'Fate is the Hunter'

Watching what people can control, and what they can't. Bad luck prevailed three days ago. And better luck today.

For the past three days, I’ve been thinking again about a book I read back in the 1990s. It is Fate Is the Hunter, by Ernest K. Gann, which was first published in the early 1960s. It is a memoir of Gann’s experience as a military pilot during World War II and as an airline pilot before and after.

Because so few people have first-hand experience in the cockpits of airplanes, a natural instinct would be to dismiss this as “genre” literature.

It is not. I consider it a profound and memorable book. David Mamet, who in addition to his day job as a playwright also flies airplanes, made this point in a column for Flying magazine several years ago. Mamet wrote:

The best aviation writing takes place not in novels, or films, but in the flying magazines. Here, pilots are communicating, in technical language, the drama that took place, finally, within themselves: difficulties, happenstance or error compounded by laziness, fatigue, ignorance or pride; ignorance beaten out through near-averted tragedy; theory triumphing over fear, or excised through practice.

The best book written about aviation is Fate Is the Hunter by the great Ernest Gann. Its contemporary descendants can be found in I Learned About Flying from That, Never Again and the magazine writing of pilots for pilots.

I’ll save for another time why I agree with Mamet about the language of the skies; about the interaction among experience and luck and practice in this fundamentally perilous pursuit; about “ignorance beaten out through near-averted tragedy”; and about the value of the flying magazines. I subscribe to half a dozen of them and read them as soon as they arrive. Some people have “to-read” stacks of various high-end publications. I have “carefully read and noted” stacks of COPA Pilot, AOPA Pilot, Flying, IFR, and so on.

But Gann has been on my mind because of a tragedy three days ago. That was a small-airplane crash on Thursday afternoon in New Jersey, which killed not just a well-known flight instructor and aviation figure, Thomas Fischer, but also Glen de Vries. Before 2021, de Vries had been recognized in the tech industry as an entrepreneur and innovator. But only a month before the crash, he had become known world-wide as one of the astronauts aboard the same “Blue Origin” flight on which William Shatner went (briefly) into space.

I had been planning to write about the balance between the knowable and the unforeseeable when it comes to aviation safety. (The exact causes of this New Jersey crash are still not known.) And about the difference between how the airlines work and how non-airline “general aviation” does. And about the similarities, and the differences, between the risks we all assume when getting into a car, and those that begin the moment you push in the throttle in an airplane and are committed to a take-off.

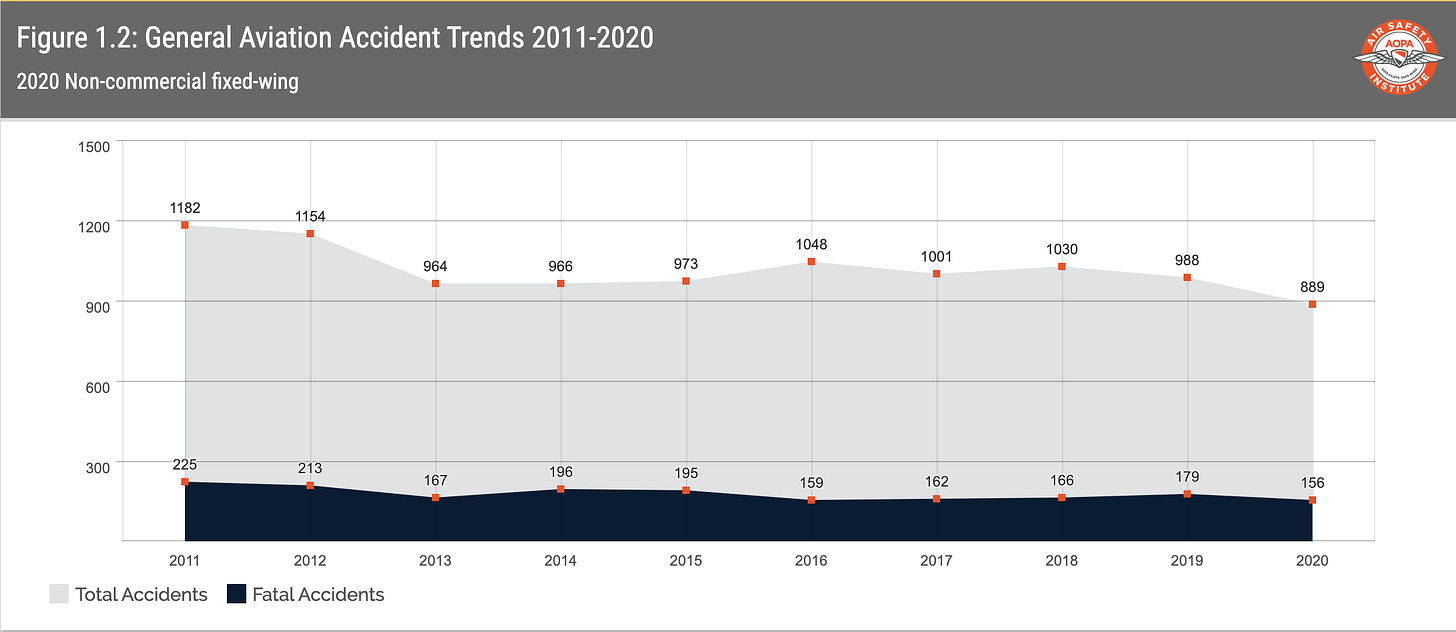

For now I’ll just point you toward the canonical source on all questions of safety in general aviation, the “Nall Report” from AOPA Air Safety Institute. Here is a sample of the overall trend. What it shows, in brief, is that across the country there are an average of two-plus “accidents” per days in non-airline aviation. And on average, one person dies every-other-day in these incidents. (For comparison, about 100 people die every day in car crashes in the US, but of course there are many more drivers than pilots.)

A few hours ago as I write, I witnessed one of these “non-fatal accidents.”

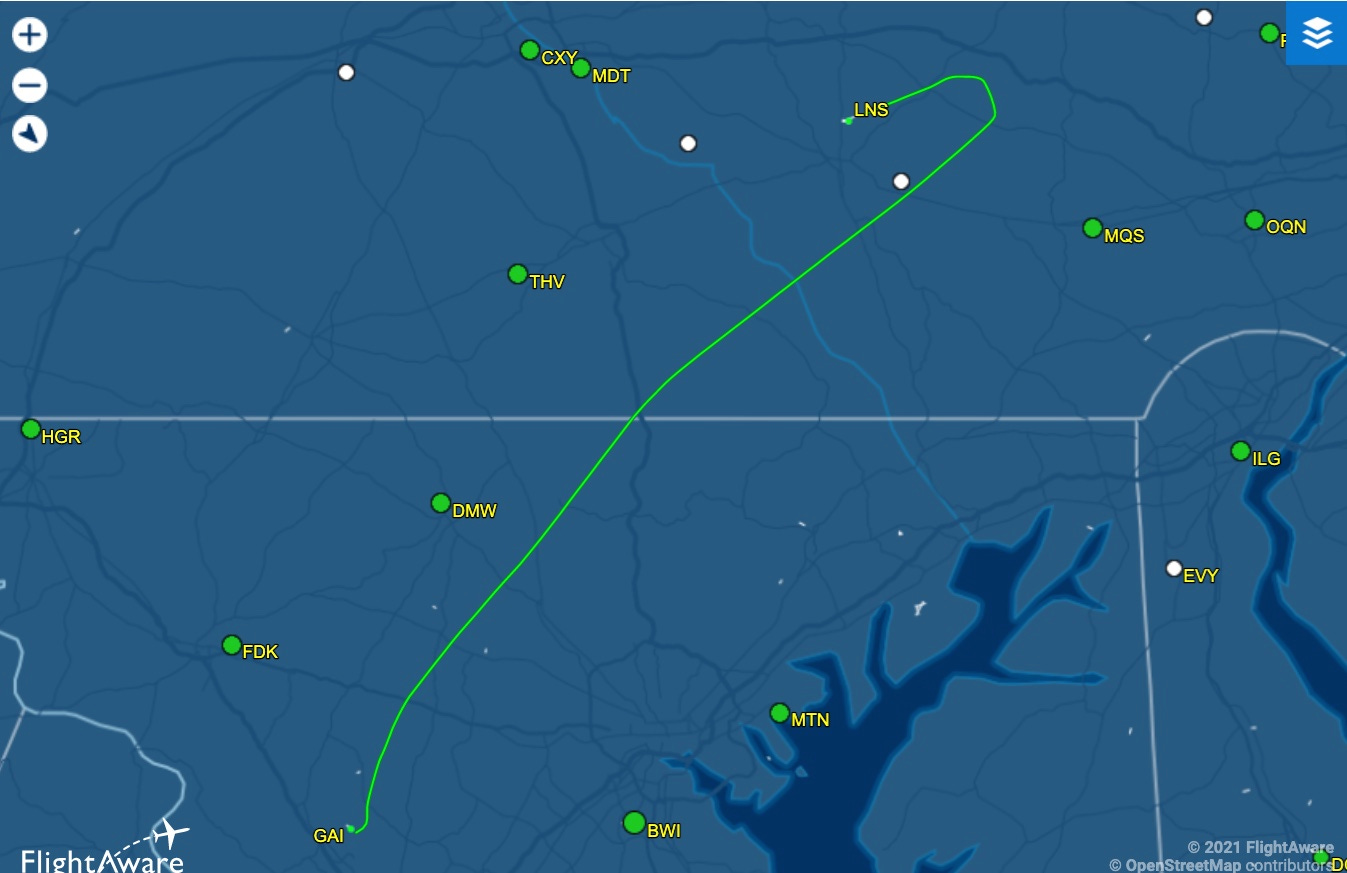

I’d gone out this afternoon for a training flight, with “practice approaches” to tune up my muscle-memory of the plane’s avionics. The outbound leg was from Gaithersburg, Maryland, where our airplane is based, to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

(For aviation friends, in the acronym-dense prescribed lingo of the business: it was a practice approach, in VFR conditions, to the RNAV Runway 26 LPV approach at KLNS, to a full-stop landing. I was talking with Harrisburg Approach until I turned inbound on the approach, and soon switched to Lancaster Tower. I’ll say more these abbreviations, and why they’re useful, some other time.)

Here is this afternoon’s track from FlightAware:

On the way back, I returned straight to Gaithersburg.

I landed, was tying down the plane, and then saw something unusual on Runway 14.

I didn’t notice the instant this plane touched down, five or six back in the landing queue after me. It was an extremely busy afternoon at Gaithersburg (which has no control tower, but which is a very active training site). Planes were landing in rapid succession.

But as I was about to leave my plane, after tying it down and locking it up, sudden movement caught my eye. I looked up and could see that it was an aircraft beginning to cartwheel down the same runway I had just landed on. And then thick smoke started to come from its engine.

Like everyone else at the airport at that moment, I began running toward the plane. I dropped my bags and gear and ran.

The most important news is: the two people aboard the plane were both unhurt. They seemed devastated, when I spoke with them later. But as always in aviation, you can imagine things being worse.

The other planes that were “in the pattern” and about to land had to suddenly go somewhere else. Frederick, Maryland? Leesburg or Manassas, Virginia? Martinsburg, West Virginia? I don’t know—just, some other place. They couldn’t land here.

The same for the many planes that had been preparing to take off, and had to go back to their tie-down areas and let out their passengers. This runway was closed, until the FAA could check out the plane and any damage to the runway—and because this is the only runway at the airport, the whole airport was closed as well. (Update: it reopened long after dark last night.) The airport authorities asked everyone who had been around for the incident to stay and give a statement, including me.

Why do I connect this with Ernest K. Gann? Because his memorable book described the things that practice and prudence could prevent, and those they couldn’t.

I spoke briefly with the plane’s pilot, who said that just as the plane touched down, the landing gear—its wheels—suddenly collapsed. Everything after that was beyond his control. In the photos you can see the tires as the black circles oddly pushed up to window-level of the cockpit. Investigators will look into this whole sequence. But in a case like that, no planning or practice would matter. Fate would take over.

This is the only such landing incident I have witnessed through 2,000-plus landings of my own. I am of course glad that no one was hurt in this episode, and sorry that two people died in the still-to-be-understood tragedy three days ago. We all live in the now.

Fate is the hunter.

I would have wanted to know how many accidents and how many deaths per flight. In the mid-'90s, when I still lived in DC, you could get a half an hour flight with an instructor for a nominal fee. I took my niece a handful of times, the first when she was 7, and we'd each get to fly. She did so well the first time the instructor gave her an extra take off and landing.

When I took her, I assumed that with an instructor, this activity was VERY safe, in large part because it's hard to find anything to crash into in the sky. Caution genes run in my family. My parents got seat belts in the '57 Chevy in 1960 or '61, we had the first Peugeot wagon in France with rear shoulder belts, as my father showed the men at the factory how to install them (a simple topological problem) and I got Bell hard-shelled helmet serial # 7022 back when you had to mail order them.

I'm still guessing that our flights were quite safe, but I'm wondering just a little.