Two New Possibilities for the ‘Times’

A very short to-do list for the paper's new leadership.

Congratulations to Joseph Kahn on being named the next Executive Editor at the New York Times. This is among the handful of trickiest and most challenging jobs in journalism and probably stands alone as the most influential.

Why trickiest? Because of the array of highly demanding audiences and “stakeholders,” many of whom come from opposing corners. Whoever leads the Times needs to worry about: the paper’s staffers. And its ownership family. And other stockholders. And its readers, who themselves differ on countless issues and love and hate its columnists. And the politicians who are unhappy with it. And the governments around the world that might want to block or censor it, or kick out its correspondents. And the book writers / film directors / Broadway producers / restaurant entrepreneurs / museum curators who all feel that their offerings should get more attention, or who are furious about or devastated by bad reviews. And the printers. And the advertisers. And the digital and other competitors. And back to the staffers again. And the readers. It doesn’t end.

And why most influential? Well, look around. Despite “decline of print,” despite “siloed news,” despite “misinformation”, despite whatever else, the NYT still has an agenda-setting power greater than any other U.S. news organization. This matters if we keep turning our amazing resources toward it. That doesn’t, if we don’t.

I don’t know Joe Kahn, though we have many mutual friends and overlapping experiences. He was leaving his final stint as a reporter in China, for which he won a Pulitzer prize (his second) with Jim Yardley, at just the time Deb and I were arriving in 2006. I have followed and respected his reporting over the years.

Through his reporting and management and technological experience, Kahn seems as well prepared as anyone could be for this role. And, as John Harris argues, he may be well prepared by temperament as well. Good luck and sincere good wishes to him.

Everyone starting a new managerial job is on the receiving end of others’ wish-lists for how to use the leverage that comes with a fresh start. It happens to new presidents, governors, mayors, any public officials. It happens to new parents. It even happens to newly installed editors.

Here is my two-point list. It starts from the premise that overall the daily New York Times is a miracle of journalism and imagination. Its range of coverage and curiosity and talent and means of expression has no peer. If you think of science, the arts, books, technology, climate, the culture-of-sports, global affairs, medicine and health, music, sustained investigation, food, games and puzzles, and on down a long list—and then you also imagine those topics being explored not just in words but also with maps, and digital graphics, and in a Chinese-language edition, and through podcasts, and more, you have an achievement worth appreciating every day.

But—as I have written roughly one million times over the past decade—there is, ahem, room for improvement in the paper’s framing of domestic U.S. politics. (Many others have also made this point. A few: Margaret Sullivan, Judd Legum, Jay Rosen, Greg Sargent, Dan Froomkin, Michael Tomasky, and of course the late and much-missed Eric Boehlert.)

Here are two things a new regime could do on that front:

1) Re-empower a Public Editor.

In 2003, because of a scandal that was highly embarrassing within the paper but (by modern standards) did comparatively little damage on the outside, the Times created a Public Editor position. It was a kind of ombudsman role. Its first incumbent, and one of the best, was my friend Daniel Okrent.

In 2017. the paper said it no longer needed a Public Editor, and abolished the position. That was a mistake. It was a mistake on its own announced terms. The paper’s publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, said essentially that public voices on Twitter and elsewhere had taken over the job of holding the paper accountable. But subsequent experience showed the paper downplaying or resenting the noise from the outsiders’ claque. In a quasi-valedictory interview with Clare Malone at the New Yorker recently, the current executive editor, Dean Baquet, said, “I could care less about the unnuanced voices on Twitter.”

In light of what has happened since then, the 2017 memo from A.G. Sulzberger on why the paper had moved beyond the need for a Public Editor is piquant. As reported in Politico at the time, the memo said (emphasis added):

“[T]oday, our followers on social media and our readers across the Internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be. Our responsibility is to empower all of those watchdogs, and to listen to them, rather than to channel their voice through a single office.”

As I’ve noted before, going from “empower and listen” to “I could care less” is quite a journey.

And ending the position was a mistake in harming the long-term bond of trust between a paper and its audience. The Public Editor experience was bumpy and imperfect. The incumbents ranged from very good to pretty bad. In some cases they inflamed already stewing tensions within the paper. People on the staff have argued to me that it sounds like a better idea than it turned out to be in practice.

But the lack of a public editor is a real problem. From the outside, it makes the Times seem even more aloof and unaccountable than it inescapably will, given its power and the range of people with an axe to grind about it.

Please, new regime: Do a favor for yourself, and the audience, by looking seriously into re-creating the job, or something like it. The only person who might regret this is whoever ends up in that hot-seat role.

2) Re-examine coverage of 2016 and beyond.

After the aforementioned phony-reporting problem in the early 2000s, known as the Jayson Blair affair, the Times did a thorough internal-accountability review. Among other changes, it came up with the Public Editor role.

Then around the same time, after the Times played its part in spreading credulous reports on Iraq’s supposed WMD threats, the paper did a remarkable public assessment of what it had gotten wrong with its Iraq coverage, and why, and what it could do about it.

In May, 2004, barely a year after the U.S. invaded Iraq, the paper ran a major editorial-page statement titled “The Times and Iraq.” It began (emphasis added):

Over the last year this newspaper has shone the bright light of hindsight on decisions that led the United States into Iraq. We have examined the failings of American and allied intelligence, especially on the issue of Iraq's weapons and possible Iraqi connections to international terrorists. We have studied the allegations of official gullibility and hype. It is past time we turned the same light on ourselves.

In doing so -- reviewing hundreds of articles written during the prelude to war and into the early stages of the occupation -- we found an enormous amount of journalism that we are proud of….

But we have found a number of instances of coverage that was not as rigorous as it should have been…Looking back, we wish we had been more aggressive in re-examining the claims as new evidence emerged -- or failed to emerge.

Responses, followups, expressions of disagreement or support, and other material appeared in the paper in following days. People could differ about this or that aspect of the Times’s internal reckoning. But no one could doubt that it was a brave and serious effort. Bill Keller, executive editor at the time of the review, had earlier come out in favor of the Iraq invasion. He oversaw this report as part of personal and institutional accountability for the role the paper had played.

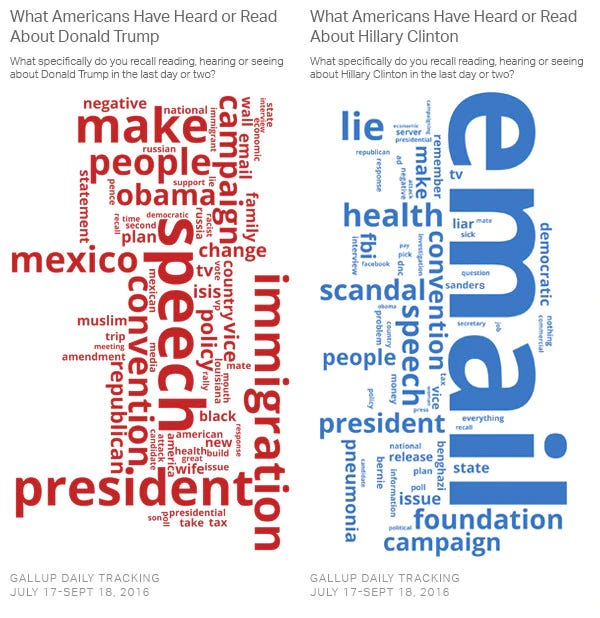

I believe that histories of our era will show that much of our media seriously failed in its coverage of the 2016 election, and the runup to it. In my view—as I chronicled in real-time accounts during that campaign—the Times was an important part of this pattern, especially in grossly over-emphasizing the Hillary Clinton email “scandal.”

I know that I have already mentioned the story below a huge number of times, starting when it appeared. But again it’s worth remembering: the symbol of “but her emails” emphasis will remain this blowout front-page coverage, ten days before the election, of a scandal that evaporated to nothingness.

Why did this matter at the time, and still matter now? Because it illustrated the difficulty of even our very best press institutions in keeping their bearings, and helping the public do so.

I believe there will not be a single historian who, when looking back on the events of 2015 and 2016, will contend that these two things were of comparable importance: (a) Hillary Clinton’s emails being on Anthony Weiner’s cell phone, which was the news peg for the front-page layout above. And (b) Donald Trump’s refusal to release his tax returns; his coterie of soon-to-be-convicted felons, from Paul Manafort to Roger Stone to Michael Flynn; his kow-towing to Russian interests and to Vladimir Putin, including at the Republican convention; his cloud of allegations about sexual abuses; his walking conflict-of-interest in the form of his children’s business; and on down the list.

But coverage boiled down to the idea of “They’re both crooked, it’s all a mess, who are we to judge.” It’s one thing for me to say that about the coverage, and another to see what Gallup discovered about the information voters had received about the candidates in 2016:

Of course, journalists working in real time can’t know how things will turn out, or will look in the future. That’s the definition of our business.

But we can try to keep perspective. And, again, I believe that no future historian will say that the leading American press met the standard of maintaining perspective through the rise of Trump.

Of course I could be wrong on this. But it should matter to the paper’s new leadership to find out and understand. Dean Baquet has said several times that he personally has “no regrets” about the email coverage he oversaw. OK.

But for the institution as a whole, as it starts a new era, the words of 18 years ago still apply:

In imagining the ways that American democracy has reached its current straits, “it is past time we turned the same light on ourselves.”

Welcome and all good wishes to Joseph Kahn!

I am not so sure about the "brave effort" of May 26, 2004. It concludes: "We consider the story of Iraq's weapons, and of the pattern of misinformation, to be unfinished business. And we fully intend to continue aggressive reporting aimed at setting the record straight."

That seems to have been an unkept promise. And not-keeping this promise has led to a New York Times that for four years assured me, several times a week, that Jared and Ivanka were horrified and were working diligently to save us all.

Yours,

Brad DeLong

Very informative piece. The Gallup Hillary Clinton word cloud is unforgettable.

I'm struck by the before-66 expected retirement. You can gain a lot of wisdom at 66+.