Crews on the Potomac this morning, searching in vain for survivors of the collision of a regional jet and a military helicopter last night outside DC National airport. Even before the bodies were counted, national GOP leaders were ready to cast blame. (Photo by Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images)

This post is a set of questions and answers about the terrible airliner-helicopter crash last night over the Potomac outside DC National airport. It follows an interim update that I wrote yesterday a few hours after the event. (And please see update a few paragraphs down.)

1) How can I get the big picture, of what was happening and what went wrong?

For overall orientation I highly recommend this video recreation, below, from VASAviation. The site is run by a pilot based in Brazil who has made a specialty of matching Air Traffic Control recordings with radar and ADS-B tracks of how planes are moving through the skies. It’s a tremendous service.

This latest eight-minute VASA video takes you through the crucial stages of the unfolding DC tragedy. It shows the regional jet approaching from the south; the controllers recommending (because of wind) a shift in runway-choice for its landing runway; the military helicopter approaching from the north; the controller instructing the helicopter pilots to avoid the jet; and then, once things have gone to hell, the aftermath of controllers calmly-but-urgently routing inbound planes away from the accident-scene airport.

It’s all here. Some time-stamp notes, from me, are below.

My time-stamp guide:

-Around time 0:20, you’ll hear the jet, “Bluestreak 5342,” an American Airlines regional feeder inbound from Wichita, checking in.1 It is heading toward the airport from the south, and announcing that it is on the “Mount Vernon Visual” for Runway 1 at DCA.

“Mount Vernon Visual” is a standard up-the-river visual approach (charted here), toward a landing on National’s longest runway, Runway 1, which is nearly 7,200 feet long. That strip of pavement is known as Runway 1 not because of its primacy but because of its compass heading of 010 degrees. When planes are landing on that same runway headed south, it is known as Runway 19. (Why? Details below.2)

-A few seconds later, the DCA tower reports very strong, gusty winds from the northwest. The controller says: “Winds are 320 [degrees] at 17 [knots], gusts 25 [kts].” This means that a plane landing on Runway 1 will have a quite significant crosswind from the left. The tower asks if the plane can accept a switch to landing instead on Runway 33. This runway, 33, is shorter—only 5200 feet long, which should be no problem for a regional jet3—but was almost directly aligned into the wind at the time. The regional-jet pilots say OK, and agree to alter their path accordingly. (I’ve never been in command of a jet, but with those winds I’d always prefer a landing on 33 rather than 1.)

-At time 1:35, the DCA tower gives a heads-up to the Blackhawk helicopter (addressed as “PAT two-five”) about the regional jet (“the CRJ”) that is inbound for landing on Rwy 33.

And although the response from the helicopter crew does not seem to be included here, perhaps because it was on a different frequency (perhaps military UHF versus civilian VHF), the tower says, at time 1:42, “Visual separation approved.” That could mean, though the evidence is incomplete, that the Blackhawk crew had acknowledged the inbound traffic and said it would maintain “visual separation” from them.

IMPORTANT UPDATE: VASAviation has posted an update, which includes the responses from the helicopter crew. Its members clearly say “traffic in sight” and that they will “maintain visual separation.” See it here.

-Please watch carefully around time 2:15. You can see the tracks of the regional jet and the helicopter converging. And you can hear the controller asking the helicopter, “Do you have the CRJ in sight?” Then, a few seconds later, presumably after a positive reply from the helicopter crew: “PAT two-five, pass behind the CRJ.”

That is: a controller saw an impending problem. He appears to have asked the helicopter crew about it, and to have directed them to avoid it. Somehow that didn’t happen.

-Starting at around time 4:50, you’ll hear transmissions from “MWAA,” the Metropolitan Washington Airport Authority, saying Crash, crash, crash, and moving into the ground-response role. Every minute of this recording is dramatic, and shows grace-under-pressure.

2) Who are the main players, and what do we know about what they did?

There appear to be three main figures in this doomed drama:

-The crew of the regional jet, flying as American Eagle from Wichita to Washington and known as “ 5342.”

As far as I can tell, as yet there is no suggestion that they did anything amiss. They had to shift their intended landing point from Runway 1 to Runway 33, but that’s not a huge challenge—at big, busy airports, you can be switched from one runway to another while on final approach—and as mentioned it gave them much more favorable winds.

-The air-traffic control staff on duty, at the DCA tower and the larger DC-area “approach” facilities.

There will be tremendous attention to what the controllers knew, when they knew it, what they should have known, what they said, and what they should have said.

It is worth noting that the controllers were the immediate, unsubstantiated, bigoted-sounding objects of attacks by Donald Trump himself and many of his claque. Maybe the controllers will prove to have been at fault. Maybe the larger system in which they work was a problem. We’ll see; there’s no immediate evidence on that front.

Conceivably evidence might emerge. But to say that they (or anyone else) is to blame at this point is pure reflex, or bias. We don’t know what we don’t know.

-The helicopter crew. Again, it’s early. But on those early impressions, two things draw attention.

One was the sequence of reminders from the DCA controller about the crossing CRJ traffic, and the (apparent) replies from the helicopter crew that they had it in sight. Were they looking at another plane? (I’ve done this myself — called “traffic in sight,” and only later realized that I was looking at a different plane from what the controllers were calling out.) Were night-vision goggles a factor? Did something else happen? Right now we don’t know.

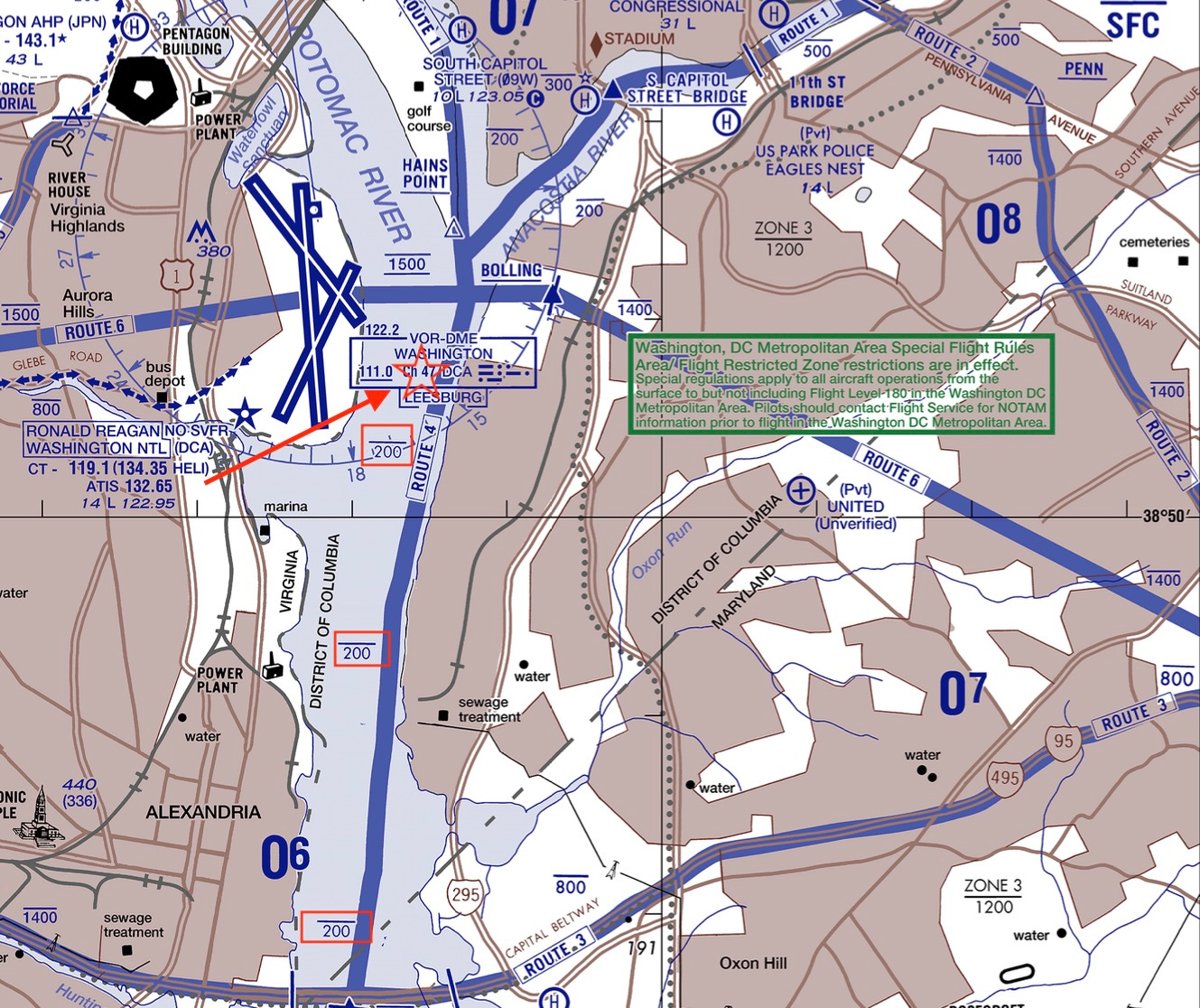

The other is the normal altitude limits for helicopters working this busy over-the-Potomac corridor. As shown on the FAA chart below, helicopters taking “Route 4” down the Potomac, which crosses the landing paths for DCA traffic, are supposed to stay strictly below 200 feet of altitude. (I’ve highlighted the “200 feet” limit in red. That straight line above the number 200 means “do not go any higher than this.” I’ve added a star and arrow very roughly indicating the collision site. NOTE I’ve updated this chart, to suggest a further-north location of the approximate collision site.)

At two hundred feet or less, the helicopter would presumably have been below the inbound plane’s descent path. Did it get too high? And if so, why? And why did they not see the plane? Again we don’t yet know.