‘Show Us the Carnage’

A never-ending moral and civic challenge for the media: When real life is horrific, how much horror should we show? Four examples.

The purpose of this post is to re-introduce one of the hardest questions for the press, when dealing with horrific events. The question is how much of the horror to show.

When reality is shockingly brutal, how much of the brutality does the public need to see? Torture? A beheading? The bullet-destroyed bodies of little children? Children abused in other ways?

Is the press properly respecting basic decency by withholding images that, once viewed, can’t be un-seen? Or is it mis-informing the public and mis-serving history by allowing people to avert their eyes?

I don’t think there is a lasting answer beyond “it depends.” Here are some of the things these decisions have depended on. I’ll start with three well-known examples and then apply them to the latest crises. (And for some journalism-world discussion of these issues, see this, this, and this.)

1. Tallahatchie River, Mississippi, 1955.

In 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till, from Chicago, disappeared while visiting relatives in Mississippi. Eventually his body was found in a river. Reportedly Till, who was Black, had whistled at a white woman, which some local white men deemed a capital offense. He was captured, beaten, tortured, shot, and then thrown into a river tied to a 75-pound weight.

When his mother eventually saw his body, she went from grieving to aghast. As a later Washington Post account by DeNeen L. Brown put it:

Emmett Till’s body was swollen beyond recognition. His teeth were missing. His ear was severed. His eye was hanging out. The only thing that identified him was a ring.

The Emmett Till story now is world famous. My focus at the moment is on the also-famous decision by his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. At his funeral she insisted that his casket be open, with his battered self on view. A PBS “American Experience” documentary described what happened:

At a church on the South Side of Chicago, Emmett Till’s mutilated body would be on display for all to see. Fifty thousand people in Chicago saw Emmett Till’s corpse with their own eyes. When the magazine Jet ran photos of the body, black Americans across the country shuddered.

I have seen those photos but am not using them. Mainly that is because I don’t want them to appear unbidden in people’s email. In different contexts—at the funeral, on the pages of Jet, in today’s museums—their power to shock has been intentional and appropriate.

My point here is that Mamie Till-Mobley consciously decided to have people see what racist violence looked like, and nearly all historic assessments have recognized the bravery of her choice.

2. Trang Bang village, Vietnam, 1972.

In the summer of 1972—as George McGovern was sewing up the Democratic nomination for president, and as Richard Nixon’s team was beginning the Watergate plotting that eventually drove him from office—American forces dropped napalm on the Vietnamese village of Trang Bang.

A photo of the consequences, by the AP’s Nick Ut, was on front pages of newspapers around the world. I’m intentionally not using the best-known and most explicit photo from that day. It showed screaming children running in terror toward the camera, as the napalm burned their clothes and skin. They included a naked 9-year-old girl. A different, “milder” photo of the episode is at the top of this post.

That girl eventually moved to Canada, where she had multiple operations to treat her badly burned skin. She is now known as Kim Phuc Phan Thi, and you can see her talking about her experiences with PBS’s Judy Woodruff.

The point here is that in 1972 news organizations around the world made a choice like the one Emmett Till’s mother did. In each case the choice was to make it harder for people to turn away from what their policies could look like on the delivery end. Another famous, gruesome photo from Vietnam by Eddie Adams, of a man being executed with a shot to the head on a public street, had similar effect.

In his book Hiroshima, John Hersey managed to convey with words alone what the world’s first atomic bomb had meant to the people in the blast zone. In these other cases I’m thinking of, images have enormously magnified the power of words.

3. Abu Ghraib prison, Iraq, 2003.

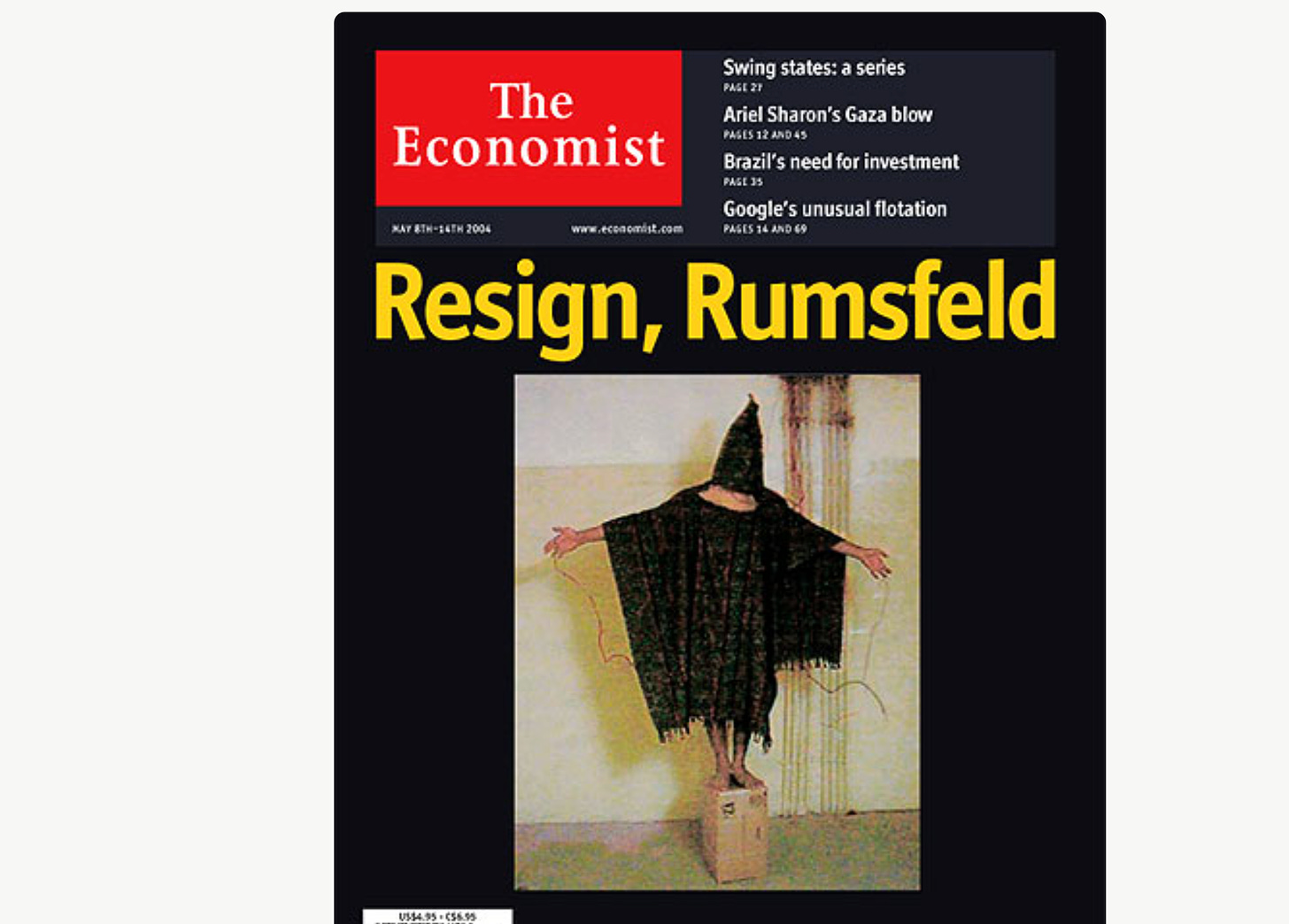

Investigative stories about American abuse and torture at Abu Ghraib might on their own have brought reaction and outrage. But nothing could match the effect of on-scene photos. Their impact was such that The Economist used one of them as its cover:

Without the photos, would the Abu Ghraib revelations have brought a similar response? Would they have stayed as vividly in public memory? (For instance, the permanence of these images is the theme of the recent Paul Schrader movie The Card Counter .) I don’t think they would.

4. Robb Elementary School, Texas, 2022.

After the 19 fourth-graders were shot to death in this latest gun massacre, along with two teachers, news reports said that families had to provide DNA samples, to help identify the bullet-riddled little corpses. For those who know about the AR-15, this comes as a hideous non-surprise. As I described here, the AR-15s used in most mass shootings have bullets designed to inflict exceptional damage. The AR-15’s ammunition was chosen for its “lethality payoff” of not passing cleanly through flesh. Instead the rounds begin to “tumble” when they enter a body and thus increase the harm they do to organs, vessels, brain, bone. Their exit wounds are much larger than the entry wounds.

What we’re seeing from Uvalde is photos of sobbing families, and of “thoughts and prayers” politicians, and of smiling little children in the last few days of their unsuspecting lives.

Should we see the little bodies? The modern counterparts of Emmett Till?

After a gun massacre four years ago, a long-time reader made the case for showing everything. He sent an email that I quoted here:

The media needs to show Americans the truth. Watching tonight's news coverage of the massacre, it was bizarrely possible to think of a mass shooting as a random event like a tornado that causes a community to rally together. Thoughts and prayers for all. Yet entirely missing from the coverage was the truth of what had happened. No pictures of pools of blood. No video of blown out brains. No images of dead children in pews.

Just as the tide of public opinion against the war in Vietnam did not turn until images of the war reached into American living rooms, today's epidemic of mass shootings will not end until Americans see and share in the bloody experience. Scalia's Heller decision will not join Taney's Dred Scott opinion in the ash heap of history until Americans are moved to action by indelible images from mass shootings of suffering and death.

So here is a plea to the media. Do not let decency standards shield us from this indecency. Show us the carnage and do not let Americans look away from what the NRA's lobbying has wrought

The same reader has written again just now:

The cycle is repeating itself again and again and nothing has changed. So again I plead to the media: Show us the carnage. Governor Abbott's rebuke of Beto O'Rourke for alleged incivility would probably look different against a backdrop of bloody dead children as opposed to a community gathering for Thoughts and Prayers. The American people need to see the consequences of our policy choices.

This repeating cycle of mass slaughter will probably not be interrupted until the American people see and experience through the Fourth Estate the bloody realities of gun violence. The concept of lynching can be abstract until you see the battered and bludgeoned face of Emmitt Till.

Today the horrors of Uvalde remain abstract because the obscenity of the slaughter is unseen.

What is the right answer for the media, and the public? I genuinely don’t know. A strong argument against “show us the carnage” is that brutal images would just further brutalize. After all, photos and postcards of lynchings were popular souvenirs a century ago. Images of violence may simply desensitize people—as omnipresent and ever-more-realistic “shooter” video games have surely done. Did worldwide images of two-year-old Alan Kurdi, the Syrian boy whose drowned body washed up on a Turkish shore, really change awareness and action about refugees’ plight? Maybe.

And as for the American parents and family who, in growing number with each new schoolyard shooting, must decide how to remember their lost children: Might they prefer to keep the damage and horror private? And have their beloved child be remembered from the beaming, innocent photos we are seeing now? As opposed to a ruined corpse?

I don’t know. Those of us fortunate enough not to have faced such decisions can’t know. I note that few of the thousands of American families who have undergone this grief have chosen to share morgue-style photos.

Perhaps, unlike Mamie Till-Mobley, they have lost hope that it could make a difference.

Oh so powerful commentary, Jim, I feel shattered just reading the series of horrific events. Yes, I think the carnage should be shown -- to show the truth to the Ted Cruz and Mitch McConnells out there of what they permit to become a part of the American reality.

The videos of George Floyd changed how Americans see police brutality. Without them, it's possible that Derek Chauvin and the other cops would have never been charged.

But I also think that by indiscriminately showing pictures and videos of such horrors, we run the risk of desensitizing people even as we hope to wake them up.

Lately I've been thinking that perhaps if people saw what a child looks like after they've been shot by an assault rifle, none of these pro-gun GOP scum would still be holding political office.