Eloquence is Overrated

Don't remember lines from a speech? That could be a sign of its success.

Sometimes memorable lines accompany memorable messages. The greatest example in American presidential rhetoric will always be Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address:

Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.

Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword…

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in…

The closest comparison in presidential rhetoric of the past century—a memorable phrase, conveying an important idea—is probably Franklin Roosevelt, with the first paragraph of his First Inaugural address:

“The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.” (Starting at time 1:07 of the PBS clip below.)

On a one-liner basis, Ronald Reagan matched phrase-making with meaning when saying in 1987 in Berlin, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.”

The perils of ‘fine writing’

You can think of other cases. But the point of these exceptional examples is that they are exceptions.

Usually “fine writing” in speeches comes across as decoration—extra icing on the cake. For instance: one of Richard Nixon’s trademark phrases during his 1968 presidential campaign, re-used in some pre-Watergate presidential addresses, was “the lift of a driving dream.” “A driving dream? It sounded like an automobile commercial,” the great Russell Baker wrote in his New York Times column.

Even John F. Kennedy had a weakness for phrases that called attention to their own fanciness. Eg; “Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.” For many more examples, see The Kennedy Promise, published in 1974, an acerbic book by the gifted-and-ever-acerbic late British journalist Henry Fairlie.

And the presidential lines that do stick in the memory are often unfortunate—for instance, “the era of big government is over,” from Bill Clinton, and either “mission accomplished!” or “axis of evil” from George W. Bush. Going further back, “the war to end all wars,” from Woodrow Wilson. Or, “I’m not a crook,” from Nixon, the year before he resigned.

Eloquence on the ‘macro scale’

Meanwhile some of the most important political speeches lack obvious applause lines. The three words that may be most remembered from Dwight Eisenhower’s eight years as president come from his farewell address, just before turning the White House over to Kennedy in 1961.

Those words were “military-industrial complex,” shorthand for Eisenhower’s powerful warning against the perils of a corporate-profit-generating, permanently militarized state. (For fascinating backstory on that speech, see this piece by Jim Newton, from The New Yorker in 2010 For today’s much larger military-industrial complex, see this “Chickenhawk Nation” piece by me, in The Atlantic six years ago.)

I once went in detail into what I consider Barack Obama’s finest rhetorical performance—his “Amazing Grace” speech to mourn the Black pastor and worshippers gunned down at the Mother Emanuel church in Charleston, South Carolina. My point was that a spellbinding presentation contained barely any quotable standalone lines. I hope you recall that speech; I bet you cannot recite its phrases.

In another Atlantic analysis of an earlier Obama speech, I tried to explain the different varieties of “eloquence” that presidential rhetoric could embody. Inevitably this also includes references to Kennedy and Lincoln.

Friends and foes alike recognize that oratory has played an unusually large part in [Obama’s] political ascent. It is beyond question that one 17-minute speech put him on the national map—his debut address at the Democratic Convention in Boston in 2004….

But Obama's eloquence exists almost exclusively on the macro scale—the overall impression he gives of the subject he is wrestling with, and of his own temperament and cast of mind. You could take John Kennedy as the opposite extreme; his speeches are far more memorable, and quotable, for epigrammatic phrases than for their more elaborated thoughts.

Abraham Lincoln may be the one example in our public life of success at both levels. His first and second inaugural addresses, plus the Gettysburg Address, are considered in a class of their own because they combine lasting beauty of phrasing—"malice toward none," "mystic chords of memory," "government of the people, by the people, for the people," "every drop of blood drawn by the lash”—with depth of thought.

Language that is clear as glass

Content, that is, can be independent of form. And effective orators sometimes succeed by making their language practically invisible. For them it serves as a pane, allowing the undistorted meaning to shine through.

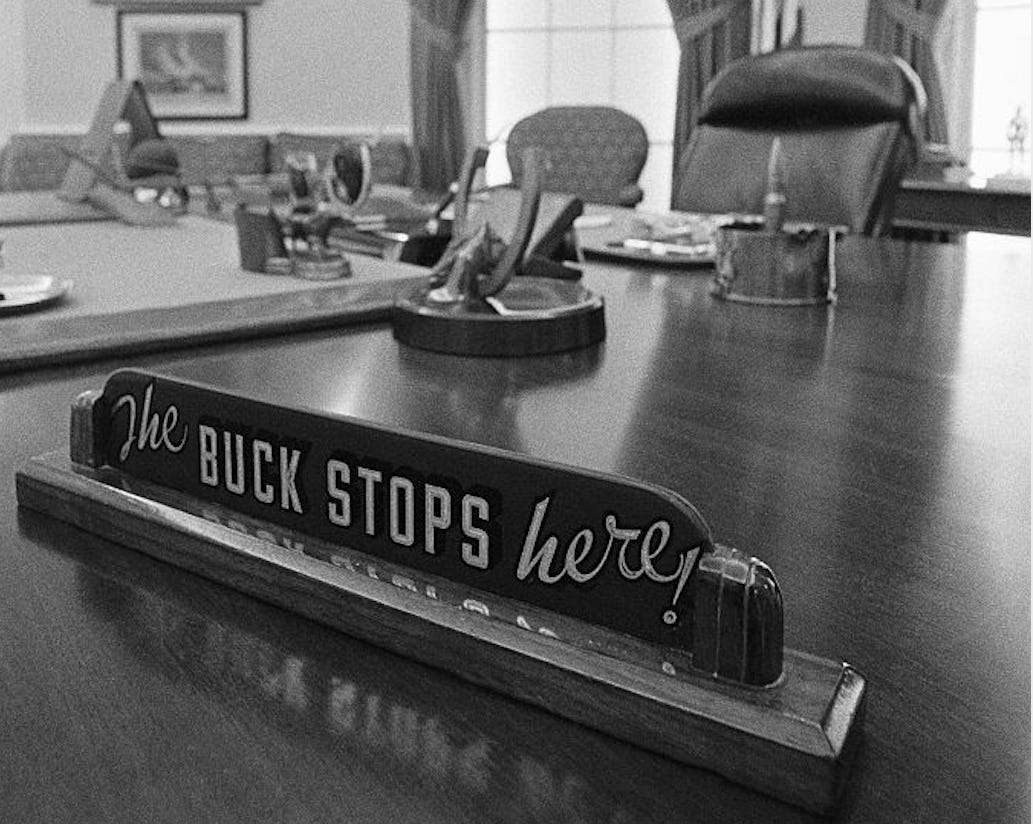

Take Harry Truman as a 20th century example. Practically no one can quote a turn of phrase from any of his speeches. The exceptions illustrating the rule are the famous sign on his White House desk, “The Buck Stops Here,” and his 1948 campaign rhetoric about the Republican-controlled “Do-nothing Congress.”

But anyone could listen through Truman’s plain-spoken phrasing to know what he meant—about the end of World War II, about the beginning of the Cold War, about the launch of the Marshall Plan.

Consider, for one dramatic example, the stunning matter-of-factness in Truman’s statements about his decision to drop the first atomic bomb ever used, on the people and structures of Hiroshima. He began his address to the world this way:

Sixteen hours ago an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base.

That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T.

It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British "Grand Slam" which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.

The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.

And, gruesomely, later on in the speech:

It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East…

We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications.Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war.

I’ve never heard anyone quote this speech. But no one could mistake its meaning, then or now.

The plain-spoken tradition, these days

Joe Biden’s speech this past Tuesday night, August 31, also reflected the power of simple plain-spokenness. Barely three days after its delivery, I defy anyone to recall poetic passages from it. But, as with Eisenhower and Truman, its message was unmistakable.

The opening of Biden’s statement was an unadorned as any speech could be:

Last night in Kabul, the United States ended 20 years of war in Afghanistan. The longest war in American history.

We completed one of the biggest airlifts in history with more than 120,000 people evacuated to safety. That number is more than double what most experts thought was possible. No nation, no nation has ever done anything like it in all of history.

Only the United States had the capacity and the will and ability to do it.

And we did it today.

“And we did it today.” The line was delivered as plainly as it was written, which in the circumstances made it all the more effective.

The rest of the speech was built around direct, declarative statements:

“In April, I made the decision to end this war.” I made the decision.

“I was not going to extend this forever war. And I was not going to extend a forever exit.”

“I take responsibility for the decision.” The buck stops here.

“The bottom line is: There is no evacuation from the end of a war that you can run without the kinds of complexities, challenges, and threats we faced.

”None.”

None was written, and delivered, as a thought on its own.

William Jennings Bryan will be remembered, among other things, for his “cross of gold” address. Theodore Roosevelt, among many many other things, for his “man in the arena” speech.

All leaders are remembered—for better, for worse, if at all—mostly for the choices they make and the consequences they accept. But in democratic societies they must offer explanations for those choices. If they’re wise, they strive toward the kind of eloquence that rings true for them.

The Joe Biden of the young hotshot era could sometimes try too hard, and end up sounding inauthentically like “a Kennedy,” or worse.

At this stage of his life and career, Biden is offering eloquence of a minimalist, authentic-seeming, Trumanesque style.

A different, purely personal note: In the spring of every year, I publicly note the birthdate, in 1925, of my late father, James A. Fallows. And on September 3, I note the birthdate in 1927 of my late mother, Jean Mackenzie Fallows. On this September third, my siblings Sue, Tom, and Katie join me in gratitude for the parents we had, and for the love and hope they brought into so many people’s lives.

Jim -- I always thought that Truman's most memorable comment were his words to reporters after taking office: "When they told me yesterday what had happened, I felt like the moon, the stars and all the planets had fallen on me."

Even in the loftiest realms of literature, examples of clear, plain-spoken, language have profound effect.

What is the central theme of King Lear? Lear states it himself:

“Who is it that can tell me who I am?”

…

Or later, as begins to find his way again:

"I am a very foolish fond old man,

Fourscore and upward, not an hour more nor less;

And, to deal plainly,

I fear I am not in my perfect mind."

The sad news that Nanci Griffith, poet and musician, had died recently reminded me of the opening lines of her signature song, “Love at the Five-and-Dime”:

"Rita was sixteen years

Hazel eyes and chestnut hair

She made the Woolworth counter shine"

A fully formed character created with 15 simple words. And what follows is a complete tale of two lives distilled in some 200 plain-spoken words (not counting repetition of the chorus).