Election Countdown, 65 Days to Go: The New ‘Accountability’ Problem.

Remember when a picture was worth a thousand words? Now a viral tweet or TikTok clip can outweigh whatever else is said about a candidate. Some new examples, and what the press can (and must) do.

Kamala Harris and Tim Walz getting off the campaign bus in Pennsylvania this week. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.)

This post is about a media problem that I’ve noticed more and more as the election draws closer. It’s an “accountability” mismatch. Namely:

As certain parts of the press have become more and more significant in shaping attitudes and opinions, they have become less and less “transparent” about their decisions, and less and less accountable for what they do.

The result is bad for the mechanics of democracy in the short run. And in the long run it is more dangerous for the press than many of its leaders seem ready to recognize.

Now let’s step back and take this in order, with six steps.

1) Since the dawn of time: A picture is worth a thousand words, and emotion has always outweighed cold ‘logic.’

We didn’t need the era of newspapers to tell us that people are emotional more than rational creatures. Through its few centuries the newspaper era has reinforced how people could be swayed by the few words in a headline more than the hundreds of words in a story: “Headless Body in Topless Bar,” the greatest moment in the New York Post’s existence. “Dewey Defeats Truman” for the Chicago Tribune, the most memorable and most embarrassingly wrong banner headline in their long history. “Harvard Beats Yale, 29-29” for the Harvard Crimson.

In the more than 150 years since photo-journalism became practical, we’ve also come to expect the narrative and “argumentative” power of photos. The Hindenburg explosion, which would be forgotten now save for a real-time photograph. The photogenic Charles Lindbergh’s arrival in Paris, which made him a world hero. The unforgettable 1972 wartime photo by Nick Ut of Vietnamese children running in terror from a napalm attack. “Tank Man” at Tiananmen Square in 1989. The airplanes hitting the World Trade Center in 2001. The Obama team in the Situation Room watching the operation that killed Osama bin Laden. Many more.

So we’ve assumed, as a starting point, that headlines might affect us more than long essays from reporters and editorialists, and that photographs might magnify that impact. And now we have many more cues—sub-headlines (known in the business as “deks”), tweets and TikToks "(“social sells”), page placement whether in print or online—and other “framing” signals that together give us an idea of what developments are really “news” and deserve attention.

2) In recent times, the power of the ‘social sell.’

What’s different now, I’ve come to think, is a scale difference, working in opposite ways.

—The impact of a full array of social media—tweets, shares, TikTok and YouTube clips, and so on—that reaches more of the range of human psyche and population than previous media have, with bigger effect. This is a step up in scale of impact. But meanwhile…

—The transparency and accountability of this part of the media ecosystem is lower than it ever has been. I know who wrote a newspaper story or radio or podcast segment. That is because I see their names on the article or hear their voices. But I have no idea who decided how to lay out a publication’s front page, online or in print, or to “sell” stories online in ways that cement their impact.

Josh Marshall of TPM has a very good recent Xitter thread on this reality. Among its implied points is the weird “sandwich” challenge of knowing whose judgments shape the news. At the delivery end, we see reporters’ bylines on their articles, their faces on news casts or discussion shows, their voices on podcasts or the radio. At the top end, we know who owns the media companies, and who the top editors are.

But in between? The metaphorical meat in the sandwich? The people choosing what stories to put on a print or online front page? Which headlines to give them? Which stories to follow, and which to let slide?

We have no idea who those people are. Or what standards they are using. Or what effects or criticism or “A/B online tests” they might respond to. Or where the think they’ve done best, and worst. They’ve become the most influential, and least transparent or accountable, part of our information ecosystem.

3) Why this comes up now: Kamala Harris ‘evading’ questions.

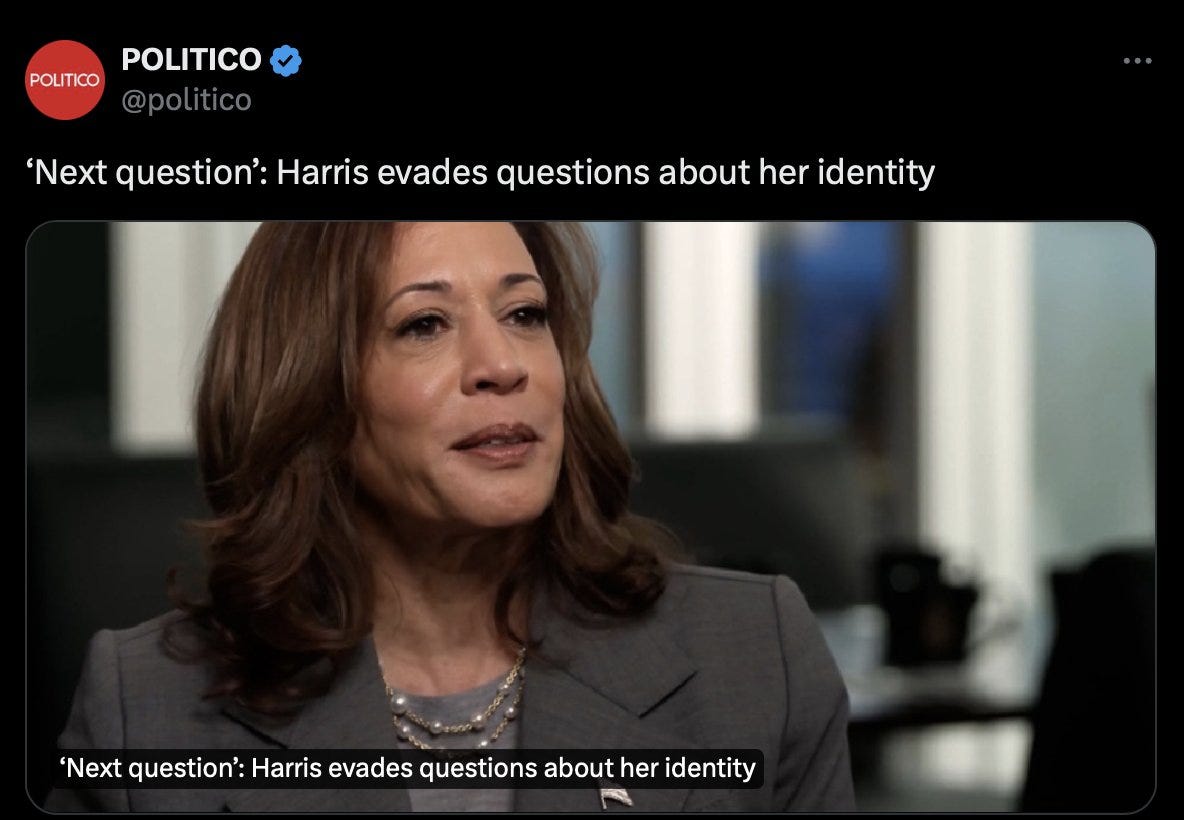

This past week Politico put out a tweet that is arguably the worst and most misleading way a story has ever been presented. It is the one you see below.

As background: During her CNN interview this week by Dana Bash, with Tim Walz, Kamala Harris wisely refused to take the bait of replying to Donald Trump’s racist “She just turned Black!” challenges. “Next question” was just the right response.

That is more or less what the Politico article itself also said. (Ie: That Harris doesn’t need to trumpet her role as potentially the first Black female president, since her identity is apparent each time she takes the stage.) But that is not what the egregious headline suggested. If you saw only the headline and tweet, which is all that most people would ever know about the story, you’d think it was one more illustration of Harris being “evasive.” Just another slippery politician.

A day later, Politico quietly removed that tweet, and changed the headline to something more anodyne. But by then the damage had been done—to Harris, and to Politico, in different ways. And by then Josh Marshall had written his explanation of why the initial impression from that tweet is the one that would matter. It was chosen (and then removed) by people not named, for reasons not explained.

4) More illustrations of framing and ‘sells’ that matter, and whose origins no one feels obliged to explain.

Let’s start with a dual image, of New York Times front pages. The images are originals, from the NYT site. The highlighting in red is by me.

On the left, a now infamous front page just before the 2016 Trump-Clinton election, with what you’d have to call blowout coverage of a James Comey intrusion in the election.1

On the right, you see not the top but the very bottom of a front page this past week. You’d need a magnifying glass to make it out in real life, but the little red box is the Times’s three-line intro of news that another Federal grand jury had re-indicted Trump for trying to overthrow the 2020 election.

Legally, politically, objectively, any reasonable person would say that these stories were of comparable importance, to say the least. But see if you can detect any subtle difference in the way they are “sold” and played.2

Perhaps someone could make a logic-and-news-based argument for presenting the two stories in such different ways. The problem is that no one at the Times even deigns to make the case. Back when there was a Public Editor, that person had official standing to go around and ask, in essence, “Hey, wtf?” Now, decisions of this sort are unexplained and ex cathedra.

Same goes for why the paper (and other leading media) have not followed up on last month’s WaPo scoop about a $10 million payoff from Egypt to Trump. Why none of them has committed resources to investigations of “Trump’s cognitive fitness for office,” while all of them did so about Biden. Why there is no followup on Trump’s hallucinatory claim of his helicopter flight with Willie Brown. Why there was extended blanket coverage of Russian-hacked emails from Hillary Clinton’s campaign, but none about Iranian-hacked emails from Trump’s. Why there is no press demand for medical data or records on what happened to Trump’s ear during the shooting in Butler, Pa.

Maybe there’s an explanation for this difference in emphasis and “framing.” It would help to hear it from someone in charge.

5) The sell for a ‘Gotcha!’ story, that has no ‘got.’

Here’s another sample, as it happens also from the Times. It was a hugely splashed story this morning about the first-term governor of Maryland, Wes Moore.