Shanghai Quarantine Diary, Part 4

Carl Setzer went to Shanghai on a business trip. He ended up learning about Covid lockdowns, which are increasing again in China. "Sixteen years, come and gone."

This is the fourth and final installment in Carl Setzer’s diary of his weeks of detention in a Shanghai “Covid hospital.” You can see the previous entries at these links: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

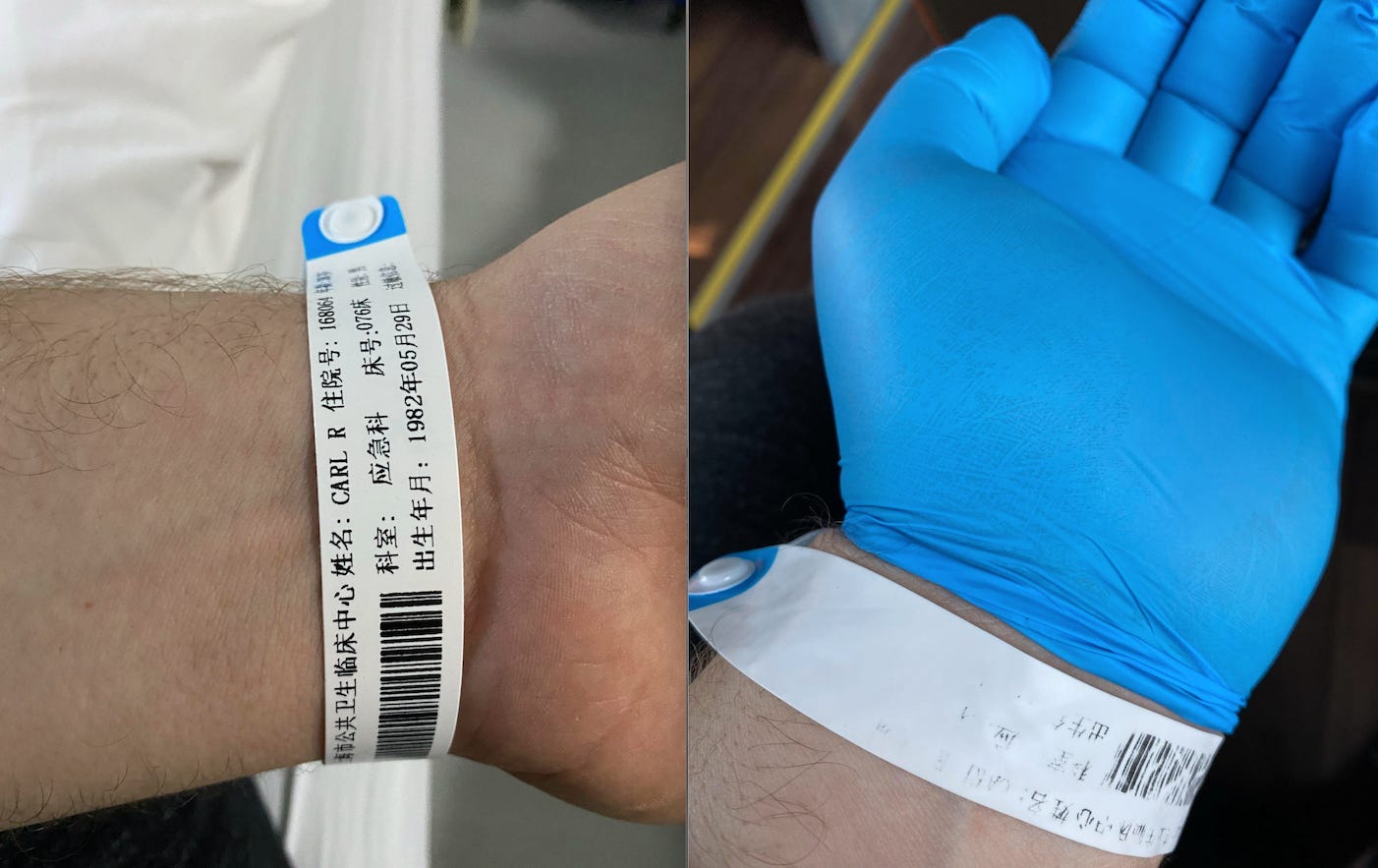

Again as a reminder: Setzer, an American, had lived and worked in China for more than a dozen years, starting in his early 20s. But after a flight from the U.S. in December, 2020, he tested positive for Covid. As a result he was detained for many weeks, against his will, in a Covid facility near Shanghai.

At the end of the previous dispatch, he described his despair at the idea that he could be detained for as long as 120 days, while his wife and two little children were in the U.S.

Covid Quarantine Diary, Part 4

By Carl Setzer

‘The other patient was a man I knew very well even though we had never met.’

The morning after my breakdown, I was awoken at 4:44 a.m. and swabbed. A new early-morning record. I asked the nurse about the nose-washing machine. I was now desperate.

On the 19th day of my detention, the door opened after lunch and two more patients were admitted; confused, angry, and scared. Both of them were Chinese citizens. This was the first time I had been in the room with non foreign-passport-holding patients. One was younger, slightly overweight, and clearly from a wealthier situation than the average Chinese patient I had met during my CT scans and transportation experiences. He was placed next to me in Bed +36, the one formerly occupied by the South African.

The other patient was a man I knew very well even though we had never met. He was in his early 40s with sun-scarred skin and the clothes of a migrant worker. He had one duffel bag that was clearly a knock-off bought outside of a train station in a third-tier Chinese city. He was a worker that I would’ve hired to drive a bread truck for me in the early days of our company, or the No. 3 at a local general contractor. The kind of guy who convinces all the able-bodied men in his village to leave their farms to their wives and move to a city like Beijing or Shanghai to work construction. He would’ve been a security guard at our production facility or the guy on the top bunk on a long-distance sleeper train to western China. He was everyman.

My anxiety spiked. I was nobody to a Japanese businessman or a Russian importer or a South African English teacher, but to a tech-savvy Chinese student and a migrant worker, a foreigner was a curiosity. Curious enough to maybe sneak a photograph and post it on social media.

I immediately put on my hoodie and covered my tattoos and put my beard up in a bun. I tried to be as small and forgettable as possible. These men meant me no harm, but exposure in their own social circles might cause irreparable damage to my company or my employees’ livelihoods. China was entering wartime preparations again in the north to fight a third wave of Covid. My visa was registered in Tianjin and my company HQ was in Beijing. Anything that pushed me into a spotlight would mean even more pressure and anxiety. I was sharing a room with Chinese citizens because China had restricted international visitors to the point that foreigners crossing the border slowed to a trickle.

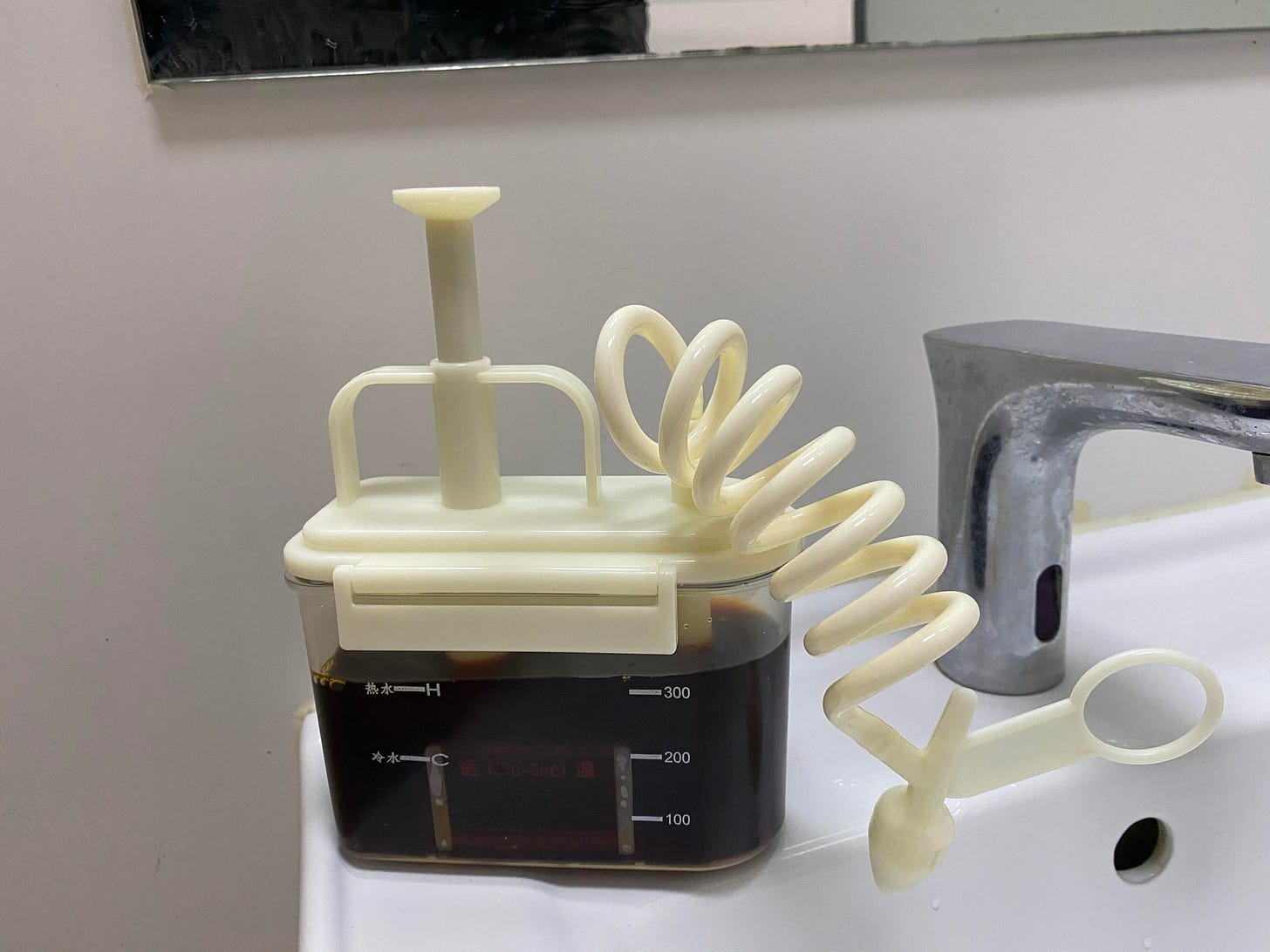

That afternoon, the nurse brought me my nose-washing machine [shown below] and a 300-milliliter bag of diluted iodine. A nose-washing machine is not a neti pot. It’s a hand-pump reservoir with a hose and tapered fitting that goes into your nose and forms a seal with your skin. It pumps the contents of the reservoir up, forcing it into one side of your nose, through your sinuses and out the other side of your nasal passage. It’s incredibly archaic-looking and intimidating. It is described in Chinese as, literally, “Clean Nose Apparatus.”

(If you’re squeamish, you can skip these next few paragraphs.)

The nurse explained how to use it and then watched me show her that I was listening. I don’t know how common nasal flushing with iodine is in other forms of treatment, but I had never heard of it before this moment. I used iodine to sterilize stainless steel and glass instruments for use in analytical labs. I would never have been the first to say, “Iodine? Yeah, that would be a fun thing to force through my nasal cavity and sinuses, 150 mL per side.”

I’ve watched doctors pry off toenails and stitch up wounds and even enjoyed the pain associated with getting tattooed, but this was different. I didn’t believe I needed it, I didn’t deserve it, and the act of doing it was so incredibly painful that it brought me to tears more than once. Of the things that I have ever had to do to myself, this was by far the most painful thing I did more than once. I did it once the first day, then three times a day for the next three days. The hours after were filled with constant irritation and burning while I blew my nose and couldn’t lie down. Literally, rinse, repeat, rinse and repeat again. The college-aged kid, when I got my nose-washing machine, told the nurse he wanted to do that too. After he listened to me do one treatment, he never brought it up again.

The working-class gentleman had tested positive at arrival at the airport and at the triage hospital, but tested negative on Day 1 of his stay at Jin Shan. The college student tested negative on Day 2. They both immediately started asking when they could be released. Their turns to negative while I was forcing iodine into my soul was a contrast that caused a specific kind of darkness to befall me.

‘In China, violence against doctors and medical professionals is often in the news.’

I noticed that the hospital staff, when interacting with my new roommates, were less direct in informing them about the 10-day minimum stay and mandatory 14-day hotel quarantine post-discharge. This wasn’t because they got special treatment; it was because the staff were intimidated by the questions they’d have to answer. In China, violence against doctors and medical professionals is often in the news.

When the two local patients checked in, they reacted the same way I did when I entered the room, only out loud, with volume and tone: “What is this? Why are there other people in this room? Why don’t I get my own room? I’m not sick! This isn’t right! This isn’t fair!”

The two in my room were a case study in economic disparity in contemporary China. The young kid was from a rich family in a second-tier city outside of Shanghai — rich enough to send their son to America to study, but not rich enough to enroll him in even an average school in the first-tier cities of Shanghai or Beijing. The first thing he did was have deliveries sent to the room: food, electronics, clothes, more food, even more food.

The patient from the working class had a cell phone, no headphones, and a small vial of shampoo and bar of soap that he had brought with him from whatever hotel at which he last stayed. He did not have his national ID card with him and could not order anything for himself without the help of the kid or the hospital staff. This man did not suffer from ignorance, he simply lacked expendable income. He was, by all definitions, more lost and disconnected than I was.

The three of us had very little in common. The first couple of days were uncomfortable. They didn’t speak unless I was in the bathroom, showering or brushing my teeth. When I was in the common area, we all kept to ourselves.

‘Stay away from the foreigner. They brought the virus to China.’

The migrant worker’s leader called him on the second day and the topic of a foreigner being in the room was discussed. The leader yelled out, likely not realizing that he was on speaker or that I could understand, “Stay away from that foreigner! They brought the virus to China and you have to protect yourself!” Then the leader put his grandson on the phone, who taught the migrant worker how to say simple English words. It was both insulting and extremely cute and heartwarming. And that about sums up my 16 years of social interactions with strangers in China.

Other than communicating simple things and trying not to eavesdrop, we didn’t actually talk to one another until their fifth day, my Day 24. My previous day’s test was negative, the first time I had tested negative on the CDC standard. Two doctors came in after dinner, told the migrant worker his test reverted to positive, told the college kid he was still negative, and then told the college kid to “tell the foreigner” that he’s positive again too. Both of them looked at me as I took off my headphones and the kid said in Mandarin to me, “You are back to positive.”

While that sunk in, I watched as the doctors tried to leave the room as quickly as possible. I called after them and demanded an explanation. The first time my negative test reverted back to positive I was filled with a wave of sadness, but this time I felt pure anger, not only about the test but the horribly unprofessional delivery of such shit news.

This part might seem strange to people from anywhere else in the world, but PCR tests are very accurate at testing for initial viral load. Out of the current tests available, the PCR test, or genome test, is the best at detecting the DNA protein of a virus. But the problem with PCR tests is they don’t really test for viability or levels of contagion, just the presence of the virus via detection of its viral protein. So, the rest of the world uses the PCR test to detect the virus’s presence and then moves past the test and starts a clock on when symptoms should appear, then when the fever breaks, and uses those physical indicators to determine when levels of contagious activity are concluded. But China uses the PCR tests continuously to detect for the presence of the virus in your nose. Whether the virus is alive or dead doesn’t matter. Depending on cases, the virus can stay in your nose for up to four months — three and a half months after you stop being a threat to society.

‘They started seeing me as an ally. But we didn’t speak candidly again.’

The doctors gave a start before composing themselves and telling me that I should be quiet, I could be here for 120 days, no tests are perfect, it’s my own fault, I’m too fat, I should rest more, drink more water, etc., etc. The same recycled tropes and masquerades of authority. I steadied myself, because getting angrier would have helped no one. They left.

Both the other roommates apologized and told me they couldn’t imagine what I was going through and that this is why they preferred to live anywhere but here. The topics of human rights, personal freedoms, and lack of compassion all came up.

The migrant worker spoke of feeling true happiness in moments of poverty abroad in contrast to the constant shame of inadequacy he experienced in China. The young man spoke of the freedom he felt in America, where people leave you alone. No one cares how you dress or who you date or what career you pursue. I often heard that same enthusiasm from the foreign émigré community in Beijing when speaking about the opportunities and freedoms they felt in China from 2004 through 2013. No expat much says that anymore.

Afterwards, we were all warmer to one another. They started seeing me as an ally. But we didn’t speak candidly again. I can imagine the first time was because we were all temporarily emotional and in need of relief and community. I reverted to keeping to myself, but the looks we exchanged were softer and devoid of anxiety or trepidation. When you are one of three detainees in a room, the realities are human-based, not geopolitical.

On Day 27, my test results came back “weakly positive.” I joked with the doctor and asked her what the difference between a weak positive and a weak negative was. She laughed for the first time in a month and told me it meant I was almost out of here. A definitive statement from a doctor made me feel better than any test result. Tests can be manipulated or poorly administered, but in my situation, when a doctor has the confidence to say something that sounded firm, that meant I was as close as I had ever been to getting out. She responded that if I’m not negative tomorrow, then it should be really, really, really soon.

‘Weak positive again.’

The next day, Day 28, my test came back weak positive again, and both of my roommates were informed that they would be released the day after. The news of their impending departure came at around noon. Both men immediately started packing their luggage and calling friends and family. They would be transported to a hotel for another 14 days of isolation, but for them, like my first two roommates, this was a definitive step toward freedom.

The procedure for checkout was to pack all of your nonessentials the day before. An attendant would come and take these things for sterilization. This was similar to how they sterilized the bedding in preparation for the next guest: your luggage was enclosed in plastic sheeting in the hallway, and the same ozone generator they used for the beds was connected to the plastic. Thirty minutes of pure theater. You were allowed a bag to take with you, which wasn’t ozonized. Because…epidemiology?

After my roommates finished packing, we chatted about the two weeks of hotel quarantine that awaited. The migrant worker laughed and said he hoped the bed was more comfortable. The college student said it was ridiculous and he wished his parents hadn’t pressured him into coming home for Chinese New Year, he might get trapped here in Shanghai and have to find a job. We all laughed because no one was finding a job anywhere in China recently.

After dinner, two administrators came back to give my roommates their checkout documentation and to settle up the bill. Once the clerical admin concluded, a doctor entered to go over their final medical report and to tell me I was negative. I didn’t react. This doctor may not have known that this was my third negative and that I was a little jaded by the idea that I might, maybe, possibly could leave sometime…soonish. I asked if it was weak negative or strong negative. My roommates laughed while she sighed and said there’s no such thing as a weak negative and that I should trust these results. I slept soundly that evening. I was resolute that three negatives regressing back to positives would be absurd.

The final checkout tab: $100 per day.

Day 29. After my roommates were taken away at 10 a.m., an administrator whose voice I didn’t recognize came in and told me that I was on the discharge list and that I would be leaving the next day at 8:50 a.m. I asked if that meant the second CDC negative test had come in from yesterday’s swab. She said she didn’t know, but that she wouldn’t be here if she didn’t have approval from the leader to talk to me about leaving.

I washed and packed my things one last time. The attendant took my excess luggage to be purged. I slept nine hours for the first time in a month. I woke up the next day, folded my clothes, and packed my backpack.

After watching the cleaning lady strip five beds during my stay, I decided I would save her the hassle, and I broke down my bedding and folded it for her and put it on a chair. Halfway through, she came in to do the scheduled mopping and saw that I was doing her work for her. She protested and said I didn’t need to do that. I told her it was nothing, and after a month I was basically on her team now anyway. She thanked me and said I was different and terrific — or “terribly different,” depending on the context you want to read her statement in.

A couple of minutes later, they brought me my checkout invoice and the balance of my deposit in cash. Came out to about a hundred dollars a day, almost to the penny. I signed all of the paperwork and an administrator photographed me taking the envelope and counting the cash, and then photographed the money representing the unused balance of my deposit, the receipt, the bill, and my signature. Minutes later she came back and escorted me out. I asked if I could take a picture of the hallway; she told me there were no photos allowed in the building.

I was given a new box-style mask and blue gloves, then taken to a bus. I put my luggage in the undercarriage while being filmed by a minder. I gave her a thumbs up and she laughed. It’s hard to tell if her filming was meant to intimidate, to record for the official record, or just to archive for her own personal use. There were no doctors to clap me out or any real acknowledgement of the fact that I had been here for 1/428th of my natural life to that point.

Other than my brief exchange with the cleaning lady, there was no feeling of camaraderie at all. Just a large empty 48-seat bus, me seated, on purpose and by regulation, in the back row and the escort in the front row, with the driver at the wheel. A two-hour commute later and I was dropped off at the front door of a heavily guarded quarantine hotel near Pudong Airport. Two more weeks of isolation, followed by a trip to the Exit-Entry Bureau to pay my fine for overstaying my visa (not kidding), and then a 13-hour flight home.

Sixteen years, come and gone. #

For now I will not say more about Carl Setzer’s diary or his current plans in the United States, apart from my respect and admiration for the details and bravery with which he has set down his experience. I’ll also note that the years when my wife, Deb, and I lived in China, between 2006 and 2011, were the era Setzer describes as buoyant and open-seeming. We often reflect on how different those times were.

Thanks to all for reading. Good wishes to Carl Setzer and his family on what comes next.

All my best to Carl Setzer after that terrible month. I hope he has a great life from now on.

Great report and I'm very glad Mr. Setzer is out and healthy, and I think anyone can understand his decision to never go back to China. Those of us in the "hey, China isn't so bad!" camp -- especially those of us who've spent a few years there -- can, I think, recognize that this particular situation brought out the very worst in the Chinese character, especially as it relates to interactions with "foreigners" (a distinction that is made very clearly and definitively by all Chinese). First off, the hospital/dormitory where he was held, though not too far from Shanghai, is really in the outer suburbs, very far from the sophisticated city folk of Shanghai itself. I'm not surprised that the level of English was pretty low if non-existent in an area like that (unlike in Shanghai itself where you'll find the young people in particular, know a fair amount of English even if they haven't had much practice), and I'd also bet the doctors and nurses (who may have had some big-city education) and especially the administrators (who probably haven't had big-city education) there have rarely encountered "foreigners" before. On top of that, you have those doctors/nurses/administrators suddenly dragged into the front lines of a battle with a virus with a lot of politics attached to it -- with origins in China (not terribly far, by Chinese standards, from this area -- let's say a 1.5 hour plane flight, a four hour bullet train ride, a 10 hour normal train ride to Wuhan, by my guess), fast spreading around the world and causing havoc. So I'm just saying that lurking behind this story, and surely putting pressure on all the Chinese Mr. Setzer encountered in this mess, is a government saying: China isn't necessarily the cause of this; but yes, it's a big health crisis; and yes, it has spread to "foreigners"; and we will show how professional we are in dealing with it; and just how technological we can be with our "tests". I'm using a lot of words to say: it's easy for me to imagine the Chinese described here were under a lot of pressure themselves to both play this whole thing down, but also be professional. And they probably had a lot of anxiety about dealing with "foreigners" to this extent, for the first time in their lives. I suspect a diary from one of the nurses in this situation would also be fascinating. Anyway, Mr. Setzer, after obviously seeing the best of China for many years and contributing to it himself in an impressive way, got smacked in the face with the worst of China. I feel for him and I'm glad he's back with his loved ones.