Ralph Nader Looks Ahead, at Age 90. What He Sees Is Not What You'd Expect.

I've known Ralph Nader since the 1960s. In this podcast we talk about his new book ‘The Rebellious CEO,’ which will surprise many people, as it did me.

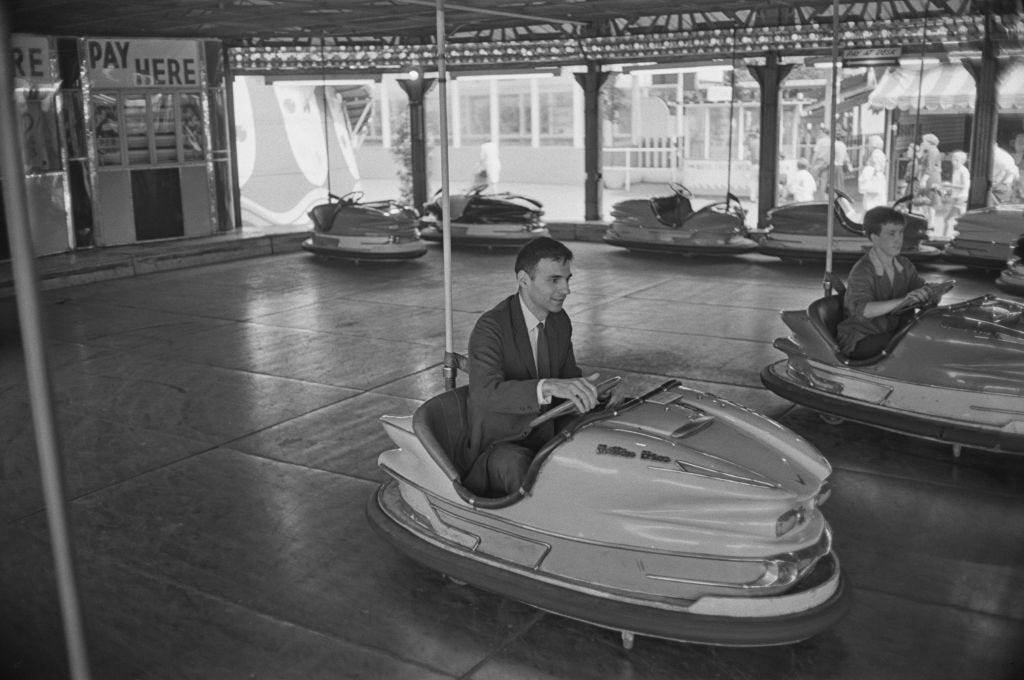

Ralph Nader, then age 32, on a trip to England in 1966 to discuss his internationally best-selling book about auto safety, Unsafe at Any Speed. Naturally the Brit papers wanted a photo of him driving bumper cars, which he did at the Battersea Funfair. (Getty Images.)

In the writing life, it turns out that a lot of your friends are writers. So there is a steady stream of new books by people you know.

Usually a book by a friend or acquaintance “sounds like” that person. People have distinctive styles, voices, themes. Usually it’s good to hear that familiar voice.

Recently I read a new book by someone I have known for decades, Ralph Nader. I met him in the late 1960s, when I was a teenaged undergraduate and he was globally famous in his mid-30s. His best-selling and history-making book Unsafe at Any Speed came out in 1965, when he was 31. In the late 1960s and early 1970s I ended up working on three different projects for him, and writing two books under his auspices.

Before you ask: I know all about Ralph Nader’s role in electoral politics. Anything you could write or say on that theme, I’ve written and said myself, in public and directly to him, at the time and since.

Last week Ralph Nader had a birthday and turned 90 years old. His latest book, presumably not his last, came out shortly before that. Its title is The Rebellious CEO, and it got my attention because its tone and message were a surprising change from what I have and heard from Ralph over the decades. Also because I found it so interesting and valuable to read.

‘12 Leaders Who Did It Right.’

This new book, The Rebellious CEO, consists of 12 brief portraits of leaders from the business world who have used their influence for good. They have done so in environmental policy, and in fair treatment of unions and workers, and in making commerce fairer for the customer, and in exemplifying the idea of enough-ness: That there should be some limit on avarice and accumulation.

The book’s tone, as I say in my initial question to Ralph, is chatty and personal—and the book’s intent is in the spirit of old-fashioned “Exemplary Lives.” That is, what we can learn from people who have decided to buck convention, and why small groups of committed citizens can have an outsized influence.

Some of the people in this book are already well known: John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard (and author of the book Enough), or Herb Kelleher, pioneering leader of Southwest Airlines. Some others I had never heard of before. For instance, Gordon Sherman, a philosophy major from the University of Chicago who ran Midas Muffler. Or Ray Anderson, a carpet-tile entrepreneur from Georgia who set an example of making a corporation carbon-neutral.

I hope you’ll read Ralph’s book. It’s surprisingly heartening and meaningful to have these real-world examples showing: Yes, there can be another way.

Photo from a Life magazine feature on “Nader’s Raiders,” in 1969. Ralph is shown from the back. My partner on a project that summer, Julian Houston, then a law student and later a well-known judge in Boston, is facing the camera at left. I am next to him, at age 19. Our “Raiders” colleagues and future legal eminences Marian Penn and Robert Fellmeth are on the right. (Life magazine, via Pop History Dig.)

In the website version of this dispatch I’ll attach a rough-and-ready, AI-generated transcript of the discussion, errors and all. But here’s why I think the recording itself is worth hearing, even in part. Ralph’s real message all along, in my judgment, is that people should be engaged. They should care about their communities. They should start local businesses. They should know their neighbors. They should realize that they can make a difference—and that energized people are the only thing that ever has made a difference. He says much more at this site, Nader.org.

I ended the interview asking him what comes next, and he has a lot to say. Also, listen to this interview and imagine not knowing the age of the person I’m talking with. See what age you’d guess.

You can download or click on the podcast below to hear my discussion with Ralph.

Podcast recording of interview with Ralph Nader, February 2024. Click to play.

Interview transcript

The transcript below is generated by the recording software I use, Riverside.fm . I haven’t gone through to clean it all up, because mainly I want to direct you to the recording itself.

The subheads, in italics like this, are also auto-generated by Riverside.

—

James Fallows:

Ralph Nader, it is a pleasure to talk with you. We have traveled a lot of roads together. I was realizing that we met back in the 1960s when I was a teenager, and you were in your early 30s and were already internationally famous. Now I am in my 70s and you have just celebrated your 90th birthday. On this occasion, I wanted to ask you about your new book, The Rebellious CEO: 12 leaders who did it right.

Let me just start out by asking this: I was surprised by this book, in a good way. It seemed to me chatty and personal and vulnerable and emotional and positive in ways that people wouldn't necessarily associate with the Ralph Nader brand. Tell me how you think about the tone of this book and the Ralph Nader brand.

Ralph Nader:

Well, over the years, as you know, I've been very critical of the large CEOs of big corporations. And I realized that after a while they defined their own role. There wasn't a frame of reference of best practices by other CEOs who did it right, who met the bottom line, made profit, and decided they were going to treat their workers and consumers well, and the environment, and speak out on public issues of justice. So over the years, I met a number of these CEOs.

Many of them were founders of their companies, like Herb Kelleher, who is the founder of Southwest Airlines, and Anita Roddick, who's the founder of the Body Shop and others. They all had different personalities. Some were extroverts, some were zeroing in on transforming their business to be carbon neutral, like Ray Anderson of Interface Corporation. He's an engineer and a CEO of the largest carpet tile manufacturer in the world.

Characteristics of Rebellious CEOs

But they had very similar characteristics. Number one, they didn't overpay themselves. They want to set an example for their workers.

Number two, they reversed the business model. Instead of saying, well, here's a new way to make a ton of money and we'll make workers and consumers adjust to the maximizing profit. They treated their workers and consumers environment well, sometimes spectacularly like Yves Chouinard of Patagonia, and always paid attention to profits.

Anita Roddick, who's a critical of her cosmetic industry, withering criticisms of what she called the overpriced junk that deceived women especially and harmed them. She was meticulous about designing her shops around the world, starting in England, the United States for maximum profit from which came the money to do the things that she wanted to do. What did she want to do? Change the world, literally. She told her workers, that on company time, pick your social justice cause and work on it. She said, you're not just going to work for a job. Going to work should be exciting, pleasurable, and beyond simply making sales.

And B. Rapoport of American income life, he insisted on his employees forming a union. I mean, unions unheard of in the insurance industry. He not only got them to form a union. He joined it himself.

They also would criticize their own industry they would they would Admit their mistakes publicly Jeno Paulucci would be the first to admit how he screwed up whether he opened restaurants or other things No, I had to close these restaurants because I did it all wrong

It's like they wanted pressure on themselves to make a correction. The other uniform characteristic, Jim, was they hardly ever whined about regulation or taxes. And one reason is they were way ahead of the regulators. I mean, when you talk about Ray Anderson turning his company into carbon neutral, he's way ahead of the EPA. And I need...

Fallows:

And to clarify here, you mean “ahead of the regulators” in a good way—not “one step ahead of the sheriff”? Right?

Nader:

Yes. And when Anita Roddick brought out her business, opened up shops in the US, she went to the FDA for clearance and she started badgering them for how weak their regulation was of the cosmetic industry. They couldn't understand what was going on.

Now, what, what are these all add up to? It adds up to the yardsticks of how to measure the behavior of these giant corporations whose CEOs always justify what they're doing by saying, oh, it's the market. The market just “demands” it. Well, you know, monopolies distort the market, deceptive advertising, subsidies distort the market. There are a lot of things that distort markets and it's an excuse.

And so this book is not just written for the general public to raise their expectations and say to the CEOs of the opiate manufacturers, the oil and gas companies, and the banks, insurance companies, Silicon Valley. We're going to have higher expectations. You're not going to abduct our children into the internet Gulag five to seven hours a day, separating them from their parents and exposing them to terrible ads and other bad stuff, violent programming. No, we're going to have higher expectations because

Higher Expectations for CEOs

Some of these CEOs in the book, the rebellious CEOs, were advocates of peace. They were advocates of arms control. They were advocates of treating children safely and properly and letting them have their childhood instead of manipulating them as if there were so many sales buttons. So it's for the general public.

It's also for business school students. There are millions of business school students who get out of school, they have no way to evaluate the CEOs they're going to go to work for unless they see the best practices such as discussed in this book.

And then it's also for the media. Why is it for the media? Because the media needs to ask better questions of these CEOs running these giant corporations. And they can get the better questions by saying, well, this company CEO made a profit and he did it differently or she did it differently than you. So it helps the media in the way they report on business subjects. So it's for a number of constituents here.

You know, what happened was it struck a chord with Forbes. Imagine Forbes did an interview with me. I mean, you can't add up the times they've denounced me.

We're still waiting for the Wall Street Journal though.

Fallows:

Well, you may have to wait to celebrate your 120th birthday for that …

[Full transcript for subscribers, below. Please note: This is a fairly rough-and-ready AI transcript from Riverside.fm. I mean it as a general guide to the course of discussion; the details are in the audio, which can be played at different speeds. If and as AI transcription becomes better, I can rely on it more. My guess was that this rough guide was better than no written version at all.]