Grace Under Pressure: Another Example from the Skies.

This post is not about the horrific news of the moment from Gaza. It is intentionally on another theme: an illustration of people doing their jobs with remarkable competence and calm.

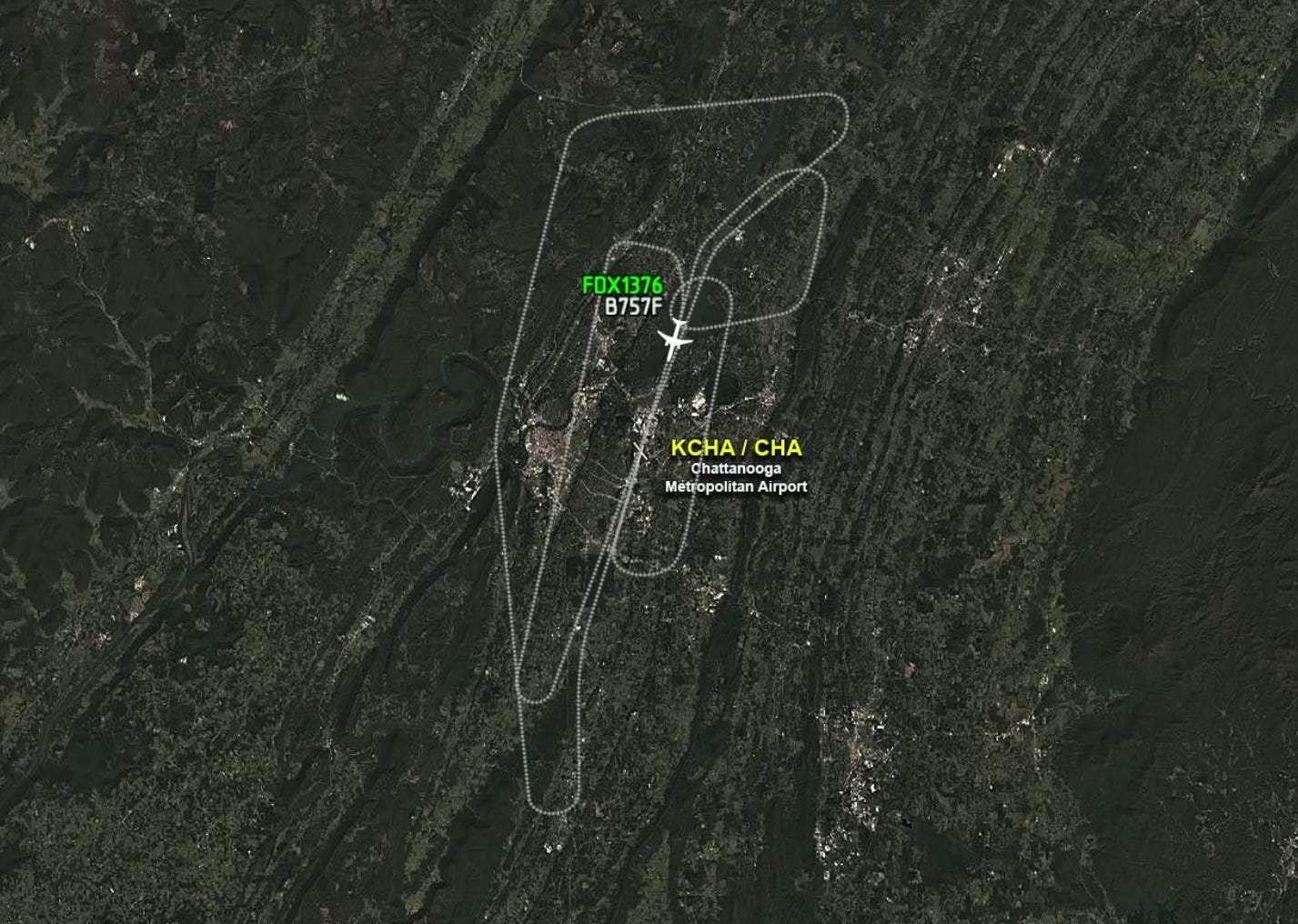

Soon after takeoff from the main Chattanooga airport this past Wednesday, a Boeing 757 flown by FedEx had an equipment failure. The plot above shows the course on which an air traffic controller guided the plane to a dramatic but safe landing. The audio captures the way any of us would hope to sound under pressure and with lives on the line. (Screen image from RealATC on YouTube.)

I wrote this post two days ago and was just about to hit “publish” when news broke of the Hamas terror slaughter in Gaza. Even as that news unfolds and darkens, I’m going ahead and posting this—not as a distraction or counter to gruesome world news but as a reminder of another side of human cooperative potential.

The original point of the post was simply to direct anyone interested in aviation safety, and more generally in collaborative cultures and how people can excel under pressure, to an extraordinary recent event in the skies over Chattanooga, Tennessee. I think there is still value in doing so.

The event is captured and recreated in a 17-minute YouTube video from the RealATC channel. That’s a long time, but I found that when I started watching I was engrossed. I embed the whole thing below and will first summarize the story. (Also note that the video condenses action that stretched over more than an hour. The time references below are all to the video rather than to real flight time.)

What happened: A Boeing 757 flown by FedEx, carrying FedEx cargo and a flight crew of three, took off late last Wednesday night from Chattanooga’s main airport. It planned to make the short trip to the main FedEx hub in Memphis, on the western edge of the state. FedEx sends several hundred flights to Memphis each night, getting parcels from one part of the country to another.

Soon after take off, this flight crew noticed a “minor” problem, which became a major one. It emerged that something had gone wrong with the hydraulic system that raises and lowers the plane’s landing gear—its wheels. That system had worked well enough to bring the landing gear up after takeoff. But error messages created doubt that it would be able to bring them back down again. Eventually the plane would have to land—and when it did, it would do so without tires, wheels, or landing gear. The flight would end with direct metal-on-asphalt contact, the plane’s belly dragging along the runway at around 100 miles per hour.

Who did what: The RealATC video on YouTube matches pilot-controller radio exchanges with a tracking map of where the plane was going. Mainly the exchanges are between “FedEx 1376,” the plane’s crew, and “Chattanooga Departure,” the controller who with extraordinary aplomb handled the flight through most of this emergency.

Why this is interesting: If you have ever wondered exactly how it sounds when people know that lives are at stake, and put their training and procedures into effect, this is an outstanding example. It is like hearing members of a surgical team after an arterial bleed erupts, or a military unit calling for support during an unexpected attack. All these people are doing their jobs very well.

Why this matters: We’ve all heard, and I’ve frequently written, about increasing strain on the aviation system that has led to close-calls and near-disasters. Here is an example of the professional skill—from air crew and controllers—that in tens of thousands of US commercial flights per day has minimized disasters.

Now the video. After it, some notes on the special language they are using, and who is doing what at crucial points. My thanks for our friend Rita O’Connor for her advice on this post.

Viewers’ guide to the video:

Time 0:28: In the first transmission, FedEx 1376 makes its first call to Chattanooga Departure, with the usual formula of its assigned altitude (climbing to 5,000 feet) and direction (“runway heading”—straight ahead after takeoff). Departure responds and clears them for a further climb and to the next waypoint on their route. This is all 100% normal. On the video you’ll also see this course mapped out.

Time 0:50: FedEx reports its first problem—“working a minor issue”—and asks for two shortcuts that will simplify things for them in the cockpit. One is to “maintain runway heading”—just keep going the same direction, without worrying about en route navigation. The other is to stay at 5,000 feet without continuing the climb.

Time 1:10: A message from the Chattanooga Departure controller sets the terms for everything that follows. He tells the pilots that he is about to give them “vectors” — assigned changes in direction — to “keep you in my airspace.” This is a very important real-time intervention. Normally the plane would soon pass to a sequence of other controllers, probably some from “Atlanta Center” and then “Memphis Center.” But this Chattanooga controller is already taking responsibility and keeping himself in the loop, as he remains through the end of this flight.

Time 1:50: A nonchalant-sounding exchange about vectors for the plane, which again is remarkable when you remember the circumstances. At just this moment, the FedEx flight crew is frantically trying to figure out what has gone wrong with their plane. On another radio frequency, which is not part of ATC recordings, they are presumably talking with experts at FedEx about what they should try. As all pilots are trained to do, they are working through their trouble-shooting and emergency checklists. Meanwhile the Chattanooga controller is trying to figure out how to keep the plane clear of mountains, and other aircraft, and within his airspace—while minimizing distractions for the pilots. And all of them, also meanwhile, maintain an all-business, let’s-solve-the-problem tone.

Time 1:55: The controller asks the pilots “do you require assistance”? This is one of two consequential (and by-the-book) phrases you’ll hear in the exchanges. “Require assistance” means, among other things, having fire trucks and other rescue equipment waiting on the runway. The other phrase is “declaring an emergency,” which means that controllers will clear all other traffic out of the way. The FedEx crew initially declines both offers, trying to contain the situation as “normal” for as long as possible. They also say that they’re “talking with company”—with their dispatchers and mechanics at FedEx, on another radio frequency—to get further advice on the situation.

Time 2:30: Chattanooga hasn’t heard from the plane in a while, so he asks how things are doing. The pilots say, for the first time, that they are going to need to come back for a landing rather than proceeding to Memphis—and that it will take a while to figure out the extent of their problems and work through their checklists before landing. Why does this all take so long? Imagine some trouble light coming on in your car—but you’re in a machine whose systems are vastly more complex, and that is thousands of feet up in the sky. The pilots can’t just pull over or press Pause to sort things out.

Time 3:20: The crew again declines an offer to declare an emergency. They say instead that it will take them a while before they set things up for what will be an emergency-style no-wheels landing. Therefore they ask for some delaying loops in the sky, to buy time before they come in for the inevitably rough landing.

Time 4:35: The controller is sticking to strictly-normal discourse, with headings and altitudes and clearances. The flight crew, obviously preoccupied, is giving terse but by-the-book responses. This is the first of multiple times in which the controller issues a “normal” clearance for approach and landing. (The clearance is for the “ILS approach” to Runway 20, which is the same runway plane took off from. “Intercept the localizer” is the standard instruction for aligning with the beam that guides an airplane to the runway.)

About ten seconds later, the FedEx crew breaks off this approach and begins the first of its delaying-circuits around the airport. The next seven or eight minutes are the controller guiding the airplane through these loops, always in an “everything is normal” tone. Each time he gives a clearance for the Runway 20 approach and landing—and then cancels that clearance each time the flight crew requests another loop to buy more time.

Time 6:00: The FedEx crew tells the controller, for the first time, what has been implicit until now: That when they land, they are going to need the fire trucks, because they’ll be coming in without wheels. Listen to the tone on each side. The crew also uses, for the first time, the formulaic language for a plane in trouble. “We’re going to declare an emergency at this time. We’ve got three souls on board, and approximately one and a half hours of fuel.” The fuel report is to let fire-fighters know what kind of fireball they might have to deal with after touchdown. The controller concludes with, “We’ll get the trucks rolling for you.”

The calm through all of this is the remarkable part. From the flight crew who know they themselves will be the “souls on board” for a potentially dangerous landing. And from the controller who is fully aware of his responsibility. In this portion you’ll hear some transmissions from the ground crew and others in Chattanooga, as they prepare for an emergency landing. I assume that this audio has been edited to avoid pauses, and to combine transmissions on different frequencies. I believe that the female voice you hear is from the tower controller at Chattanooga, who relays info to the departure controller and also to the ground crew awaiting the plane when it comes in. The seamlessness of the Chattanooga response is notable.

Time 7:40: The FedEx crew says they are going to do a “low pass” over the airport, to see if by any chance the landing gear have actually come down. They are hoping people on the ground can look up, with binoculars, at the plane’s belly as it comes overhead. The next two minutes of the exchanges are people in Chattanooga preparing to do their best to see. (Spoiler: the wheels stay up.)

Time 12:00: As the plane keeps circling around to figure out its final descent, the flight crew tells the controller that they’re planning a gear-up landing, and that they will “evacuate on the runway.”

Time 14:20: The departure controller tells the FedEx crew “I’ll just keep you on this frequency, sir.” Normally a plane would be switched to the tower controller at this point. The air traffic control team is doing everything they can to eliminate distractions and simplify the pilots’ work load. The departure controller is doing the work by relaying info back and forth between the pilots and everyone else on the ground.

Time 14:40: FedEx requests “another lap,” to try some maneuvers that might shake the landing gear down. These fail.

Time 17:30: The perspective on the YouTube version shifts from a moving map to actual video of the plane’s final descent. The image below is a grainy shot of the instant when the metal of the plane’s fuselage begins scraping along the runway, leaving a trail of spark and flame.

Barely one second after the plane begins skidding down Runway 20, a controller comes on the air to say “Attention all aircraft, Chattanooga Airport is now closed. Airport is closed.”

My admiration to all involved.

And my condolences to the thousands of families grieving this evening.

The focus and calmness of everyone involved was mesmerizing. . Until the folks on the ground said "everyone is watching you." I teared up when they said "everyone." All these people just "doing their jobs," all to bring 3 people home safe. It was an inspiring display of the best humans can be! I cheered a little when they landed. All I know about flying is to keep my seat belt fastened. Overwhelmed with gratitude for all the people who have made every flight I've ever taken uneventful!

I always find these stories intense and often amazing. The crew and the controller are inspiring in their skills and competence.