Guest Post: The Part of the Espionage Act That Matters

Jan Lodal, a longtime defense and intelligence official, on a crucial provision that deserves far more attention from press, public, and especially prosecutors than it has received.

Introduction from James Fallows: Jan Lodal has been a friend of mine for decades, and for even longer than that has held responsible positions involving military policy, the intelligence community, nuclear strategy, and similar realms. He has worked for presidents of both parties, starting with his role as a Pentagon aide handling classified data during Lyndon Johnson’s time, and then as a National Security Staff member under Henry Kissinger, in Richard Nixon’s White House. During the Clinton administration he had a senior Pentagon policy role. You get the idea.

In this guest post, Jan Lodal argues that most of the discussion of Donald Trump’s legal culpability is missing a fundamentally important point. As he explains, the Espionage Act of 1917, which is “still the primary statute governing our system of security for government secrets,” has six subparagraphs. And one of them, subparagraph (d), makes the issues surrounding Trump much starker and less subjective, both legally and politically, than they have come to seem.

Why am I posting this? Because I’ve come to trust Jan Lodal’s advice and judgment over the decades in my own writings about the military and about political accountability, and because it’s a perspective I have not seen highlighted so clearly elsewhere. I encourage comment and response.

Here is his case:

No Return: Trump’s Most Obvious Crime

By Jan Lodal

(Jan Lodal is Distinguished Fellow and Former President of The Atlantic Council, and Former Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, Policy. His email address is lodalopinions@gmail.com. )

Discussion of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago papers has made the case seem complicated—legally, politically, and in terms of national security.

But one little-discussed aspect of the Espionage Act of 1917 is clear and unambiguous. I say this as someone who has spent much of his career dealing with the arcana of classified information.

If prosecutors simply focus on subparagraph (d) of the act, their case becomes clear and simple, and Trump’s violation is beyond all reasonable dispute. Let me explain the background of this clause, and why focus on it should allow us to move past the lamentable “special master” ruling and all its consequent and likely intended delay.

Now, the background:

The structure of the Espionage Act.

The Espionage Act is not the only point of investigation of documents in Donald Trump’s possession, or only possible crime. Widespread reporting confirms that some of these documents had the highest “SCI” (Sensitive Compartmented Information) or “SAP” (Special Access Program) markings. Others apparently contained nuclear weapons “Restricted Data,” covered by separate laws and extremely tightly guarded. Trump’s mishandling and wanton carelessness with these documents is totally unprecedented.

But the Espionage Act of 1917 is still the primary statute governing our system of security for government secrets. This Act was already “old” when the current document classification system was put in place during World War II. Convictions under it have often been difficult to obtain, for reasons I’ll explain. Other than the Presidential Records Act, which has no criminal penalties, the Espionage Act is the main focus of investigations related to Mar-A-Lago.

The Espionage Act has six subparagraphs. The first three, subparagraphs (a), (b), and (c), require proof that the perpetrator improperly took or kept “information respecting the national defense” (in today’s law, “classified information”) “with intent or reason to believe that the information is to be used to the injury of the United States, or to the advantage of any foreign nation.” In oversimplified words, this means that to be convicted the perpetrator has to be proved to have been a traitor or a spy. No twelve person jury would unanimously convict Trump of being either a traitor or a spy.

Another provision, subparagraph (e) applies only to persons “having unauthorized possession” of “information respecting the national defense.” As president, Trump clearly had “authorized possession” of all documents containing national defense information related to defense, and ex-presidents have often been kept up to date with classified briefings after they leave office. Thus at least one juror could probably be convinced that Trump had “authorized possession” of the relevant “information related to the national defense”, making this subparagraph not applicable.

And the final Subparagraph (f) requires proving both “gross negligence,” always difficult, and that the perpetrator not only mishandled documents but also “failed to report” the mishandling to his “superior officer.” No one was “superior” to the President of the United States, so his behavior couldn’t meet this test.

The importance of subparagraph (d).

But there is one remaining subparagraph of the Espionage Act that is unambiguously applicable to what Trump has done — subparagraph (d). This paragraph makes a straightforward action a crime: namely, failing to return classified documents if properly directed to give them back. No proof of the level of classification, or the intentions of the document holder, or the content of the documents, is required. Just a simple question, did he or she give them back or not.

The only subjective or “soft” element of proof required by this paragraph is one easily met at trial. That is whether the perpetrator believed the information in the boxes “could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation.” Even Trump had to believe that: it’s true by definition of any document that has been classified. You cannot classify a document otherwise.

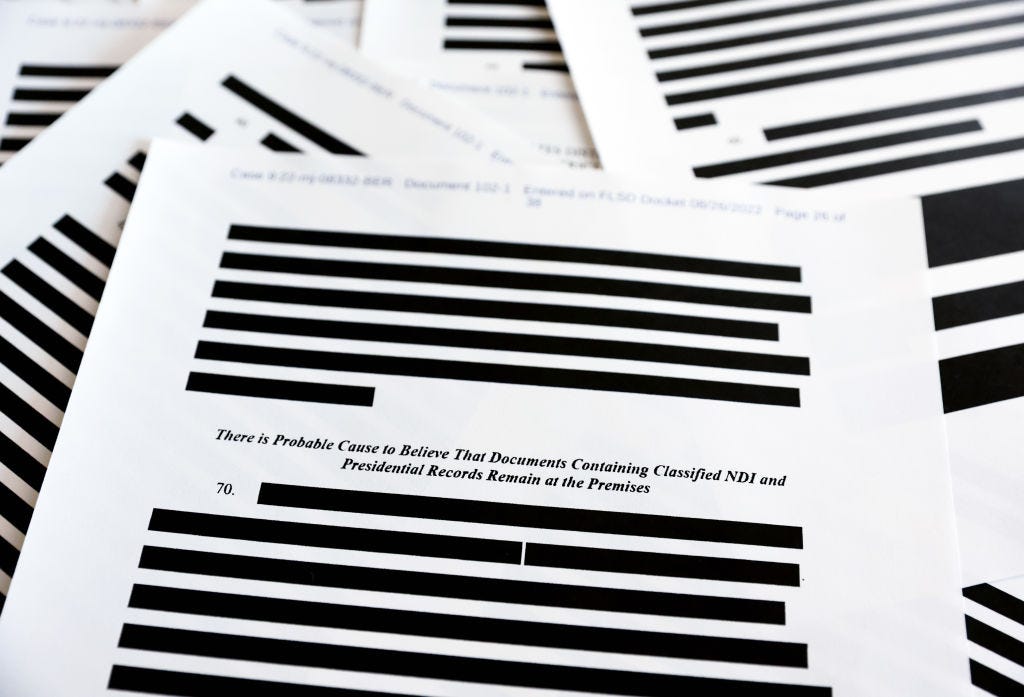

This section of the Espionage Act does not require that prosecutors access or cite individual documents to prove the crime. It requires only that there were any classified documents in the boxes that Trump did not return. On that there is no doubt. It was settled by the release of the Department of Justice (DoJ) Affidavit authorizing the Mar-A-Lago document seizure.

Trump was asked seven times to give the Mar-A-Lago documents back and did not comply, despite the clear requirement of this section of the Espionage Act. The first request came from the National Archives, citing the Presidential Records Act. They made three formal demands the he give them back. Then the Department of Justice intervened and asked three more times but didn’t get them back. Finally DoJ got a court subpoena ordering that he give them back, but he didn’t. So the FBI had to forcibly take them.

Trump’s violation of this Subparagraph (d) of the Espionage Act could not be clearer. Unlike all other crimes being considered for prosecution, Subsection (d) requires no probing of intent or consequence. It defines as criminal a clear process violation -- “failing to return” classified documents when properly asked to do so. Proving this does not require opening up the boxes being re-analysed by the Special Master or even determining the extent of what he kept. The boxes have already been declared by authorities to contain classified information, which is all that must be proved to be covered by Subsection (d). The boxes can remain closed for the trial, so even the attorneys and others in attendance do not need security clearances. The testimony of the agents who reviewed them after they were seized should be adequate.

There is much at stake to hold Trump legally responsible. But to do so will require avoiding the use of those elements of the law that could give any pro-Trump jurors an excuse to vote for acquittal. The risk that this could happen is much greater if the crime asserted is defined by a “soft” standard requiring a subjective judgment on the state of mind or intentions of the perpetrator. These are important elements found throughout the other sections of the Espionage Act, but are very limited in Subsection (d).

The problem with ‘soft’ standards, and the difference between what is damaging and what can be prosecuted.

I have personal experience with how “soft standards” can block enforcement in cases brought under the Espionage Act, even when the offense was extraordinarily damaging to U.S. national security. I served in a senior Pentagon position under President Bill Clinton with responsibility for nuclear and arms control policy—a position I had previously held in the White House under Presidents Nixon and Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. It came to my attention that a journalist had published a story that destroyed a communications intelligence system that gave us direct access to conversations of the highest Soviet leaders.

The journalist’s action was explicitly criminalized by 18 U.S. Code § 798, the “Communications Intelligence Protection Act.” This statute grew out of the increasing importance of what was once called “wiretapping”—intercepting telephone communications. The Act includes restrictions not found in the Espionage Act, including prohibiting “publishing” “communications intelligence. But the leadership of the Department of Justice assessed that First Amendment rights made this unconstitutional, despite the severe damage to national security the publication had done.

The same journalist was later emboldened to publish another “leak”—the details of a spectacular U.S. intelligence success that had uncovered the supply chain used by Iran in its pursuit of a nuclear weapon. This intelligence facilitated a program to disrupt Iran’s nuclear weapons program’s supply chain. Doing so might well have convinced the Iranian leadership that their nuclear weapons program could never be successful, so they should abandon it and join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Stopping the Iranian nuclear threat would have significantly reduced the nuclear risk that threatens all humanity.

No criminal investigation was undertaken in either of these incidents, so it would be improper to identify the individuals involved. But these incidents, caused serious damage to the Nation’s security, demonstrate the difficulty of bringing criminal cases under the Espionage Act unless the crime is spying or direct assistance to a foreign power. And in these cases, the “process crimes” defined by Subsection (d) were not applicable. So serious harm went unpunished.

Since our democracy relies on the public being able to know what its government is doing, punishing disclosure of government activities is only called for when a greater national interest demands it. Any individual being punished needs to have clearly crossed a line between carrying out his or her legitimate duties and harming our national security or aiding a foreign power.

These potentially conflicting imperatives have placed great stress on defining when an action under the direct control of our president can be considered “criminal.” Although the president is responsible for enforcing federal criminal laws, he or she is subject to them like any other citizen.

The president is also responsible for the nation’s security against foreign threats. This security relies on enforcement of the Espionage Act, even if it requires accusing a former president of a crime—an extreme step. These conflicts have resulted in difficulties in the past and they are now impeding efforts to hold former president Trump accountable—even though his actions explicitly violate subsection (d) and may also violate other sections of the Espionage Act. He has also unambiguously violated the White House Records Act, which requires him to submit records of his presidency to the National Archives.

Prosecuting on ‘process,’ not on ‘intent.’

Donald Trump is not the first president to face these conflicts, even in recent times. President Nixon falsely asserted that national security considerations justified his criminality. An email scandal under former President Ronald Reagan led to the conviction of two of his senior aides, John Poindexter and Oliver North, for destroying public records by deleting hundreds of emails related to the Iran-Contra affair. President Reagan apologized for the scandal.

Poindexter’s and North’s conviction was a rare success for the Department of Justice in this area of law. The more common outcome, as in the cases I have alluded to, has been to drop the matter and just move forward.

But the Poindexter/North conviction can provide a lesson for our current situation. The more difficult elements of the Espionage Act were not involved; what was prosecuted was a “process” crime, not a classic “espionage” crime. Prosecutors did not have to establish that the perpetrators had “reason to believe” that their acts could harm the nation. No proof of a certain “belief” or “state of mind” or other subjective criterion was required to convict them. They didn’t return documents and records when required to. QED.

The current situation is similar -- it also concerns a high ranking official, this time the very highest ranking, who violated a clear provision of law and knew he was doing so. He can be immediately prosecuted for a felony, without having to wait for the Special Master’s report or having to prove ambiguous “soft” elements of crimes.

Given our politics and our jury system, keeping the legal actions against Trump simple is better for now. Prosecution for other offenses after getting an initial conviction will then be more likely to succeed. DOJ should take this path to reduce the risk that obfuscation and assertions of inapplicable rights and privileges by a former president could override the fragile rule of law in our constitutional democracy.

#

From James Fallows again: I am grateful to Jan Lodal for spelling out the issues so clearly. Again I encourage comments and responses in this space. You can reach him directly at lodalopinions@gmail.com.

As an extra discussion point:

Jan Lodal's essay goes into some ways that leaks to journalists might be covered in various subparagraphs of the Espionage Act.

This excellent American Scholar essay from ten years ago, by my friend and colleague Lincoln Caplan, goes in great detail into this "leaks vs espionage" point. Its argument is of course not directly connected to the Donald Trump case, but I highly recommend it on the larger issues. It is here:

https://theamericanscholar.org/leaks-and-consequences/

An overly simple summary: Linc Caplan goes into the tangled history of the Espionage Act itself, and argues that he thinks it would be a major mistake to bring interactions with journalists under its provisions. (In his essay, Jan Lodal mentions some leaks to and interactions with journalists, which he says were damaging in intelligence terms but were never prosecuted.)

Check it out.

Thanks to many readers who have already written in with responses. Keep them coming!

I have addressed a few of them that are within the realm of "things I sort of know about." I have invited Jan Lodal to respond on points directly about his Espionage Act arguments.

FOR INSTANCE, here is a reply I received directly from a longtime Congressional staffer, with extensive defense-policy experience. He quotes this part of Jan Lodal's argument:

>>And the final Subparagraph (f) requires proving both “gross negligence,” always difficult, and that the perpetrator not only mishandled documents but also “failed to report” the mishandling to his “superior officer.” No one was “superior” to the President of the United States, so his behavior couldn’t meet this test. <<

And responds this way:

>>Not necessarily. Beginning 20 January 2021 at noon, Trump became a private citizen and superior to no one in the national security structure. All actions after that date would be culpable under subparagraph (f). And based on what we already know about the lax security and comings and goings of foreign nationals at Mar a Lago, gross negligence could be provable.<<

I'm adding this as part of the discussion. Thanks to all.