The Importance of the Milley Call

Meeting "jaw-to-jaw" matters, as Winston Churchill put it. Even over the phone.

The scope of this post is U.S.-Chinese military relations. I realize that details of the reported call between the generals in charge of the two forces—Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Li Zuocheng, head of the People’s Liberation Army—are disputed and still emerging, and even when understood will raise other questions. A few first-day assessments I’ve read: from Fred Kaplan, Daniel Drezner, Jennifer Rubin, Lara Seligman and Daniel Lippman.

For now, let’s talk just about the PLA, and why it has mattered that U.S. military officials have tried to maintain personal contacts with its leaders. These contacts—like General Milley’s, with General Li—can make a worsening relationship less volatile.

The real version of an often-bungled Winston Churchill quote is, “Meeting jaw-to-jaw is better than war.” It particularly applies to today’s U.S.-China tensions. Here is why:

An army without combat veterans

The most under-appreciated fact about the Chinese military is that it contains practically no combat veterans.

The PLA commander, General Li Zuocheng, is an exception illustrating the rule. He is in his late 60s and was wounded in action during China’s border war with Vietnam more than 40 years ago. (China’s Vietnam war was much shorter than America’s, and roughly as successful.) As you would expect, very few people who served with him are still in uniform.

Since the 1990s, thousands of PLA troops have served in UN or other peacekeeping missions around the world. In 2016, two of those Chinese soldiers were killed in a firefight in South Sudan. Another was killed in Mali. These were China’s first overseas combat fatalities since its Vietnam war. According to UN statistics, a total of 20 Chinese people have died of all causes while on UN peacekeeping duty. For comparison, Canada has had 123 deaths on these missions, and France 115.

This is service, and sacrifice. But in terms of “normal” or even “irregular” warfare, the all-too-normal status of the 21st-century United States, the PLA has almost no first-hand modern experience. From enlisted people to senior officers, it has few or no battle-seasoned combatants. Its plans have been tried and fine-tuned in war games, as opposed to actual wars.

That China has not been officially at war is hugely preferable to the alternative. Everyone should hope to be able to say the same a generation from now, and a century.

Yet a military without combat experience, no matter how well equipped and rigorously trained, is inevitably different from one shaped—and strengthened, and weakened—by ongoing war. The modern U.S. military has paid a terrible price for what it has learned about people, machines, and concepts under the pressure of sustained combat. In the process it has inflicted incalculable damage as well. The Chinese military—fortunately—has not paid or inflicted those costs.

The reaction we’d hope for, vs. the ones we might get

The cultural and operational outlook you would hope to see, in a war-games-only military, is caution: We’ve never done this before. We don’t know how much we don’t know. Let’s proceed with care.

Another term for this is, the capacity for tragic imagination. What if things don’t go as we planned? What might we regret? Or wish we’d re-thought?

The reaction I most dread, from the Chinese side, is the opposite. It is the paradoxical (but real) combination of arrogance and insecurity that characterizes many “rising powers” and has marked much of China’s dealings with the world in the Xi Jinping era.

-Arrogance: What could go wrong! Let’s teach a lesson to these paper tigers, with their rotting empires. It’s our turn now.

-Insecurity: We have to be on hair-trigger. The enemy is encircling us and could strike at any time.

The encirclement view is long-standing and powerful among China officials. Recently I mentioned that about a dozen years ago, at the Chinese counterpart of West Point, I heard a detailed lecture on how their country was being surrounded by U.S. forces. The illustration below, from a Western think tank, gives the idea. (Though the maps I saw were more lurid, with big red arrows showing possible attack routes into China, and little American-flag icons marking places where U.S. and allied aircraft, ships, or troops could be based.)

Joe Biden did not mention China in yesterday’s announcement of an Australia-U.K.-US alliance to beef up security in the Pacific, but the new nuclear-powered submarines for Australia will immediately be added to PLA maps.

(Why was one of the cradles of the Chinese aviation industry not Beijing or Shanghai or Guangzhou but instead the inland city of Xian? As I wrote in China Airborne, Mao-era planners favored it because of all major industrial centers, it was farthest from the closest border, and presumably hardest for Cold War-era U.S. bombers to destroy. )

The effects of exposure, and of isolation

Over-confidence, plus insecurity, is a bad combination wherever it crops up, from individuals to nation-states. Through China’s pre-Xi Jinping decades of steady opening, normal human contact generally softened both ingredients. When Chinese students and tourists and business people and officials got to see the rest of the world, they realized that it was neither as utterly decadent as they might have heard in the Chinese press, nor as obsessed with the need to “contain China.” (Which most non-Chinese people, most of the time in most locales, spend very little time thinking about.) Other places had goods and bads, like China itself.

Obviously there were exceptions. But 35 years after my own first travel inside China—for a conference of the World Esperanto League, which is a separate story—the overwhelming lesson of my experience is: The more routine exposure that Chinese and non-Chinese people have to one another, the calmer everyone becomes about the relationship.

But the longer Xi Jinping has been in command, the less of this “normalizing” exposure Chinese people have had to foreigners, and vice versa. This week in the New York Times, reporter Li Yuan conveyed the sobering news of tighter and tighter restrictions on teaching English within China. Familiarity with English had been the bridge for many Chinese to the broader world—after Mao’s doomed 1950s effort to promote Esperanto in that role. Estas vera rakonto.

By nature the PLA is more inward-looking than China’s business or academic leaders. China’s civilian organizations have been looking to build markets and contacts beyond their borders; China’s military is in business to protect those borders. Its job is to be worried and suspicious. Thus whatever attitudes fester in isolation, would have further dark blooms within the PLA.

This is where senior officers in the U.S. military, retired and active-duty, have come in.

Surprised but not shocked

A familiar phrase from recent politics is: “Shocked but not surprised.” When I heard about the Milley-Li call, I was, by contrast, surprised but not shocked. I hadn’t known that Milley was in touch with his counterpart. But I was relieved to learn that he was.

Why? Because over the past two decades I have read about, met, and listened to a number of U.S. military leaders who believed that their peace-keeping duties included developing personal relationships with counterparts in the PLA.

At this point I can imagine the Bannonesque retort: We knew it all along! They’re playing both sides! In fact I believe that these officers have been making the United States and the world safer and more secure, by looking for ways to offset the most suspicious, hair-trigger, insecurely-aggressive reactions that might otherwise erupt in a nuclear-armed major world power.

Two scenes—one fictional, one real-life—came to my mind when I first saw reports of the Milley-Li phone call.

One is the classic 1964 movie Fail-Safe, starring Henry Fonda as the U.S. president who makes perhaps the hardest decision in the nation’s history. The movie came out when I was a kid, but my parents wouldn’t let me see it then, because it was so frightening. I had not actually watched it until this spring. To anyone who not seen it recently: Do yourself a favor and watch it soon. (Streaming on Amazon Prime.) It is still terrifying, and you will see its chilling timeliness. It could have been produced with our moment in mind.

I mention Fail-Safe because of one of its central themes is the aggressive paranoia that leaders and nations can develop in isolation, and the needless carnage they can inflict on one another. I’ll leave it at saying: If you watch this film, you too will be relieved rather than annoyed to learn that a U.S. commander would go out his way to tell a Chinese general, “We’re not planning to attack.”

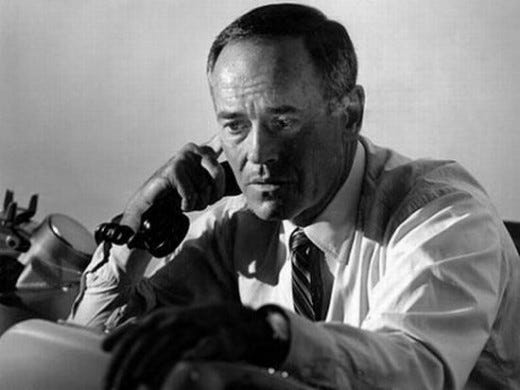

The other episode occurred ten years ago. It was when Mike Mullen, a Navy admiral who was then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, hosted the PLA’s commander, General Chen Bingde, on a tour of the United States. It had been many years since a senior PLA official had been to the U.S. I am not sure whether General Chen himself had ever been here before. That’s a photo of the Mullen-Chen joint appearance at the Pentagon, at the top of this post.

But as I watched TV clips of many events between the two men, and had the chance to be one of a few observers at a dinner Mullen hosted at his official residence, I saw the effect I am talking about. (I wrote about this dinner in China Airborne, and on request can post that excerpt.)

Mullen was subtly but effectively making sure that Chen was exposed to the scale, power, and energy of both civilian and military aspects of U.S. strength. The U.S. was still clawing its way back from the 2008 financial collapse. I was based in Beijing at the time, and saw the portrayals in the Chinese press of the U.S. as in terminal all-fronts decline. Mullen also made sure that civilian and military audiences in the United States heard what Chen had to say, with repeated stress on mutual respect.

A few months later, Mullen paid a return visit to China. This photo is of the two commanders in front of PLA troops in Beijing.

The two leaders’ exposure to each other obviously did not resolve the military, political, economic, and other tensions between the countries. But I am convinced that their ability to speak directly, with some personal and cultural understanding, might have reduced the chances of confrontation through misunderstanding, paranoia, and mistake.

In sum: There is much still to learn and assess about General Milley’s discussions. There is much to worry about on the overall U.S.-China front.

But precisely because of these pressures, and because of the enormous hazards of miscalculation, it’s good rather than bad news that an American commander placed a call to his Chinese counterpart, and that the Chinese general picked up.

Jaw-to-jaw is better than war, even over the phone.

Excellent piece, Jim. I have never forgotten “Fail Safe” and experienced an eerie reminder late inthe afternoon of 9/11. Rounding a corner on a deserted block near W. 43rd St., usually almost as crowded as Times Square, I startled a huge flock of pigeons into flight. Those who watch the movie will know what I felt.

You mention that the Chinese military presently has few combat veterans. Decades ago, I read a piece in The New Yorker, not long after the Sino-Vietnamese border dustup. The author spoke to an unnamed Party official, asking, in effect, “So what was that all about?” The official shrugged and responded, “The PLA needed the practice. They’d forgotten how to fight.”