Don't Get Covid.

Guidance, anecdata, and news you might be able to use from our household. Also: do get vaccines.

This post is about my own medical experience, a topic I generally avoid.

A few years ago I made an exception in writing about a potentially serious disease I’d once had, which affects many people but is barely known and rarely discussed. This is parathyroid disease, or hyperparathyroidism, the disorder from which the comedian Garry Shandling died six years ago.

This was a condition I had simply never heard of before I was diagnosed with it some 15 years ago. It is seriously damaging and is virtually incurable without surgery. But for most people (including me) it can be fully resolved through an operation—which I got in 2009 from a highly skilled team at UCSF headed by Dr. Quan Duh.

I told my story because I thought it might help if more people were aware of the symptoms, prevalence, and significance of this disease. Since then I have heard from a steady stream of readers who said that knowing about it had indeed helped them.

In the same “it might help you to hear about this” spirit, I’ll write now about some of what I’ve recently learned, or at least experienced, about “long Covid.”

Everything about this Covid era is a combination of data, conjecture, larger patterns, and individual exceptions. Everyone involved—from research scientists to medical practitioners, from public officials to individuals and families—is constantly and unavoidably recalibrating plans, assumptions, and behavior as new information arrives.

As part of that process of trying to understand a still-mysterious, rapidly shifting phenomenon, here is my own recent anecdata about Covid. I share it because the experience contained surprises for me, and perhaps it will be useful to someone else.

The road to Covid.

Here are some relevant points about my Covid background.

I have been early, active, aggressive, and persistent in taking preventive measures. Even before anyone had heard of “long Covid,” I wanted to avoid getting sick.

Deb and I did everything we could to get vaccines as soon as they were available. We’ve had all the boosters at each stage since then. We spent much of the first pandemic year by ourselves at home. When we started taking (a few) airline trips last year, we wore the white, full-strength N95 masks. We have used black KN95 masks in public gatherings and in stores.

We’ve tested very frequently. Deb has never tested positive. Nor—thank God!—has her mother, Angie Zerad, in robust physical and mental health as she nears age 101.

It’s also relevant to point out that I’ve always been “healthy.” The parathyroid issue mentioned above is my only encounter with a hospital since I got my tonsils out as a child. Most annual-physical visits to my doctor end with him saying, “Everything looks fine, see you in a year.”

I had always tested negative for Covid—until I didn’t, after a college reunion this past June. That reunion had been postponed from the two previous summers, out of Covid concerns. This year’s version was carefully run, and most people, including me, wore masks most of the time. But it included a few indoor social gatherings, where people took off masks to eat, drink, and talk. Am I glad I went to the reunion? Yes. Should I have kept a mask on the entire time, and not mingled with other people over drinks? It’s harder to say.

I was annoyed to become infected, mainly because of the time-sink and inconvenience it involved. But in my 12-day run of testing positive (and being isolated) in June, Covid as I experienced it was a nuisance but not a “problem.”

I had a cough for a few days. I stayed in a separate part of the house. I didn’t take Paxlovid—this was after “Paxlovid rebound” cases were being reported, and the excellent and trusted nurse-practitioner at our medical practice said (in a Zoom call) that unless my symptoms got worse I should steer clear. Less than two weeks after it started, the whole thing seemed over. Again, thanks to vaccination, “risk of death” didn’t cross my mind.

That was three-plus months ago; I’ve tested very frequently since then, especially before any meeting or event; and I’ve never tested positive since late June.1

How we feel, when we feel ‘bad.’

But starting about six weeks ago, I was aware of feeling just … bad. This is the time to bring up another relevant background point, which is that the most robust part of my inevitably aging body has been its cardiovascular system.

I grew up in a small-town-doctor’s family where the watchword on personal illness was “most things get better on their own.” The advice was sometimes shortened to “tincture of time.” This applied even when I broke my leg on a playground as a kid but waited two days before my dad thought it was worth getting X-rays. We four Fallows children had the world’s best parents, and among his patients, our dad was a renowned and beloved diagnostician, as I detailed after his death. But they didn’t want us to be hypochondriacs.

Since my teenaged years I’ve done regular aerobic exercise. I’ve run marathons, nearing a 3-hour time. (3:01 at my best.) I use a rowing machine several times a week. My resting pulse rate has always been low. My lung capacity has always been high.

Because of all this I was hyper aware, starting recently, that the very area where I’d always felt strongest was where I was feeling … “bad.” My heart rate was higher than usual. I was breathing hard, rather than easily, when going up the three flights of stairs in our house that I have leapt up two-steps-at-a-time since forever.

Odd other things popped up. The finger-tips on one hand started tingling. My tongue hurt. Deb remarked that I looked “pale.” I slept even worse than usual.

Through these same recent weeks Deb and I were in a nonstop blur of airline travel, multiple time-zone changes, big public events and performances, and overall stress. Almost every day I was giving a speech, writing an article, emceeing an event, doing a podcast, making a deal. So I put all this in the “shake it off” / “let’s catch up when we get home” category.

But in the week or two before we got home, I found myself telling Deb, in just these words, “I don’t feel good.” So the first thing I did on return to D.C. was to see, in person, our excellent nurse-practitioner. Then these random complaints took on tentative shape.

Who knows what ‘long Covid’ means?

To skip ahead in the story, all the complaints I’d had, even the finger-tingling, appeared to fit one of the ever-emerging, still-not-understood patterns of Covid after-effects. I don’t know whether to call this “long Covid,” or whether it has any bearing to Covid at all.

My dad always resisted talking with patients about the names for any problem they might have. In discussions with them he preferred to concentrate on specific symptoms and how to deal with them. “You’re having some shortness of breath, so let’s try…” Giving a name puts people in a different frame of mind. And the whole “long Covid” concept is so fluid and undefined that, for individuals, the alarm-value of the term probably exceeds any therapeutic benefit.

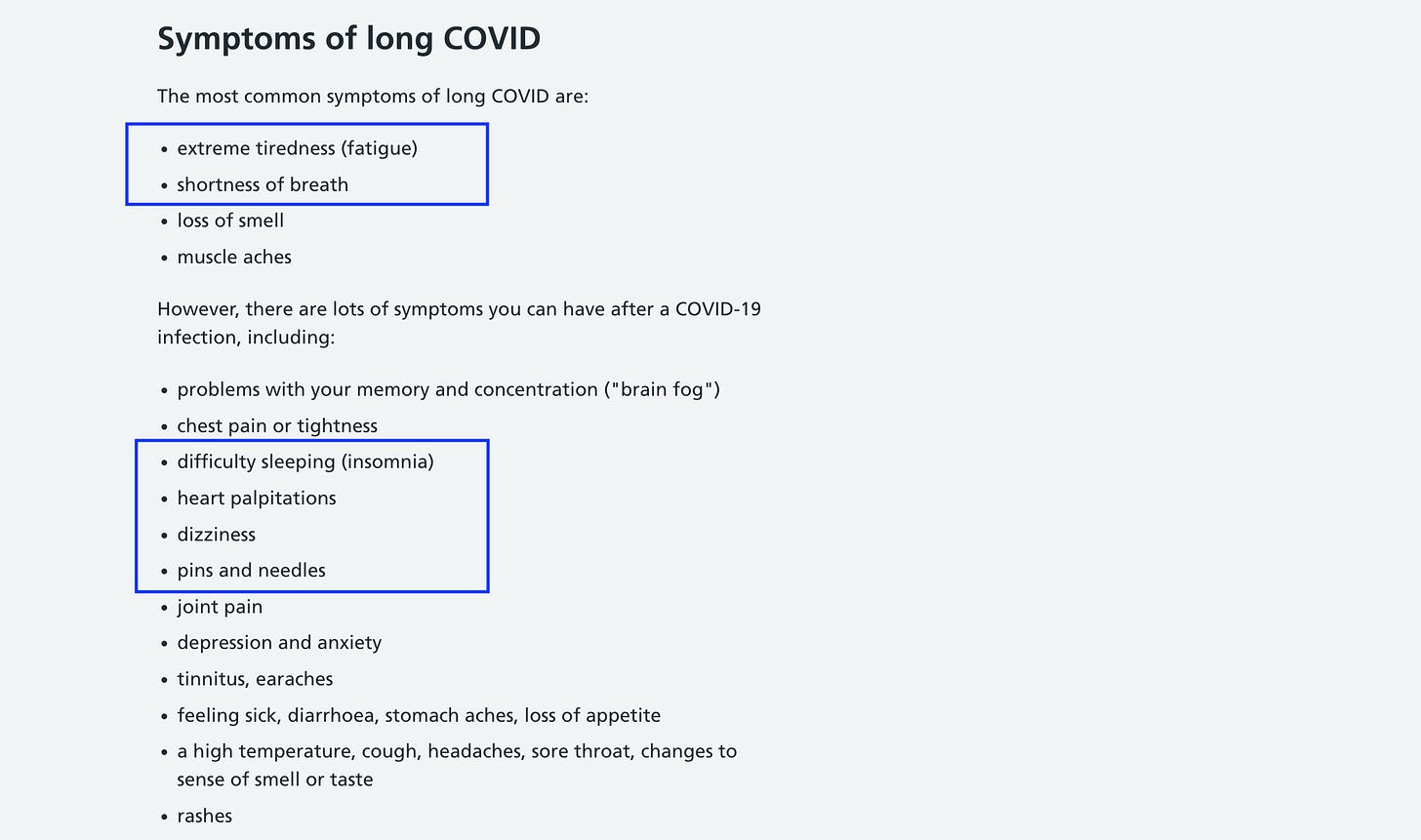

So I’ll just describe a set of symptoms that I hadn’t noticed before my seemingly mild Covid encounter, but that I’ve noticed since. The list below, which does use the “long Covid” name, is from the National Health Service in the UK. What I noticed is that I don’t have anywhere near all the problems they itemize. But every problem I did have, shown in highlights, is on their list. (I never had the taste/smell issues, or others they include.)

Now comes the interesting twist, and the main point I hope might be useful to others. It involves a particular vitamin, and its role in the syndrome mentioned above.

Was vitamin B12 the answer?

After hearing my symptoms, our nurse-practitioner ordered a range of tests, including a blood reading that is not part of the routine lab panel. This was for the level of vitamin B12 in my system.

As it happened, the test showed a low B12 level. And as it also happens, in the ever-expanding realm of what’s known or guessed about Covid effects, one possibility involves B12 absorption. My layman’s understanding of the possible connection is this:

-Covid can impede the body’s ability to absorb or metabolize B12, which in any case decreases with age.2 After a few weeks, the body starts running low on its existing B12 stores. Then you can start showing symptoms of B12 deficiency—which are similar to those on the chart above, and cover everything I had been complaining about.

Is this what happened to me? I can’t know, and don’t pretend to. As a doctor friend has pointed out, the evidence for a B12/Covid connection is quite limited. In my case, maybe it’s just been a hard spell of travel. Or coincidence. I don’t know.

I do know that I have been taking supplementary B12 for a week and … I feel better. (On the other hand, in this same week I haven’t been on airliners and at endless meetings.) Deb says I look less pale. My heart rate seems to be back at its usual level. I’ve been doing normal exercise again. Weirdly, the finger-tip tingling has gone away.

Would I like this change to be real and lasting? Obviously. Do I know enough to be sure —or know for certain about the underlying cause? Obviously not.

My nurse-practitioner has sensibly ordered a range of other tests, still to come. And I am aware of a caution I just received from a friend who is a renowned Covid expert:

There’s some danger, in a vague disease with several possible causative pathways (persistent viral reservoir, immune dysregulation, etc) that lots of people will get lots of treatments (Paxlovid, steroids, [JF—I’d add B12]) and some will feel better – possibly coincidence, possible placebo effect, and possibly real. This is why we do clinical trials.

I agree.

But the whole situation is “different” enough from what I’d expected to seem worth mentioning. It was “different” in the emergence of possibly Covid-related symptoms, long after my mild Covid case had gone away. It was “different” in the possible role of one household vitamin—in symptoms, and in their relief.

If this helps you, please add it to your range of data from our era. And please be sure you are up to date on vaccines. And support increased clinical tests. And realize that if you still have a chance to avoid getting Covid, you’d rather not get it.

In the aviation world, a long-time source of important info has been PIREPS. These are Pilot Reports, information passed by pilots to air traffic controllers about what they are experiencing along their journeys: Winds, cloud levels, turbulence, smoke from fires, icing levels, bird sightings.

No other flight might encounter the same flock of birds you saw; the winds or clouds might have shifted when the next plane comes through. But the idea is that more information gives everyone a better picture. There’s always a chance that your PIREP will make a difference in helping other pilots complete their journey safely.

Think of this as a PIREP for the journey we’re all making through the Covid era. Or a PAREP, for Patient Report, if you prefer.

Either way, I hope the information will be of use.

I am talking here about the “rapid result” home-use antigen tests, indicating whether you could potentially infect others. They’ve all been negative. I resumed doing the PCR tests, offered by the D.C. government in its excellent library-based program, two months after my own infection ended. (Closer to an infection than that, they would have been predictably positive.) They have been negative every time since then.

From the non-peer-reviewed journal article cited above:

“SARS-CoV-2 could interfere with vitamin B12 metabolism, thus impairing intestinal microbial proliferation. Given that, it is plausible that symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency are close to COVID-19 infection… In addition, B12 deficiency can result in disorders of the respiratory, gastrointestinal and central nervous systems. Surprisingly, a recent study showed that methylcobalamin [a form of B12] supplements have the potential to reduce COVID-19-related organ damage and symptoms.”

Jim, I am sorry to hear that you're dealing with this, but I will respectfully suggest that you put the wrong headline on this one. We're all going to get COVID--it's endemic now. Saying "Don't get COVID" is, at this point in the pandemic, equivalent to saying, "Never move on." It's telling people to keep living in fear, on some level. Because as far as I know, not a single scientist has ever said it's going away. We will never eradicate it. Like the flu, it will be with us forever, and hopefully when we get it, it won't be too bad. Headlines like this, to my mind, contribute to an overly fearful approach to life where (as I sometimes see in the DC area) people mask outside and, even more incredibly, mask their *kids* outside. Masking is in general bad for society, and--like the vaccines--doesn't stop you from getting COVID. (I would suspect that almost everyone you know who's had COVID has been vaccinated and worn a mask a lot.) Masking is also really bad for kids, for a whole host of reasons that have been pretty well documented. And, of course, there's the recent Harvard study suggesting that some cases of "long COVID" may be a function more of psychology than physiology (not that I am saying that's true of you): https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2022/09/depression-anxiety-may-escalate-chances-of-long-covid-says-study/. Anyway, those are my thoughts. If we were still at U.S. News, I might suggest a headline that reads, "Long COVID Stinks--Here's My Experience." Hope the B-12 works and you feel better soon!

All very familiar----After my wife and I were "early adaptors" becoming infected in January 2020 while working in Singapore / Malaysia, which was honestly horrible (coughing so long and hard that I developed three separate hernias, I lost my voice for about 3 weeks, also lost about 18 pounds, and generally felt horrible for about 6 weeks---my doctors told me that I probably was able to continue breathing only because of taking significant amounts of prednisone that I always keep on hand for asthma emergencies); we both suffered a second more recent bout (despite full vaccines and boosters) that was much less severe, and my wife and I both have much faster pulse rates and about half the lung capacity we had prior to first infection----huffing and puffing from only minor activities. This seems to now be our new normal, much weaker and less healthy for more than 2 1/2 years. We realize we are lucky, and feel thankful that we are still among the living, albeit with half the strength and energy we had prior to COVID. We just had our third booster and hope these long COVID symptoms will not get worse, but who knows.......