We all know what we’re supposed to worry about, when it comes to debate-on-campus, the constraints on free discussion, and also the flow of courageous independent thinkers into the ever more-imperiled American press. Major newspapers remind us every day.

Last month, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I spoke with someone at the center of many of these pressures. She is Raquel Coronell Uribe, originally from Bogota, Colombia, who will soon start her senior year at Harvard and is the first Hispanic person to become president, or editor-in-chief, of the independent student newspaper The Harvard Crimson.

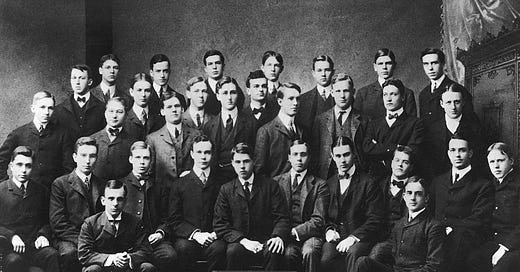

This is a job Franklin D. Roosevelt held some 120 years ago. I’ll let you pick him out among all the other suit-wearing, clean-shaven, prep-school-looking WASP-y men in the photo of the Crimson’s staff in those days, above. (He’s near the middle.)

The paper’s staff looks much different now. But its independence is the same — unlike publications at many campuses, it has no financial, editorial, or other official ties to the university — and so are the pressures on it.

Can “kids these days” handle contention, debate, uncomfortable ideas? Including at the most elite institutions, generally portrayed as hothouses? I had this same job roughly midway between FDR’s class of 1904 and Raquel Coronell Uribe’s class of 2023. In my college class of 1970, internal and external pressures were at least as intense as they are now. Last month in Cambridge, I spoke with Coronell about how people outside elite universities should think about people inside—and particularly their openness to difficult ideas and debate.

The whole discussion is a little over 20 minutes long. You can hear it above—and I hope you will. I’ve also posted a separate item with a full transcript; it is here. For now, here are a few highlights, with time cues linked to the discussion, in hopes they’ll lead you to listen to more.

Excerpts:

-On getting from Bogota to Cambridge. In Colombia both of her parents were prominent journalists:

Raquel Coronell Uribe 01:26

I was born in Bogota, Colombia, and I lived there for until I was 12 or 13.

Although somewhere in the middle, we did an impromptu move to California. Both my parents are journalists. And my dad's work as a journalist at the time when I was around six years old, put a target on his back, and really all of our backs, because, you know, powerful people didn't like the reporting that he was doing and what he was finding.

With the help us Committee to Protect Journalists, and the Knight Foundation, and Stanford, overnight we pretty much packed up our life in a couple of suitcases and flew to San Francisco. And we were in the Bay Area for two years, while things calmed down a little bit.

Long story short, I ended up in Miami afterwards and got the opportunity to come here as a student at Harvard. And it took me a little bit to get to the Crimson. I didn't join until my sophomore year. But I always read the Crimson and I knew that I had to be a part of it. And as soon as I walked through these doors, I just felt the energy of the newsroom — of people bustling to get the paper out, to write their articles, to edit, I knew that this was my new home. So I dove into the paper.

On “kids these days” and their view of a future in journalism

Fallows 06:23

Based on the experience you and your colleagues have had at the paper—day after day, late into the night— what would be your bet for 10 years from now, what proportion of them will be in some form of journalistic activity?

Coronell 06:35

I think the majority of them.

I don't think that we all know exactly what it is we want to do. But I would be shocked if the majority of us, more than half at least, aren't doing journalism in the future,

The way that my dad puts it in, and that I agree with, is that journalism is a little bit like a bug. Once it bites you, it’s like you're done. That's who you are. If you like it, you will be like infected with want to do it in some form or another for the rest of your life.

On “things that can’t be said”:

Fallows 09:47

Is there ever an occasion where people say, Gee, 10 years ago, 20 years ago, I bet our counterparts could have made X or Y or Z argument, but we can't do that now because we're afraid to step on toes. Which is the impression you get from most coverage of elite universities these days. Does that kind of feeling come up?

Coronell 10:08

I'm sure it does for you know, individuals and people here and there, but it's not something that I have ever heard, you know, the board editorial board express or a large group of people in our newspaper express.

And I think actually, the Crimson has served as a venue for people who one might think would feel that way, to have their opinions published. You know, within reason, obviously—we have editorial standards, and we enforce those. But those pieces are published. And I think that goes to show our willingness to engage in debate and to cultivate that debate, and to make sure that it is a part of campus life and a part of journalism's life.

On shifting away from print: The Crimson, which has been a six-day-a-week print newspaper, has just announced that it will switch to one print edition per week—more or less on the model of the NYT’s Sunday sections, or the WSJ’s Weekend Review—plus round-the-clock digital coverage. What was the reasoning?

Coronell 16:43

It's a decision that was not taken lightly at all. And I think that we wanted to make sure that no matter what we did, we would remain, you know, the oldest continuously published college daily, and I think it's just a matter of what form that daily takes.

I think that, you know, my colleagues and I, we, we all see the value of print, and how important it is to kind of have that physical paper to hold in your hands, and both from just a journalistic perspective, and you get to present content in a way that you don't otherwise.

And also just the nostalgia historical value. And I think one of the reasons people joined the Crimson is because of that. So so I guess I'll just preface that discussion with that.

And I think what it came down to was that people really are not reading the print newspaper anymore. When you looked at the pickup rates, it was less than a third of students who were really picking up the papers on a daily basis. Putting together a paper takes the entire day, and then some. And it just was a question of where of how we wanted to engage with our readers and what kind of content we wanted to give them and where to put our sites.

On what others might find surprising about her job:

Fallows 21:24

I’d like to ask you just one other question. What's the main thing that's a reality of your life—including as the first Latina woman to be president of the Harvard Crimson—that you think people don't understand? Or they'd be surprised to know about your daily life here?

Coronell 21:55

Oh, that's a good question. I think people may not know that I more or less live here…

Fallows 22:13

[Laughs] … I know that! I know that!!! Why do you think I was in Adams House? [The Harvard “house” closest to the Crimson’s office.] It's like 20 feet away from the paper.

Uribe 22:19

I wish I was in Adams. And I more or less live here. And I think from from the moment I wake up to the moment I go to bed, I'm doing Crimson work.

There is a lot more to hear. Please give a listen when you can. And think about people from a wide variety of backgrounds, including those with more lucrative options in front of them, who are deciding about journalism: This is who you are.

Share this post