Guest Post: Kiev in the 1970s, and Kyiv Now

I asked a veteran Russia hand, ‘What would you do, if you were Secretary of State.’ Here is his answer. He happens to be my brother.

The post below is by my brother, Thomas S. Fallows. He has spent much of his life working in and thinking about Russia and its environs. He has lived in Russia several times; he is a Russian speaker and has a PhD in Russian history from Harvard; and he has worked for decades around the world, including multi-year postings in Italy, France, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Saudi Arabia. He now lives in New York.

I asked Tom how he makes sense of the latest tragic news from Ukraine, and what he would do differently if he had a say in U.S. policy. What would he be thinking, announcing, or planning if he were Secretary of State?

Tom responded with this note, which I found clarifying, useful, and absorbing. It came in the form of an email rather than a formal “essay,” so apologies from both of us in advance for any loose ends. Its meaning and points are clear.

The first part is his impressions of a Soviet-era Kiev, when Tom was there as a college student in the early 1970s. He writes the city’s name Kiev because that was the universal Russian-style form in those days. I include this part not just because of obvious family interest to me—I had not known these stories—but also because it is evocative about that region at that time.

The second part is about what the United States and its allies can and cannot do to protect the people of Ukraine and to offset Putin. To people who know the region as well as Tom does, his points and emphases may be familiar. To me they are valuable in providing a way to think about what has happened, and what comes next.

I turn the floor over to Tom.

‘If I Were Secretary of State’: Thinking about Ukraine, Then and Now

By Thomas S. Fallows

1. In Kiev, 1973

I was first in Kiev in a really marvelous, miraculous time in my life. I was in Leningrad, USSR, on my undergraduate 'junior year abroad' in my case Inside the Iron Curtain.

Flying to Leningrad through Warsaw in 1973, I really felt shocked by the old 1956-60 type of Stalinist soldiers on guard at the Warsaw Airport. Coming into Leningrad, it was as if I were going Behind Enemy Lines. Very poor and depressing, very under-developed, very dirty and disorganized and rustic, very Russia.

Gera was my closest friend there, he was my roommate in 1973 and his job was to spy on me. As a 19-21 year old roommate, obviously he was not good at his job and we discussed frequently as to what Summary Comments he should write on his weekly KGB report on roommate Tovarish Fallows.

Our 1973 group was sponsored (on a US college consortium basis) by the University of Washington (state)…. We had a field trip from Leningrad to Kiev. I absolutely loved the Pecherskaia Lavra, the old monastery dating back to the mid-900s. [See photo above.] It was spooky, going up and down the tiny staircases in the Monastery, to see old mummified and waxed skeletal hands and faces of centuries-old Russian/Ukrainian monks who died in that monastery over the last 1000 years. Coffins in little cubby-holes along the staircases, with orange waxen hands sticking out of the coffins.

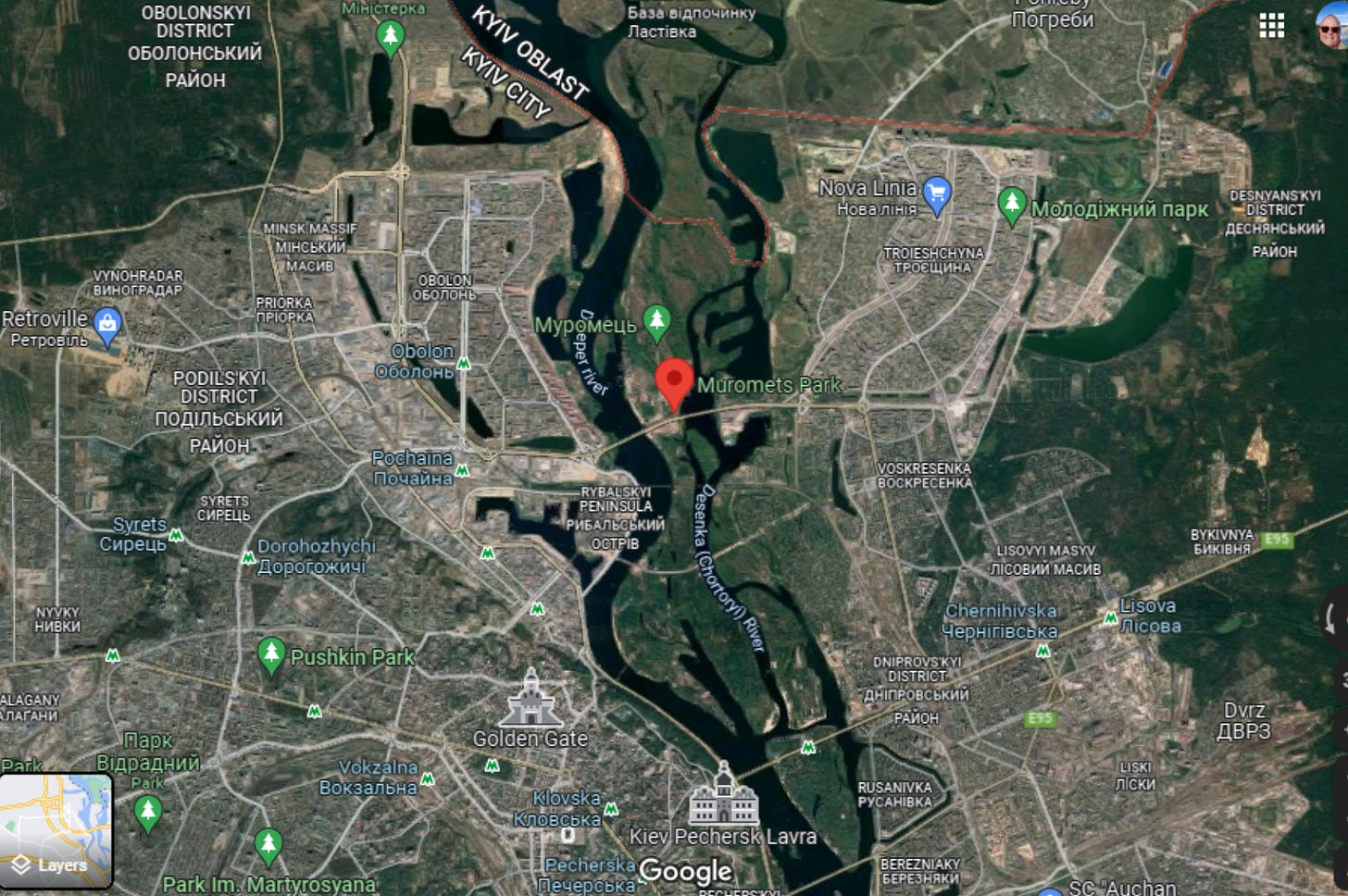

That night in Kiev (this was our rebellious outing away from Leningrad), the three of us (Gera, another US exchange student, and I) got on some bus and went to the Dnepr River. It was about 10 or 11 pm. Obviously what we were doing was illegal. And it could be a security risk for Soviet guards watching the bridge where we were, maybe on the other side of the Dnepr.

In my distant memory of 1973, I still think of that night as one of the most magical things I've ever experienced in my life. Why? The moonlight over the river, the tense fright as to whether a Soviet guard would find us or start to shoot, the encouragement by my friend Gera as to how to behave as per his instructions, and the whole mystery of being "out on our own" in Soviet life.

And the Dnepr was beautiful. It was dark, we were on some form of boat. A rowboat? We went down the River (this is now around midnight after we climbed down the bridge and sequestered a small boat in the middle of the night) and drifted to a small island. I recall walking in utter joy looking at the trees on this small island and the reflection of the moon in the midnight showing on the river. The island was very small, not well wooded, hence little sight protection in case a Soviet guard came by.

So I remember imploring Gera to decide if we should turn around, to know what to do about the risk of being caught. He guided us, we found another wooden boat on the island. There was an old Muzhik, a ragged Russian/Ukrainian maybe 40-50 years old who looked 80 years. He drove us on that 2nd boat, from the island back to the shore. We wound up on the western side of the Dnepr. Ready to head back to the tourist hotel where we were on this outing organized by the Leningrad student organization. It was maybe 2 or 3 am when we returned to the hotel. I was 20 years old.

2. Thinking about Ukraine and Russia

The two countries overlap so much throughout the centuries. The Slavic dynastic in that area began as the Vikings, coming down the Baltic and east of that, to access the Russian rivers which eventually went down to the Black Sea and Central Asia. The Viking river-based trade through Eastern Europe fed into the Silk Road, and became more and less important to global trade as the alternative route to the East (Venice, the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Turkey, on to Asia) was closed due to the rise of the Islam Empire in the 700-800s.

The Vikings settled first in Novgorod, then in Kiev. 8th-9th centuries. "Kievan Rus" was the force converting to Christianity and dominating the region for centuries. Then began the period of Mongol Horde invasions (13-14th centuries), after which time Ukraine was habitually divided between Russia, Poland/Lithuania, and Austrian Habsburg Empire.

There are some important regional splits within Ukraine. The "truly Russian' side of the territory, are Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. Crimea is the port town Sevastopol (for the Russian navy, Sevastopol is like San Diego for the US Navy) which is sentimental to Russian hearts since the Crimean War of the mid-1850s.

When I was at Harvard in the 1970s and working at the Russian Research Center, I had a few interactions with the 'other team' of scholars in the region: the Ukrainian Research Institute, where a bunch of very elderly Ukrainian specialists gathered. The star of the show was Professor Olemljan Pritsak, a world-renowned specialist on Old Kiev, who could cite exotic languages showing the influence of Tatar and Mongol phrases on old Slavic.

Given my focus on Russia-only studies, I was surprised by how much the Ukrainian guys spoke about non-Russian topics: especially Lithuania and the Polish/Lithuanian alliance and the Uniate Church (the only Catholic Church for Slavs), and other things non-Russian. They really are a different country, I came to realize.

L'vov (now called L'viv) and other parts of Western Ukraine never really had anything to do with Russia. Meanwhile, for my studies on the Russian Revolution, towns like Kharkov were very important (as this was the center of the Russian mining industry, with a large and militant Russian working class movement). (This is the Donbass area, where the two 'breakaway provinces are located). But besides Donbass, the rest of Ukraine has been separate. Ukraine right after World War I was totally separate from Russia (as a German protectorate until the war ended). Brest-Litovsk also created a big demarcation between Russia and the lands to the West and South. Lenin and Stalin then consolidated Ukraine into the USSR after the Civil War was over, but the separate traditions remained.

One of the most tragic parts of Ukrainian history at the hands of Russia, happened in the 1930s. The Famine. Caused by Stalin and incredibly brutal collectivization policies taking grain at gunpoint from Ukrainian villages, leaving practically nothing left for the population after the grain requisition forces were finished. Millions died from the Famine. (Read Anne Applebaum, "Red Famine. Stalin's War on Ukraine".) What Putin is doing now is only a more brutal and sudden version of what Stalin did before him.

So Ukraine is, and is not, a part of Russia. The two overlap but are also different. Putin is totally wrong claiming that Ukraine has no separate history.

3. How I see the military/geopolitical situation today

The easy 'offramp' for Putin would be to find some pretext FINALLY to stop his aggression, Declaring Victory and returning back to Moscow in triumph. Solidifying Russian control of Crimea and Donbas are the easy conclusions to this tragedy. I believe that eventually, the wise people of the West will have to convince Zelensky of Ukraine to surrender once and for all Crimea and Donbas. They are not 'worth it' to remain in Ukraine. Russia controls them, and Ukraine should formally acknowledge this to gain the Peace. This is a 'cheap gift' from the West/Ukraine to Russia, and it would help Vladimir save face and declare Victory and go home.

But we are caught up in this Ukraine/Western point about "territorial integrity" and "sacred integrity of the sovereign nation". Which means Zelensky cannot make a concession on Crimea/Donbass.

My big surprise here has been the change in outlook and behavior by my friend Vladimir. Over the last 2 decades, people in Asia and the Middle East would frequently ask my opinion of Putin. I always replied that from the Russian point of view, he was a Velikii Russkii Patriot, a great patriot, hero to his country, follower of Peter the Great. But he also seemed strongly dedicated to careful chessmaking analysis and risk analysis, avoiding bad outcomes and rationally considering the terrain.

So through the November-December-January 2021-22 buildup of Russian forces outside Ukraine, it seemed clear to me that Putin's buildup could only be a bluff. Certainly Vladimir would never rationally do this. "If he wanted to take Kiev, he should have done it quickly in November when we weren't prepared...why is he taking so long?"

Then to my surprise, and also to the surprise of many other observers, Putin actually took the crazy plunge last week. Why?? It is obvious that eventually he would fail to keep Ukraine (he could not occupy Ukraine for years under Russian dominance, eventually Ukraine would come back as a separate force). And there is no way he could resurrect the Warsaw Pact. So why is he risking so much for his country when there is no chance for an ultimate victory and the war rational is already very weak. Why?

What drives him, I think clearly, is his resentment of the post-1991 breakup of the USSR and desire to return back to the Status Quo Ante. Anger, resentment, humiliation. They can be powerful emotions, but up until now, Vladimir's reasoning held back his emotions. Now he lost it.

My only explanation is, "Vladimir has lost his marbles". He is so isolated. I look at the huge tables and the amazingly long distances between Putin's tables and the people he meets. He's been very isolated over the last 2 years of Covid. He seems to have become so blinded by power that he could no longer be the rational player he used to be. Now he's gone off the charts. And he does not know how to stop. How to stop him?

I am a big proponent of the sanctions applied, especially the banking one. I've been rooting of a shutdown of SWIFT so am glad to see that. The big step was the series of sanctions on the Russian Central Bank, especially the freezing of foreign currencies held by Russia in Western banks. That was a huge blow and I think it will eventually bite.

But given the way Putin is now shifting toward a strategy he applied so clearly in Chechnya and Syria ("bombard every building in the city, so that eventually it is all destroyed") which Russia showed in the cases of Gory in Chechnya and Aleppo in Syria.

4. What I would do if I were Secretary of State

I give Biden high marks for how he has handled the situation from November onward. My view is that Putin perceived a weakness in the resolve of the West (correctly, in my view), especially after Trump's and Biden's exit plans for Afghanistan. So his resentment and anger about the post-1991 situation had been festering for a long time, and finally percolated in the autumn of 2021 as he perceived "his chance". Go beyond the 2014 excursion, now take the whole country.

The surprise has been that Biden and Europe did NOT back off, and instead strengthened their resolve for unity and resistance to Russia. So Putin wound up with resistance he had not counted on back in the autumn.

What to do today? My vote is to go one step further, and sanction the sale/purchase of Russian oil and gas. Just like Iran and Venezuela.

Extra oil and gas production from other countries can compensate for the withdrawal of Russian product. Germany's gas supply is at risk. But measures have been prepared to offset the withdrawal of Russian gas by supplying LPG deliveries from the Middle East and North America. Fareed Zakaria has been a proponent of this idea and I support it.

One commentator today said "no, I would hold off on the energy embargo, we want to keep that one for reserve leverage". I don't see what further reserve we need, as Putin has already done the maximum of violence short of using his nuclear bombs (and I don't think he will use nuclear weapons, as that is tantamount to an attack on NATO which neither side wish to see.)

To sanction oil & gas sales, the challenge is to balance on the US Average Joe priority sheet: do what we really need to do to attack Putin (now take the extra step and sanction oil/gas sales), or do we protect the US price level of domestic gasoline in order to reduce sufferings by the American public?

I would go for the shutdown of Russian oil/gas, but I am not facing the Midterms in 2022.

Many thanks or this review. As it happened, I was in the USSR on a student trip about the same time (1971) and met some Ukrainian students who made it very clear that they were NOT Russian. Regarding the present inflation and possible energy sanctions, one problem I've not seen discussed anywhere is that the Biden administration has punted on the task of educating the American public regarding how inflation increases happen rather naturally during times of disruption; and how prices also come down. The news media are pretty useless regarding this problem, so the general public is stuck with remotes of TV reporters in front of daily gas price signs at service stations.

Interesting history and well-informed analysis of where best to go from here. Thank you!